Three Quarters of Magnitude

Plus: This Week's Featured Place: Detroit, Michigan, The Rise, The Fall, The Attempted Revival

Inside this Issue:

Quarters of Magnitude: Fed Dials Rates Up with Three-Quarter Jump

Muskerade: A History of Tesla’s Turbulent Rise

A New Era? A Four-Decade Trend Comes to an End. Maybe

Up In Claims: What to Do About Sunshine State’s Insurance Rates

Ivy Leaks: College Endowments and Offshore Tax Havens

Pension Apprehension: Economists Discuss Fiscal Future of Social Security

And This Week’s Featured City: Detroit, Michigan, The Rise, The Fall, The Attempted Revival

Quote of the Week

“If you want to get inflation under control, while minimizing the impact on growth, what you need to do is get Saudi Arabia to increase oil production, get Russia to allow wheat out of Ukraine and get Taiwan to produce more semiconductors so we can get auto production back online. And the last time I checked, chair Powell, powerful though he is, doesn’t have instruments to do any of these things.”

-Bloomberg’s Tom Orlik, speaking on the Bloomberg Stephanomics podcast

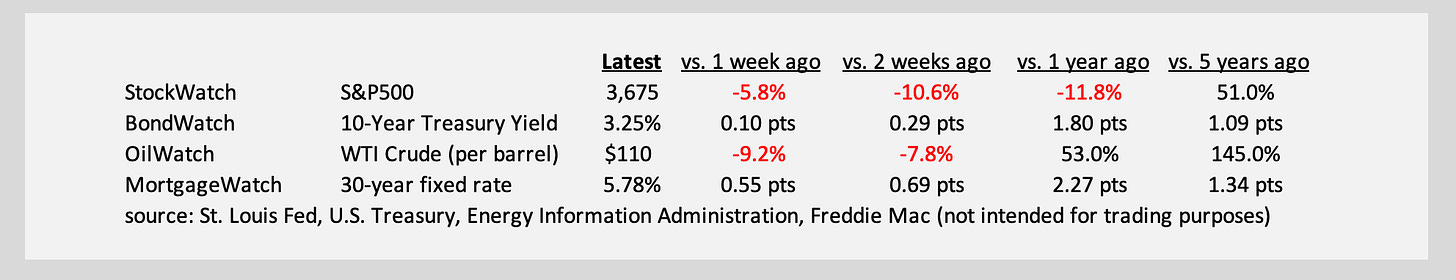

Market QuickLook

The Latest

“The Federal Open Market Committee decided today to lower its target for the federal funds rate 75 basis points.”

Wait a minute, the Fed lowered rates by 75 basis points? The statement is not from last week but from 14 years ago. It was the spring of 2008. Financial markets were increasingly stressed. The economy was clearly slowing. And “the inflation news,” as one committee member said, “has also been disturbing.” Another observed: “Household survey measures of expectations for year-ahead inflation jumped in March to their highest levels in about two years.” By August that year, oil prices had reached far above the $100 mark, lifting the consumer price index to a 5.6% annual increase. So much for the Fed’s 2% target. Alarm bells rang. But the Fed’s chairman at the time, Ben Bernanke, resisted calls to raise rates.

He made the right call. Five months later, annual CPI inflation was down to 0.1%. The economy had crashed, and oil prices along with it.

Fast forward to June 2022. Faced again with stressed financial markets, a weakening economy and discomforting levels of inflation, chairman Jay Powell and his FOMC colleagues voted to raise rates by 75 basis points. The economic backdrop, to be sure, is very different now. The economy is much healthier than it was in mid-2008, and inflation much worse. There is no housing bubble and no consumer credit crunch—just the opposite, in fact, with home equity at record highs and household balance sheets strong. Will Powell—like Bernanke 14 years earlier—be proved right?

Clearly, the Fed was spooked by the May CPI figures released a week earlier. It was hoping for signs that inflation was easing and got just the opposite. The latest read on inflation expectations, meanwhile, was similarly unsettling. And so, the Fed went with the three-quarter point hike, following a half-point hike at its previous meeting, and a quarter-point hike at the meeting before that. The FOMC will next meet again in late July, and Powell says another half- or three-quarter point hike is most likely. On the other hand, he said: “Clearly, today’s 75 basis point increase is an unusually large one, and I do not expect moves of this size to be common.”

Make no mistake, the Fed’s tighter monetary policy—the three successive hikes alongside balance sheet contraction—is working as intended. Perhaps most importantly, borrowing to buy a home has become significantly more expensive, with 30-year mortgage rates now approaching 6%—they were below 3% a year ago. Housing sales, if not prices, have thus plummeted. It’s become more expensive for the U.S. government to borrow as well—the 10-year Treasury note now offers lenders a 3.25% yield—that was 1.45% a year ago. The Fed’s moves, furthermore, have sent a chill through stock markets, sending the S&P 500 index down 12% from where it was this time last year. The crypto bubble popped. Labor markets are cooling. Corporate earnings are starting to show signs of strain. Ford, for one, says auto loan delinquencies are on the rise. And the latest retail sales report last week showed a 0.3% decline from April to May. Exclude spending at gas stations and the decline was 0.7%. Powell, by the way, said this was one of the most important reports he looks at.

There’s no ambiguity. The economy is slowing. But enough to cool inflation? Maybe, but not necessarily. The strong job market, healthy household balance sheets and still-solid corporate profits (including those from the booming commodity sector) might just be enough to sustain upward price momentum. In the meantime, the Fed’s aggressive tightening hasn’t been enough—at least not yet—to break the oil market. Prices did drop last week, to $110 per barrel from $121 the week before. But severe shortages of refinery capacity have gas prices still dangerously elevated. The Fed’s actions, furthermore, have done little to ease the semiconductor shortage (especially hurtful to the auto sector). They’ve done little to ease infrastructure bottlenecks (moving goods by rail, for example). They’ve done little to stem rising rents. If however, the Fed measures do continue to weaken demand throughout the economy, markets of all types could quickly reset.

In fact, this was a point Powell made. Supply didn’t or couldn’t react to last year’s sharply higher demand, causing the current price surge. But conversely, supply might not react to this year’s falling demand, which could make prices fall just as fast as they dropped. Oil prices, of course, have a habit of plummeting unexpectedly, as events from 2008 (not to mention 2014) made clear. Remember too that the last bout with inflation in the 1970s lasted so long because the Fed didn’t do anything about it until Paul Volcker came along a decade later. Mr. Powell might be a bit behind the curve, but not that far behind.

The point is, the Fed is determined to stop inflation with whatever it takes. That’s hopefully a soft landing, perhaps aided by declining oil prices but—if necessary—a recession. Its own forecasts, by the way, expect GDP growth of just 1.7% this year, down from the 2.8% growth it forecasted in March. It sees 1.7% growth next year too. Powell insists the economy remains healthy, with consumers in good shape and lowly consumer confidence mostly tied to rising gas prices.

Looking longer term, more economists are talking about the end of an era. For four decades, stock prices, bond prices and housing prices marched steadily upward, while goods prices steadily declined. Some ascribe the trend to easy money, loose Fed policy and macroeconomic forces like globalization, a positive Chinese labor supply shock, faster communications and cheaper container shipping. Now, it’s asset prices that are falling and goods prices that are rising, amid tighter Fed policy and a rash of negative supply-side shocks. The start of a new longterm trend?

As the answer to that question slowly unfolds, pay attention to a parade of Fed speeches this week. Chair Powell himself will testify before Congress, taking questions from legislators. This week also brings a few notable earnings calls, from FedEx, Accenture, Darden Restaurants, CarMax and the homebuilders Lennar and KB Home. Chrysler’s European parent company reports as well.

Companies

· Ford and General Motors: Detroit’s two largest automakers, both earning solid profits these days, each presented at the Deutsche Bank Global Auto Industry conference last week. Both companies said demand continues to be robust, though Ford did mention that payment delinquencies at its credit division are starting to increase, perhaps a leading indicator of some demand distress. But as Ford points out, if a recession were to come, it would enter from a position of strength, characterized by low inventories and minimal need for incentive pricing. Both manufacturers, meanwhile, continue to see cost pressures and production challenges, including higher commodity prices, disruptions at Chinese suppliers and a shortage of semiconductors. Interestingly, Ford said its new Mustang Mach-E electric car was profitable until commodity costs spiked. More importantly though, it expects a new generation of EVs to be solidly profitable once they start arriving in about four years. Not only will they be more cost-efficient, especially when produced at scale. But they’ll also generate more software and service revenues (subscriptions to in-car entertainment, for example, or upgrades to better driving features). GM said it’s taking lots of new orders for EVs but doesn’t want to lock in prices given the uncertainty of its future costs. It plans to produce 400,000 EVs in North America this year and next, and 1m by 2025. Ford insists it has all the supplies and materials it needs to build 600,000 EVs through the end of 2023 (for context, it delivered nearly 3m total vehicles in 2019). One big question is the future role of dealerships—Ford for its part sees them as an asset, providing important customer support that Tesla lacks (GM likely feels the same). Nevertheless, it’s being “very selective” in choosing which dealers can sell its Mach-E. Another question is EV advertising, where Ford is taking a more Tesla-like approach—Tesla basically doesn’t advertise at all, relying on its software to communicate and engage with customers. Unlike Ford, GM doesn’t have plans to split its company into two divisions, one for EVs and one for internal combustion vehicles (Ford will rely on profits from the latter to fund development of the former). In other matters of interest, Ford is considering equity stakes in even mining companies to secure its supply chain. Both firms are evaluating different battery chemistries. And both are developing EVs for the business market, as well as EVs with autonomous driving capability.

· Commercial Metals Company (CMC) is the largest North American manufacturer of steel reinforcing bar (“rebar”), a critical input for construction. Based in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, CMC sees no signs of a demand slowdown. On the contrary, it expects demand to remain strong and even grow in the years ahead, for three reasons. First is the new infrastructure bill. Second is the boom in Sun Belt single-family residential communities, which will boost the need for nearby roads, wastewater treatment, water supply, schools and shopping centers. The pace of single-family housing starts has slowed, it admits, but in the South, they’re still up more than 30% from 2019 and early 2020 levels. Finally, there’s the tailwind from industrial reshoring. CMC points to the “massive scale and pace of construction of new semiconductor facilities.” There are five such projects now underway in the U.S., including two each in Arizona and Texas. Management sees other industries growing domestic facilities as well in response to ongoing supply chain disruptions. “We have all learned over the last three years that global supply chains are more fragile than previously believed, and the loss of a few critical inputs can have a significant cascading effect throughout the economy.” CMC also mentioned that “offices and hotels are two market sectors that many had assumed would take years to recover if ever, but both are now making a comeback.”

· Kroger, the country’s largest supermarket (with 420,000 employees), said rising inflation has customers “rethinking their shopping and eating habits.” Americans, for one, are cooking more of their meals at home, after briefly returning to restaurants after the pandemic eased. More budget-conscious customers, Kroger said, “are actively looking for ways to save.” One random fact that came up in the company’s earnings call: Kroger is the nation’s largest florist. Remember that when Valentine’s Day comes around.

Tweet of the Week

Sectors

· Higher Education: It’s one of the notorious “Three H’s”—along with health care and housing—where market distortions and failures are rife. And it’s the topic of Charlie Eaton’s book: “Bankers in the Ivory Tower: The Troubling Rise of Financiers in U.S. Higher Education.” Appearing on the New Books Network podcast, Eaton explains how student loans were not always a significant factor in financing college. In the 1970s, he said, only one in eight graduates had any student debt. But things started to change after the harsh recession of the early 1980s. With jobs in short supply, college enrollment jumped, swelling federal expenditure on Pell grants. Congress subsequently slashed Pell grant spending, opening a door for bankers. By the early 1990s, banks were selling the idea of borrowing money to pay for school. And by 2010, student loan borrowing had quadrupled. Eaton separately spoke about the role of university endowments, which are pools of donated money, typically by alumni. For top schools these endowments have become enormously large thanks to successful investments and—according to an investigative report by The New York Times—controversial use of offshore tax havens. More specifically, the Times revealed that dozens of wealthy college endowments use Caribbean islands to cut their tax bills. Eaton explained that while college endowments are already tax exempt, they’ve increasingly worked with private equity and hedge funds, borrowing additional money to invest. And profits from these investments are in fact taxable because they’re not directly related to education. So there’s incentive to hide those profits in tax havens. Eaton says: “Private colleges and universities have increased their endowments spectacularly through aggressive fund-raising and these kinds of investment and tax-avoidance techniques.” He cites the example of California’s Stanford University, which used offshoring to help boost its endowment from $2b in 1977 to $18b in 2012. Over the same period, Harvard’s endowment grew from $6b to $32b. What’s the problem, besides depriving the public of tax dollars? Eaton says most of this endowment money benefits just a tiny elite. In Stanford’s case, it still only enrolls about 1,600 new freshmen every year, approximately the same number it enrolled annually in the 1970s. According to Stanford economist Raj Chetty, the top 38 private U.S. colleges today enroll more students from the top 1% of the nation’s income spectrum than from the bottom 60%. The point: That America’s best universities have become ultra-elite institutions, using their enormous wealth to educate just a tiny fraction of Americans. Here again is another manifestation of America’s shortage economy: too few workers, too few houses, too few port facilities, too few competitors in many industries, too few alternatives to fossil fuels … and yes, too few enrollments at top universities.

Markets

· Property Insurance: “Florida’s property insurance market is collapsing.” So says Mark Friedlander of the Insurance Information Institute, echoing many others as state residents see a surge in the cost of insuring their homes against damage. In the past three months, according to the “Sunshine Economy” podcast episode that aired in May, three Florida insurance companies have declared insolvency, another is canceling tens of thousands of policies and others are increasing monthly premiums by as much as 50%. Florida is by nature an expensive place to insure property because of its exposure to floods and hurricanes, risks that are escalating with climate change. The state even has its own taxpayer-backed insurer called Citizens to act as an insurer of last resort. Often, it’s the only insurer willing to take a risk on a property. Making matters worse recently is a surge in reinsurance rates—reinsurance is essentially insurance for the insurance companies; what they pay, in other words, to protect themselves against catastrophic losses. Another recent problem is inflation, driving up the cost of repairing a house when it’s damaged. Some blame excessive litigation—three quarters of all U.S. lawsuits involving home insurance claims are in Florida. One common practice is a contractor threatening to sue an insurance company unless it agrees to pay for a new roof after a storm—the insurance company often decides it’s better to just accept the claim than engage in a costly court battle. The state’s legislature recently passed some measures intended to address the situation, including more public money to help with reinsurance and new steps to curb frivolous lawsuits against insurers. But the problem could get worse, not better, as storms intensify. Miami, for one, is considered one of America’s most vulnerable cities to climate change.

Government

· Infrastructure: The U.S. government identifies 16 critical sectors “whose assets, systems, and networks, whether physical or virtual, are considered so vital to the United States that their incapacitation or destruction would have a debilitating effect on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination thereof.” What are these 16 sectors? Chemicals, commercial facilities (like shopping malls that draw large crowds), communications, critical manufacturing, dams, defense, emergency services, energy, financial services, food/agriculture, government facilities, health care, information technology, nuclear reactors, transportation systems and water systems. These are sectors that must continue to operate even during times of crisis, whether it be a pandemic or a war or a weather disaster.

Places:

· Detroit: He could have chosen 1913, when Detroit was fast becoming an economic superstar—thank the auto industry boom for that. He could have chosen 2013, when Detroit filed for bankruptcy—blame (in part) the auto industry gloom for that. Instead, journalist David Maraniss chose to write about Detroit at the midpoint of those two years: 1963. His book “Once in a Great City” depicts the Motor City at its pinnacle. GM, Ford and Chrysler were selling more cars than ever. Motown music was all the rage. The Civil Rights movement was advancing. The United Autoworkers union was gaining strength. And Detroit was America’s fifth-largest city, surpassed in population only by New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and Philadelphia. But even as its star shined brightest, the Motor City’s vulnerabilities began to show. Maraniss chronicles Detroit’s boiling racial tensions in the 1960s, culminating in severe riots during 1967. Wealthier white residents and manufacturing facilities began to flee for the suburbs. Inadequate housing was a major issue. Union battles with the automakers intensified (and grew costlier). Presaging the despair to come, Detroit narrowly lost its bid to host the 1968 summer Olympics, which instead went to Mexico City. The New Yorker magazine, reviewing the Maraniss book, likened Detroit in the early 1960s to “Humpty Dumpty’s most poignant moment being just before he toppled over.” As late as the final decade of the 1800s, nobody could have imagined the industrial colossus Detroit would become. It was always destined to have some commercial significance given its location along the Great Lakes, something its first settlers recognized in the 1700s. The Erie Canal boosted the town’s fortunes in the 1820s. Railroads turned it into a manufacturing center, large enough to become America’s 13th most populous city by 1900. Then along came Henry Ford, born on a farm in what’s today part of Detroit. In 1903, he incorporated the Ford Motor Company, selling a car he called the Model A. Five years later came the immensely successful Model T, produced in mass quantities at affordable prices thanks to Ford’s pioneering use of assembly lines. Though notorious for his bigotry, Henry Ford staffed his giant, vertically-integrated factories with European and Arab immigrants, farmers from Appalachia and—for the most menial jobs—African Americans escaping the Jim Crow South. In 1910, according to historian Ken Coleman speaking on NBC News, Detroit’s black population was less than 6,000 in 1910 but 120,000 by 1930, and 300,000 by 1950. Migration, indeed, both domestic and international, helped Detroit become the fourth largest city in America. The Great Depression, to be sure, was painful—GM cut half of its workers between 1929 and 1932, notes the Michigan League for Public Policy. But the 1930s gave way to a triumphant 1940s, when Detroit’s auto factories helped build the tanks, jeeps and planes America needed to win the second World War. The 1950s brought cheap gasoline, a big increase in female drivers, the construction of new highways, the onset of suburbanization and a golden era for the Big Three. In 1963, as Maraniss recounts in his book, Ford and its marketing chief Lee Iacocca was hard at work developing the Mustang, which would become one of the best-selling vehicles ever. During the 1970s, however, Detroit’s fortunes rapidly reversed. Oil was suddenly expensive. Japanese automakers enticed Americans with fuel-efficient cars. Suburban flight accelerated. More factories moved out of Detroit, if not to the suburbs, then to the South, or overseas. The Motor City was still the country’s fifth-largest city as late as 1980. By then, however, the U.S. economy was already reorienting away from manufacturing, in favor of service sectors like finance, health care, education, government and tourism. When the economy boomed in the 1990s, it was partly thanks to another era of ultra-cheap oil. Detroit’s carmakers responded with popular trucks and SUVs, boosting their financial standing. But the real action was in places like Silicon Valley with its information technology, New York City with its finance and tourism, and the Sun Belt with its housing boom and population growth. Chicago too, Detroit’s midwestern neighbor, would offset its manufacturing woes by becoming a hub for knowledge-intensive jobs and a magnet for tourists worldwide. By this time, it wasn’t just Detroit’s white population fleeing the city, but its middle-class black population as well, many even moving back to southern cities their parents and grandparents fled. They helped, for example, turn Atlanta into a quintessential 1990s boom city, on display during the 1996 Olympics. Whatever modest momentum Detroit did regain in the 1990s, it was anyhow lost in the dismal 2000s. High oil prices, ongoing competition from Japan and Germany, growing concerns about climate change, skyrocketing pension and health care obligations, a giant financial crisis in 2008… all conspired to drive GM and Chrysler into bankruptcy, kept alive only with a federal bailout. At its peak in 1950, 75% of people living in the Detroit metro area were living in the city itself. By 2010, one year after the GM and Chrysler bankruptcy filings, the percentage was just 39%. The nation’s fourth most populous city had become its twenty-fourth. Parts of its surrounding suburbs, to be clear, remained extremely affluent, growing with knowledge-intensive professional jobs—doctors, lawyers, auto executives, teachers, accountants, engineers, software developers, hospital administrators, etc. Today, health care and education employ more people in metro Detroit than auto manufacturing. That said, Ford, GM and Chrysler (known today as Stellantis) are still the area’s top three private employers, in that order. The city itself though, with fewer and fewer people, had little choice but to itself file for bankruptcy in 2013. A third of its residents (roughly three quarters of them African American) lived below the poverty line. The city’s debt was about $18b. Abandoned houses. Broken traffic lights. Rampant crime. Failing schools. You get the picture. Fortunately, the story starts to get better from here. The bankruptcy proceeding helped put the city of Detroit in a more fiscally sustainable position, to the point where it was even able to borrow in the bond market—without any state government guarantees—in 2018. For the first time in decades, a sizeable number of people began moving back to the city. Leading the charge was Dan Gilbert, arguably Detroit’s leading business figure today. He’s got nothing to do with the auto industry, but rather the housing industry—he’s the founder of Rocket, America’s largest mortgage lender. Gilbert’s companies currently employ about 20,000 people downtown. Other important employers include Wayne State University and the College for Creative Studies, a top design school. Detroit’s baseball, football, hockey and basketball teams all play downtown. Detroit will get a new bridge to neighboring Canada in 2024, to relieve traffic across the busy Ambassador bridge (which handled more than $300m worth of cross-border trade every day). The entire metro area, meanwhile, which lost 3% of its people in the 2000s, at least grew by 1% in the 2010s. The University of Michigan in nearby Ann Arbor is a critical economic institution. So is Detroit’s airport, a major Delta hub with nonstop flights to Europe and Asia. The federal government, including the Post Office, employs about 30,000 people in metro Detroit. And the automakers are reinvesting again, with GM for one refashioning its Detroit assembly plant as the launchpad for its electric vehicle strategy. Chrysler currently employs nearly 5,000 workers at its Detroit factory. In 2019, it announced a $1.6b investment in the facility, which is located within the city. Manufacturing still represents about 13% of all employment in the wider metro, down from 16% in 2000. The unemployment rate is down to 5.5%, and much lower in the suburbs—metro unemployment was 17% in 2009. The city itself remains troubled, with the lion’s share of new investment concentrated in relatively small areas of downtown, itself challenged by the work-from-home phenomenon. The pandemic of course didn’t make things any easier. The semicon shortage is making life tough for automakers. But the Big Three are nevertheless financially healthy and hiring, allocating at least some of their giant EV investment spending to their home city. It’s not 1963 anymore. But nor is it 2013. Perhaps in another 50 years, Detroit will again be an economic superstar. (Sources: Michigan League for Public Policy, NBC News, Census, Brookings Institution, Detroit Economic Growth Corporation, chart below sourced from the Dept. of Housing and Urban Development).

Looking Back

· Tesla: “Business Wars,” a podcast series, looked back at the rise of Tesla and its quest to upend the Detroit-centered auto industry. The narrative opens with Elon Musk on the verge of financial disaster at the time of the 2008 economic crisis. His companies Tesla, Solar City and SpaceX were all running out of money, kept alive only with Musk’s personal fortune earned from his PayPal days. At one point, Tesla had about three weeks left of cash. The company, to be clear, wasn’t Musk’s creation. It was founded in 2003 by entrepreneurs Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning. They convinced the temperamental Musk to invest and before long, Musk himself was running the show, forcing the founders out. Tesla in the meantime achieved important technological breakthroughs in its effort to address major challenges like how to prevent battery fires. Detroit, looking on with disdain, called Musk a “loud-mouth huckster,” to quote one GM executive. The Detroit Big Three weren’t exactly operating from a position of strength, however, losing billions and watching enviously as Toyota scored big with its hybrid Prius. Tesla was winning high-profile customers for its new Roadster, including California’s governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. But it was one-thing to build a $100,000-plus high-performance luxury sports car. Building an affordable EV luxury sedan, let alone a mass-produced mainstream vehicle, would be orders of magnitude tougher. Still, with the Roadster getting great reviews, Goldman Sachs agreed to provide funding. So did Germany’s Daimler. So did the U.S. government, hoping to spark investment in EVs. And so did Toyota, part of a deal to sell Tesla its idled $1b Fremont, California, factory for a bargain $42m—Toyota would get stock in Tesla upon the latter’s initial public share offering in 2010 (it sold the shares in 2017). Still Tesla faced many challenges, from navigating production complexities to dealing with battery fires to dealer resistance to its practice of selling cars directly to consumers. Cash would again dip to dangerously low levels in the early 2010s, as it tried to produce its Model S. But sales of the Model S were strong. Tesla would proceed to build its own giant battery “Giga-factory” in Nevada, in partnership with Japan’s Panasonic. The company expanded in China, today the world’s largest market for autos. It led the way on advancements in autonomous driving, pledging to populate the world’s streets with a fleet of Tesla robo-taxis. In 2017, Tesla debuted the Model 3, priced for the mass market. It too proved extremely popular, so much so that Tesla became the world’s most valuable car company, making Elon Musk the richest person in the world. But not without controversy. Impulsive Tweeting, legal troubles, smoking weed on the Joe Rogan podcast, expressing political opinions… all have made Elon Musk a love-him or hate-him figure. Detroit, meanwhile, has followed in Elon’s footsteps, investing billions in phasing out gas-powered vehicles in favor of EVs. One person, discussing lengthy waits to get his Tesla repaired, said he felt like a Cubs fan: extremely loyal but extremely frustrated.

· Regarding Tesla, the latest edition of The Economist features an article entitled “The great Teslafication: How supply-chain turmoil is remaking the car industry.” It describes how even Detroit’s Big Three are now emulating much of Tesla’s strategies, including more vertical integration (doing everything under one roof) and turning cars into computers on wheels (relying as much on processing power as horsepower). Tesla has in fact suffered less from the semiconductor shortage because it designs its own chips and works closely with the firms that manufacturer them.

Looking Ahead

· The Future of Social Security: C-Span’s Washington Journal aired a talk on the future of Social Security, featuring Max Richtman of the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare (he’s a big defender of the programs), and Joseph Antos of the American Enterprise Institute (he’s warning about their fiscal sustainability). The discussion centered on a recent report concluding that by around 2035, the program will only have funds to pay about 75% of promised benefits. But the dates could change based on payroll tax collection, inflation, GDP growth and other factors. The Social Security Administration, by the way, estimates that Social Security benefits will provide on average about 40% of what a person earned on average through their career. That’s clearly not enough to maintain one’s standard of living in retirement, meaning personal savings and private pension investments are also important. So how to fix the future funding problem? How, in other words, to ensure that the Social Security trust fund can continue to pay full benefits? One option is to reduce some benefits—raising the retirement age or lowering annual cost of living adjustments, for example, or reducing payouts to high-income earners. An alternative is to boost the fund’s revenues through Congressional appropriation, something Richtman advocates. Raising the payroll tax from the current 12.4% to 15.6%, meanwhile, would eliminate any longterm funding shortfalls, according to official estimates. Applying the tax to income over $147,000 per year (the current cap) would help too. Some prefer a wealth tax, or a tax on health insurance plans offered by companies. Some would rather raise revenues (or at least attempt to do so) by investing funds in assets riskier than Treasury debt, like stocks or corporate bonds. A final note: The Social Security trust fund gets about 93% of its revenue from taxes (mostly payroll taxes paid by covered workers and their employers). The other 7% is mostly from interest earned on investing funds in U.S. Treasury bonds.