The Durable Dollar

Plus: This Week's Featured Place: Kansas City, Missouri, Yesteryear’s Vegas of the Plains

Issue 65: April 25, 2022

Inside this Issue:

Top Dollar: U.S. Currency Showing its Appreciation

Nuclear Bonds: A Bloody Outcome for Fixed Income

For Doves, Powell Disappoints: Says Fed Might Hike by 50 Points

Streaming of Better Days: Netflix Bears Tank its Shares

Uncommon Comment: Health Insurer Anthem Downplays Inflation

Bubble Trouble? Four Reasons Why for Housing, it’s Not 2008

Gas Extinction: America’s Gas Stations Face Existential Threat

The Re-Shoring Conundrum: Firms Bring Jobs Back but Labor They Lack

And This Week’s Featured Place: Kansas City, Missouri, Yesteryear’s Vegas of the Plains

Reminder: The Econ Weekly podcast is now available on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Podcasts and Spotify. Just search for Econ Weekly and please leave a review to help spread the word.

Quote of the Week

“The bond market, the banking system, the financial system is not really designed to have the entire bond market lose 10% of its value in four months. Every other time we’ve seen this we’ve always run into problems.”

- Jim Bianco of Bianco Research, speaking on Bloomberg Surveillance

Market QuickLook

The Latest

Inflation running wild. An $860b trade deficit. More than $28 trillion in federal debt. An uncertain U.S. growth outlook. Heightened interest among governments to transact in other currencies. Doesn’t sound like the backdrop for a strong U.S. dollar. Yet the dollar has indeed been super-strong lately, lifted by the Fed’s increasingly forceful pledge to gun down rising prices with rising interest rates.

Rising U.S. interest rates, to be sure, make U.S. dollars more valuable—you can earn more by lending them out, even if just to Uncle Sam in exchange for a Treasury bond. As the Wall Street Journal’s Joseph C. Sternberg wrote last week: “Investors are flooding into the greenback because the Federal Reserve seems to be tightening more aggressively than any of its major peers.”

So, is this a good thing or a bad thing? Bad, if you’re an American selling stuff to foreigners. But good if you’re an American buying stuff from foreigners, meaning the strong dollar should help a bit with inflation. In February alone, Americans bought $318b worth of goods and services from foreigners, including $73b of consumer goods, $29b of automobiles (including parts), $16b of crude oil and $6b of semiconductors. Again, that’s just during the month of February.

Unfortunately, the dollar’s helpful impact on inflation is more than offset by countervailing forces, most importantly supply-side disruptions that just won’t go away. In fact, they could get worse with Covid lockdowns affecting Chinese ports and factories—and with commodity markets upended by the war in Ukraine. Demand, meanwhile, continues to hold more or less firm, as the latest corporate earnings reports seem to indicate. A newly-published S&P Global survey of purchase managers likewise suggests ongoing economic strength, albeit with some hints of pessimism—there’s understandably some concern among companies that repeated price hikes (to offset rising costs for labor and materials) will eventually dent consumer spending.

That’s the situation as the Fed inches closer to its greatly anticipated meeting next week (May 3-4). At an IMF event last week, Fed chief Jay Powell affirmed that a half-point rate hike was “on the table,” and that policymakers will no longer stand by and wait for supply chain relief for inflation relief—that’s out of the Fed’s control. Powell made clear it’s “appropriate in my view to be moving a little more quickly,” sending yet another signal of the Fed’s hawkish intent. Treasury yields rose again in response, further battering the values of existing Treasuries issued with lower rates. Corporate bond values were naturally affected as well. An important point about the Treasury market though: Their declines last week were again more pronounced at the midpoint of the time curve (the two-year rose the most). The gains were more muted for longer duration borrowing like the 10-year and 20-year. That’s a likely sign of investor bearishness about longer-term GDP trends. An anticipation, perhaps, that the Fed will at some point have to reverse course and start lowering rates again, maybe in response to another demand shock. Others see longer-term rates depressed due to simple demographics, with America’s shrinking labor force destined to constrain future GDP growth (as it’s arguably doing already).

Powell, at the IMF event, did make sure to say that the U.S. economy looked strong, with “a lot to like” about the labor market. He also suggested though, that the world economy could be entering a more fragmented state, threatening the efficiency—though also avoiding the risks—of hyper-efficient global supply chains. The IMF incidentally lowered its forecast for global GDP growth this year, to 3.6%. Russia’s sanction-battered economy is one reason. The worsening food and energy crisis affecting developing nations is another. Still another is the pressure exerted by the strong dollar. Consider Japan, which usually likes a strong dollar because it sells so many cars and whatnot to Americans. But it also needs to pay for its imported oil and other commodities in dollars, one of which now exchanges for about 128 yen. At the start of 2021, it only took 104 yen to buy a dollar.

Back and home, there’s no longer any doubt that the housing market is slowing, cooled by sharply rising mortgage rates—the U.S. Treasury might not be seeing a sharp rise in 30-year borrowing costs, but homebuyers sure are (their average rate’s now 5.11%, according to Freddie Mac). From February to March, home sales under contract fell 4%, said the National Association of Realtors. Existing home sales fell 3%.

The Fed’s latest Beige Book came out last week, as always providing insightful anecdotes about economic conditions across the country. All throughout are tales of frustration about supply chains and labor shortages but also encouraging descriptions of demand. The New York Fed, for one, described businesses with “severe shortages of truck drivers, construction workers, IT staff and human resource professionals.” Some, it added, “have grown less picky about required qualifications for open jobs and have become more flexible about remote work arrangements.” On a brighter note, New York City is seeing a rebound in its critical tourism sector, with domestic visits now back to within about 90% of normal levels, and visits from abroad about 65% back to normal. The New York Fed, incidentally, also said “residential rents across the district have trended up briskly.”

Also in the Beige Book, The St. Louis Fed said one of its contacts in trailer manufacturing believed they “could double their sales if they had the workers.” Hospitals, meanwhile, “continue to face shortages of nurses and lab supplies.” Makes you wonder if it’s time to reverse recent moves to decrease immigration and increase tariffs.

Everyone’s still wondering if Elon Musk will wind up controlling Twitter. Blackstone, the asset manager specializing in private equity, took a bet on student housing. Student loans, meanwhile, remain a topic of debate in Washington—should the government cancel the debt? According to the Education Data Initiative, 43m Americans owe $1.6 trillion to the Department of Education. The issue is further complicated by concerns about racial equality, with Black students most likely to finance their college studies with federal loans.

It's now the thick of Q1 earnings season, with last week featuring its share of good performances and bad. Mr. Musk dazzled investors with excellent results for Tesla. Bank of America sounded bullish on the U.S. economy and the U.S. consumer, pointing to household deposits and cash levels that remain $3 trillion higher than they were before Covid. CEO Brian Moynihan asked: “Could a slowdown in the economy happen? Perhaps. But… consumer spending remains strong, unemployment is low and wages are rising. Company earnings are also generally strong. Credit is widely available. And our customers’ usage of their lines of credit is still low, i.e., they have capacity to borrow more.” Sounds bullish, no?

More bearishly, Netflix saw its stock price take an epic tumble, unnerving investors with post-pandemic subscription declines. CNN’s new subscription offering, meanwhile, lasted less time than it takes Anderson Cooper to utter the words “BREAKING NEWS!” (i.e., a celebrity’s cat got caught in a tree). Signs of a popping bubble in streaming media? In the transportation world, airlines are flying high thanks to insatiable leisure demand, but freight railroads—though extraordinarily profitable—have shippers up in arms over unreliable service. Truckers, for their part, downplayed talk of a looming freight recession. As the trucking firm Knight-Swift told investors: “Reports of the death of the freight market… have been greatly exaggerated.”

This week, the earnings spotlight turns to Silicon Valley and Silicon Seattle, with Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Meta and Alphabet all reporting. ExxonMobil and Chevron go as well, offering new insights on the turbulent oil market. Oil prices, by the way, dropped a bit last week, but not enough to save the stock market from another decline. With the bond market in meltdown as well, investors have their hands full.

Companies

Netflix was a poster child for pandemic-era prosperity. People confined to their homes were subscribing to its streaming video service in droves. The company’s stock price went higher and higher, at one point topping $700 a share (it was $329 at the start of 2020). Then came last autumn, when investors began losing their appetite. It was partly a lost appetite for all high-flying IT growth stocks, which looked less appealing in the face of rising interest rates (see item below). It was more than just getting caught up in the moment, however. Netflix roused specific concerns, one being the surge in competition—Disney, AT&T, Paramount, Apple, Amazon, Comcast, Hulu, Discovery, YouTube… the better question might be who isn’t offering a streaming video service these days? Amid this worry came last week’s Q1 earnings report, which downright alarmed Netflix investors. Shares plummeted 35%, ending the week at $ To be clear, the company reported solid profits. And it’s still the leader by far in number of paid subscribers—220m at the end of Q1. But for the first time in a decade, the company is losing subscribers, including a sizeable number in Russia. People around the world, it seems, are predictably spending less time watching television now that Covid fears have eased in most places. Inflation doesn’t help, with Americans pressed by higher gas prices, for example, perhaps less willing to subscribe (Netflix itself raised prices earlier this year). To help win back investor good graces, management is tackling a long-vexing problem, namely the huge number of customers that share their passwords with friends and family. It estimates that 100m households watch Netflix using another household’s account. The company is also considering a cheaper service that includes advertising, something co-founder and CEO Reed Hastings has long resisted. Streaming video games are another area of potential revenue growth—it’s a huge market but likewise highly competitive. It’s now been nearly 20 years since Netflix, born in Silicon Valley, burst on the scene and drove video rental stores like Blockbuster to the dustbin of history. In the early days, it was DVDs with licensed shows and movies, sent to people’s homes via the mail. Now it’s internet-delivered, on-demand television, filled with original programming produced (at heavy cost) in-house. From House of Cards to Squid Games, Netflix has become a global cultural phenomenon. But has its business model reached a peak?

A quick word on why investors lose their appetite for growth stocks when interest rates rise. It’s because of the financial world’s most important concept: The time value of money. Growth implies dollars earned in the future. But the higher interest rates go, the more valuable it is to hold dollars in the present. It’s less appealing, in other words, to wait for your money, i.e., to buy growth stocks. Inflation, of course, also erodes the value of future money. Consider someone who manages a retirement fund. The goal is to grow a pool of money over a long period. If interest rates are low, it’s harder to grow that pool, so you might be inclined to buy riskier assets like tech stocks. As interest rates move higher, safer bonds tend to look more attractive, especially if held to maturity. O.K. wait a minute, then why are bond prices tanking? Because for those who trade bonds before they mature, rising rates are a curse (remember, there’s a “primary” or new bond market and a “secondary” or pre-owned bond market, to use a car analogy). That bond you bought yesterday at 2%? It’s now worth much less in the secondary market with rates having moved to 3%. And so another cardinal rule from the world of finance: When rates rise, bond prices in the secondary market drop (and vice versa).

Omnicom is a global marketing agency based in New York City, not to be confused with the Covid variant Omicron. The company, reporting earnings last week, naturally welcomed the possibility that Netflix might start running ads. Said CEO John Wren: “In the environment where the consumer has to be a little bit more cautious of the amount of money they spend to get what they want, I think you’re going to see more and more advertising in some of these services.”

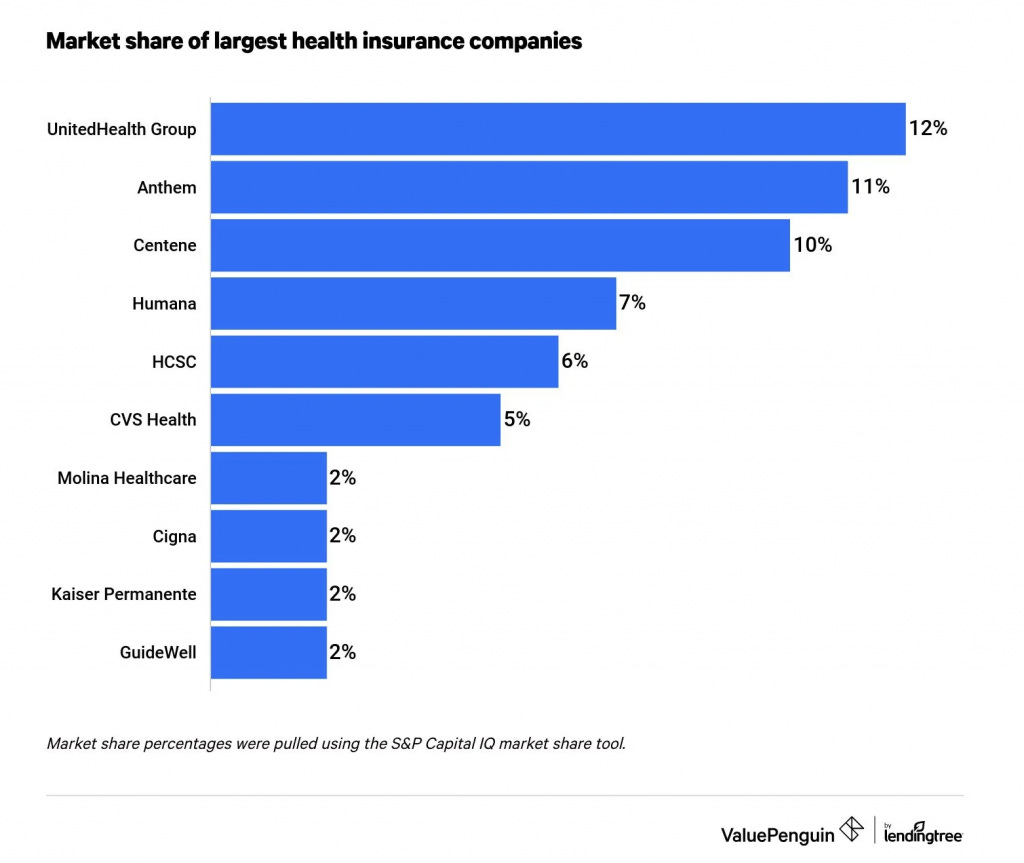

Anthem: During the decades-long stretch of low inflation in the U.S. economy, the one major exception was health care. Now that inflation is raging, ironically, health care is the one area where costs have remained relatively restrained. In the March consumer price index, medical care showed just a 2.9% y/y increase. Anthem, the country’s second largest health insurer after UnitedHealth, said in its Q1 earnings call that it’s no doubt seeing cost pressure from a tight labor market. Many of the care providers it works with (i.e., doctors and nurses) face higher costs of supplies and other essentials. But for insurers, the number one cost item is what hospitals are charging for services. Anthem typically negotiates contracts with hospitals that last for three years, so prices don’t move around all that much. There has been some upward movement, it said, “but at this point, we’re not seeing incremental rate pressure.” Like other insurers, Anthem is trying to move to a system where it pays hospitals and doctors based on health outcomes (“value-based care”) rather than just the quantity of tests and services they do (the “fee-for-service model”). How its efforts unfold are of great significance to the entire U.S. economy, a fifth of which involves health care.

Tweet of the Week

Sectors

Gas Stations: Recode’s Rebecca Heilweil writes about the likely demise of gas stations as electric cars and trucks proliferate. Some stations are installing chargers themselves to serve this new market, but many electric vehicle drivers do their charging at home or at charging stations in shopping center parking lots. In California, Tesla opened a charging hub for its vehicles that incorporates a lounge, an espresso bar and free Wi-Fi. In Norway, where 90% of new cars sold are EVs, gas station visits are way down. Back in the U.S., a big push is underway, backed by federal money, to install charging stations across the nation’s road network. Heilweil describes gas stations as the “middlemen between the fossil fuel industry and drivers.” She writes: “Oil companies need a place where they can easily distribute their product to customers, and drivers need a convenient, reliable spot to fill their gas tanks.” Gas stations, of course, don’t just sell gas. Econ Weekly’s issue from Oct. 11, 2021, looked at their underlying business model, referencing a profile by journalist Zachary Crockett. Most stations don’t earn much profit (if any) selling gas itself. Instead, they earn generally high profit margins from the convenience stores they operate, selling everything from snacks to energy drinks to alcohol to cigarettes to lottery tickets. To lure customers in, offering restrooms is key. And perhaps gas stations will remain the most convenient place to stop for a restroom break. Or maybe not. In Heilweil’s words, “the phasing out of travel by horse also meant the demise of the horse-drawn carriage industry and the repurposing of stables. Now, after a century spent building complex infrastructure around gas-powered vehicles, another transition seems inevitable.”

Markets

Housing: Ben Carlson, co-host of the “Animal Spirits” podcast and author of a blog called “A Wealth of Common Sense”, gave four reasons why a slowing housing market doesn’t mean a repeat of the 2008 housing collapse. 1) The large millennial demographic is now reaching prime home buying age, which supports demand. 2) Housing supply nationwide is extremely tight after years of underbuilding. 3) There’s hardly any rush for existing homeowners to sell because many are luckily locked into low mortgage rates. And 4) Household balance sheets are strong, meaning there’s still plenty of spending power to buy new homes even if mortgage rates have moved higher. On the other hand, it’s a terrible time to be a first-time homebuyer.

Gas: Bank of America said that while fuel costs are up 40%-plus from last year, fuel today represents only about 6% of overall debit and credit card spending among U.S. households. It probably helps that more people are working from home rather than driving to an office.

Labor

The U.S. lost a lot of manufacturing jobs in the past half-century-plus. Can it win some back? Yes, it seems, as companies reorder their priorities in the wake of the supply chain crisis. Build more at home, the theory goes, because it’s less risky even if more expensive. Chris Kuehl of Armada Corporate Intelligence, however, raises an important point. Speaking at a Kansas City Chamber event in December, he highlights the extremely tight U.S. labor market as an impediment to reshoring. The simple demographic reality is that every month, 10,000 Baby Boomers are reaching retirement age, he said. And after years of low birth rates and the recent decline in immigration, staffing existing manufacturing jobs is difficult, let alone new ones. He separately mentioned another overlooked challenge: That many communities don’t want manufacturing jobs, fearing more traffic, noise, pollution, loss of open land, unsightly buildings, etc. Which U.S. states, by the way, are leading the nation in manufacturing job growth? Kuehl names Texas, Oklahoma and Arizona.

The Economist ran a piece about India’s leading IT services firms, namely Tata Consulting (TCS), Infosys and Wipro. Their armies of low-cost coders first assumed a meaningful role in the U.S. economy during the Y2K scare leading up to 2000, helping U.S. companies ensure their software wouldn’t crash at the turn of the millennium. More recently, they proved useful in helping companies transition to remote working during the pandemic. They’re now involved with important transitions like the shift to electric vehicles and the transfer of data and computing to the cloud. The Indian firms are busy writing code for cybersecurity software as well. U.S. firms themselves are hiring people in India. IBM for one has opened a cybersecurity office there, catering to its Asian clients. JPMorgan Chase, The Economist adds, plans to add 6,000 people to its Indian workforce, developing artificial intelligence software among other things. The article notes: “Wages for new hires in India can be as little as $5,000 annually, less than a tenth of the going rate in rich countries. Even factoring in other costs, Indian projects are at least 20% cheaper than the same endeavors in the West, estimates Peter Bendor-Samuel, boss of the Everest Group, a consultancy.” Indian wages are rising, however—McKinsey estimates that compensation costs have risen by 20%-to-30% over the past year. To be clear, India’s big IT firms don’t just do work in India. Infosys alone has more than 30 outposts across the U.S. and is building a new $245m campus in Indianapolis. It plans to add 10,000 American workers in the next few years, bringing the total to 35,000. That said, most of the value U.S. companies derive is from offshore outsourcing the IT work, which is politically controversial—the U.S. doesn’t want to lose white-collar jobs to offshoring like it lost so many blue-collar jobs. It’s also becoming harder to secure visas for Indian software engineers to work in the U.S., another common practice. Take a PATH train from New Jersey to Wall Street on any given weekday, and you’ll see it filled with Indian software engineers employed on temporary visas.

Government

North Carolina State Treasurer Dale Folwell, speaking several weeks ago on the Bond Buyer podcast, had not-so-nice things to say about the health care industry. He called it a cartel, controlled in large part by Wall Street, alongside “multibillion dollar corporations that disguise themselves as non-profits to avoid taxation. North Carolina’s government has nearly 750,000 employees on the state’s health insurance plan, which of course gets more costly as health care costs rise. Folwell, by the way, also chairs North Carolina’s Local Government Commission, or LGC, which decides which entities can borrow money using tax-free bonds. Typical candidates include water and sewer districts, along with universities and hospitals.

Places

Kansas City, Missouri: A sleepy midwestern town? That might be its reputation today, fairly or unfairly. But that was certainly not the case a century ago. During the prohibition-era of the 1920s, and even into the Depression years of the 1930s, Kansas City was more associated with adjectives like sinful, sketchy, edgy and perhaps what we’d today call Las Vegas-like. There’s a reason why Wilbert Harrison went there to chase women and wine, as “Kanas City,” his number one hit song from 1959 recounts. America’s most geographically central metro started out like many cities on the western lands once owned by France—as a place to trade furs. It is, after all, located where the Missouri and Kansas Rivers meet, quite conveniently for river commerce. When the railroads came and expanded after the Civil War, Kansas City boomed, becoming a mini-Chicago of sorts. It was number two behind Chicago in meatpacking, for example, and likewise served as a commercial hub for surrounding farm products—a place to buy and sell grains and seeds and animals, etc. It also, less welcomingly, mimicked some of Chicago less-flattering characteristics, including government corruption and organized crime. Amid a wave of impoverished European immigrants, one family’s arrival from Ireland would shape the city for decades. The Pendergasts, led by brothers Jim and later Tom, built one of America’s most powerful urban political machines, on par with the Dailey machine in Chicago or Tammany Hall in New York City. In the meantime, by the early 1900s, Black Americans eager to escape the South rode the rails and busses northward in search of better lives. Amid these migrants were many musicians from New Orleans, destined to turn Kansas City into one of the great Jazz capitals of America. The Pendergast machine, working closely with organized criminal syndicates, made sure the nightclubs and gambling dens were open, and that the alcohol freely flowed, even during the Prohibition years. Gambling. Seedy nightclubs. You get the picture. It’s much different to be sure, than today’s image of Kansas City. Post-World War II suburbanization changed the city’s downtown character, robbing it of its vibrancy until some measures of revival more recently. It’s never experienced an urban renaissance like Chicago though, in part because it simply doesn’t have the scale to be a global commercial and tourist hub. What it does have is a fairly diverse economy with an above-average workforce of professionals. It’s still a leading transportation hub, with more rail traffic than anywhere but Chicago. That’s unsurprising given its geographic centrality, which makes it a major trucking hub as well. It punches below its weight in air traffic, however, owing to its limited tourism and modest size (it’s the country’s 35th largest metro by population). But its aviation heft should improve with the modernization of its airport now underway. That alone is a project providing lots of construction jobs. Kansas City is attracting more than its fair share of new facilities characteristic of the 21st century economy, including call centers, health facilities and especially warehouses. Meta, owner of Facebook, is building an $800m data center. Kansas City, which straddles the states of Missouri and Kansas, has plenty of prosperous suburbs, major league baseball and football franchises and decent population growth (7% during the 2010s). Though neither state capital nor home to a large university, the area has one of the largest federal government workforces (non-military) outside of Washington. The IRS alone has nearly 5,000 workers in Kansas City. After Uncle Sam, the largest metro area employer is a hospital, followed by Cerner, a health care technology firm with nearly $6b in revenue last year. Hallmark, H&R Block and the investment firm American Century are other familiar corporate names with Kansas City headquarters. Thanks in part to its distributional and logistic advantages, the area is home to major GM and Ford auto plants. The Ford plant is in fact one of the country’s largest, building the company’s most popular product, the F-150 pickup. Honeywell, an aerospace giant, is helping to modernize the country’s nuclear weapons at its Kansas City facilities. Grain and livestock processing, an old staple from the city’s past, remains important today (the local baseball team got its name from an annual livestock show called the American Royal). The city likewise remains home to one of 12 Federal Reserve banks across the country (oddly enough, St. Louis, Missouri, has one too). Kansas City officials do express some concern about mergers that have swallowed some prominent corporate citizens, including Sprint (purchased by T-Mobile) and DST Systems (purchased by SS&C). A Canadian railroad is now buying Kanas City Southern, though their combined network (assuming the merger is approved) could boost the city’s stature as a gateway for traffic moving between Mexico and Canada. There have been some high-profile factory closures in recent years, including those by Harley Davidson and Procter and Gamble. In sum, Kansas City has a solid economy with solid population growth, outperforming other midwestern cities that peaked in national prominence during the first half of the 20th But nor is it a growth superstar in the vein of say, Austin, Nashville, Charlotte or Denver. The nickname “Paris of the Plains” sounds a bit hyperbolic. But better that, surely, than being the subject of songs about sin. (Sources: HUD, Census, Mid-America Regional Council, Economic Development Corporation of Kansas City, KC Chamber).

Kansas City: If you’ve ever read David McCullough’s classic biography about Harry Truman, you might recall a chapter about the President’s experience as a men’s clothing store owner, and later a civil servant, in Kansas City during the 1920s. It portrays the city under the control of the exceedingly corrupt Pendergast political machine, which doled out everything from construction contracts to liquor licenses—to supporters, of course. It’s a good look at how political machines develop and operate, in this case with the elder Pendergast arriving from Ireland in the 1870s, at first working in a slaughterhouse and later an iron foundry. After winning money by gambling, he purchased a hotel and saloon where other people could come to gamble. Later came wholesale liquor distribution. Then election to local office. Then using public money to build loyalty among Irish immigrants and other poor and needy citizens of Kansas City. McCullough writes that he reached out to the city’s Polish, Slavic and Italian communities, and even its African Americans. Kansas City, by the way, continued to experience a construction boom beyond the roaring 1920s and well into the Great Depression. You might even call it the Austin of that era.

Wichita, Kansas, is a major hub for aircraft manufacturing, thanks to companies like Boeing supplier Spirit AeroSystems. No surprise then, that the Canadian planemaker Bombardier just announced Wichita as its new U.S. headquarters. (See Econ Weekly’s issue from May 24th, 2021).

Looking Back

General Motors: Alfred P. Sloan, Jr., the greatest business leader in American history? The American Business History Center makes the case as it profiles his career. Sloan ran General Motors from 1923 to 1956, quite a feat of managerial longevity. Before his arrival, GM was earning much lower profits than its rival Ford, whose founder Henry Ford pioneered the use of assembly lines and other revolutionary production methods. By the time Sloan retired, GM had become America’s largest company, with profits significantly higher than those of not just Ford but also the next two largest U.S. companies: Standard Oil of New Jersey (now ExxonMobil) and AT&T. Along the way, Sloan introduced management practices that were arguably as groundbreaking as the assembly line. He centralized and modernized many core functions, including financial controls, product design, research and development, marketing, legal matters, purchasing, real estate and factory design. Yet GM also stressed decentralization, with operating division managers given full autonomy over their “profit center.” Earlier, under former CEO Billy Durant, headquarters had little idea of how each division operated and whether it was truly profitable or not, often leading to costly overproduction. Sloan’s system also separated corporate strategic decisions (i.e., where to invest) from operating decisions (executing and implementing). The former were largely made by committees rather than individuals. This produced the multi-brand portfolio that GM still sports today, marketing different products to people with different income levels—“Chevrolet making starter cars, Pontiac offering a step up, Oldsmobile and Buick even higher, and Cadillac at the top, with slightly overlapping pricing.” Remarkably, GM under Sloan didn’t even lose money during the Great Depression of the 1930s. During World War II, it was the single largest supplier to the U.S. military. By mid-century, GM was at the center of the U.S. economy, employing some 600,000 American workers. The American Business History Center’s Gary Hoover, who authored the profile, further details Sloan’s legacy, including his relationship with dealers and unions. Today, thanks to philanthropy, his name graces MIT’s Sloan management school, as well as the Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

Looking Ahead

Climate Change: To understand how the economy reacts to a warming planet, watch the insurance industry. That’s one takeaway from Eugene Linden, author of the new book “Fire and Flood: A People’s History of Climate Change, from 1979 to the Present.” Appearing on the Bloomberg BusinessWeek podcast Linden says insurance firms are often underpricing climate risk, partly because they can offload some of that risk to reinsurers (not unlike mortgage underwriters offloaded risk during the ill-fated 2000s housing boom). On the other hand, property insurance companies have been leaving the Florida market for years, forcing the state government (in 2002) to form its own non-profit insurer. The state is experiencing somewhat of an insurance crisis in 2022, with more firms pulling out. The insurer AIG, Linden notes, left the California market where wildfires are costly to cover. Unhelpfully, many of the country’s hottest housing markets during the pandemic were in the most climate-vulnerable places—think coastal cities like Miami. At some point, Linden thinks, it will become simply too expensive to insure property in such places. Without insurance, banks won’t provide mortgage loans. And that, Linden says, could trigger a 2008-like mortgage crisis.

Climate Change: Along those same lines regarding risks to property, Jenny Schuetz fears the current U.S. housing stock simply isn’t adequate to meet the challenge. Speaking on the New Bazaar podcast, she gives the example of basement apartments in New York that flooded during a recent hurricane, and homes in the Pacific Northwest that weren’t built with air conditioners to handle the coming extreme heat. Schuetz is the author of the new book: “Fixer-Upper: How to Repair America's Broken Housing System.”