Retail Sales Strong... But Money and Oil Getting Costlier

PLUS: This Week's Featured Place: Bentonville, Arkansas

Issue 56: February 21, 2022

photo courtesy of Visit Bentonville

Issue 56: February 21, 2022

Inside this Issue:

Americans Still Shopping: Retail Sales Growing Not Dropping

Rate-ist Hits: Will More Expensive Borrowing Derail Consumers?

Oiler Spoiler: Will More Expensive Fuel Derail Consumers?

Another Brick in the Wal: Once Again, Walmart Shines Bright

Four-Wheel Fortune: It’s the Worst Time Ever to Buy a Car

Who’s Gonna Watch Little Emma? America’s Childcare Dilemma

Sheets Hard to Value: How Venture Cap Filled a Financing Gap

A Post-Crisis World: A How Global Finance has Changed Since 2008

And This Week’s Featured Place: Bentonville, Arkansas, Land of Sam

To hear an audio discussion of this week’s issue, follow Econ Weekly on LinkedIn or Twitter

Quote of the Week

“The world of yesterday was insufficient demand. The world of today is insufficient supply.”

-Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic adviser at Allianz

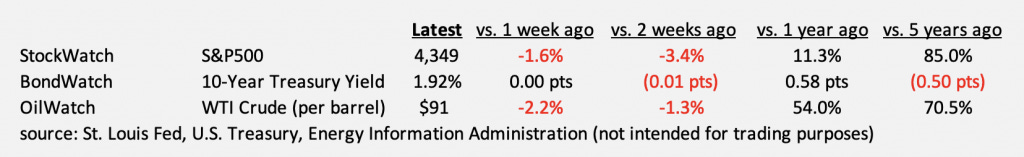

Market QuickLook

The Latest

As consumer spending goes, so goes the U.S. economy. Well then, are Americans still spending?

Yes, they are. Retail sales, the Census Bureau showed, rose nearly 4% from December to January, despite the omicron wave (that hurt December sales) and despite surveys showing high levels of consumer pessimism. Of course, shoppers are getting less for their money with inflation running high. But don’t let that disguise the fact that overall spending from November through January was up a scorching 16% y/y.

As you can see from this chart, online sales jumped in January (that’s probably an omicron thing) while spending at gas stations receded a bit. Importantly, vehicle sales increased solidly, perhaps a sign of improving availability. Just five categories of businesses—auto dealers, online merchants, supermarkets, general merchandise stores and restaurants—account for roughly 70% of all U.S. retail spending. To be clear, the retail sales report doesn’t capture consumer spending on services like health care, education, financial products, transportation and leisure. That’s an even bigger number.

Nevertheless, it’s an unmistakably bullish sign when Walmart, America’s largest retailer, says it still sees consumer strength. AutoNation, America’s top seller of vehicles, sees the same. So does Bank of America as it monitors trends in credit card usage.

It’s not a consumer good, but people are still buying houses too. Sales of existing homes rose 7% in January (from December), according to the National Association of Realtors. (Punta Gorda, on Florida’s Gulf Coast, is the nation’s hottest housing market with prices up nearly 30% y/y). January’s jump in homebuying, however, was likely influenced by shoppers eager to buy before mortgage rates move any higher. They’re starting to rise, of course, in anticipation of March 16th. That’s the day Fed chief Jay Powell announces his next move on interest rates. He and his FOMC colleagues are all but certain to lift the Fed’s overnight rate target by at least a quarter point.

Will that slow consumer spending? The Fed sort of hopes it will, if doing so defeats the inflation demon. It might get some unwanted help in rising oil prices, probably an even bigger threat to consumer spending. Though prices fell last week, they remain exceedingly high and poised for further gains amid Russia’s maneuvers around Ukraine. The U.S. economy isn’t as vulnerable to expensive oil as it once was, in part because its own energy sector has grown in economic significance—parts of the U.S. like West Texas do well when oil prices rise (just as parts of the economy like banking do well when interest rates rise). Still, the net impact is negative, fueling much of the current inflation and straining household finances as they fill their cars with gas. Pricey oil likewise drives higher costs for businesses, some of which gets passed to consumers. The Labor Department’s January producer price index, for the record, sure enough showed big spikes in business spending on fuel.

What are some reasons—beyond Russian military machinations—might oil prices climb further? Marathon Oil said last week that its “exceptionally strong financial quarter” stems from higher energy prices and higher production, yes, but also “declining capex.” Its CEO declared: “I want to make clear that should commodity prices continue to surprise to the upside, we will remain disciplined and have no plans to allocate production growth capital.” Saudi Arabia and OPEC too, have restrained output despite tight global supplies. Demand for international travel is poised to revive. Capex (in other words, investment spending) is harder to justify amid pressure to cut carbon emissions.

Then again, oil prices can drop too, as they did sharply in 2008, 2014 and again (briefly) in 2020. Iran might soon be allowed to sell its oil in world markets again. The Fed’s tightening could cool demand. Marathon’s pledges aside, it’s hard for companies and countries to resist the temptation to produce and sell more oil with prices so high. And you know what they say about the oil market: The cure for high prices is high prices—remember when $130 oil helped pop the housing bubble in 2008, leading to demand destruction violent enough to bring oil prices down to just $30?

The Fed’s policymakers naturally discussed the oil threat at their January meeting, the transcript for which was published last week. Interestingly, they also mentioned the risk of further supply chain disruptions emanating from China, as well as concerns about “highly leveraged” nonbank institutions including hedge funds (one called Archegos blew up and caused a mild mess last year). Money market funds too, where many households and institutions keep their money for safe keeping, are at risk from sudden mass withdrawals—indeed, runs on money market funds were a key problem in the 2008-09 crisis (unlike bank deposits, money market deposits are not guaranteed by Uncle Sam). Still another run risk the Fed discussed: That from stablecoins, used to move money between government currencies and cryptocurrencies. USD Coin alone had a $53b market cap of Saturday, according to Coingecko.

So there’s your situational analysis: Consumers still spending heartily but oil and rate hikes menacing, with systemic financial risks under watch.

Most of Corporate America still seems content, and not just flourishing oil companies. US Foods had no problem “successfully passing on inflation to both contract and non-contract customers.” AutoNation expects “demand to continue to exceed supply well into 2022.” Corporate loan defaults remain low. Intel continues its aggressive investment with a foreign takeover bid. BJs, a California restaurant chain, is generating more revenue now than before Covid. In Silicon Valley, Cisco has a record backlog of business. Hyatt Hotels is seeing leisure bookings way ahead of 2019 levels. Can you sound any more bullish than JPMorgan Chase: “Everything that we’re seeing,” said its CFO last week, “is still super-bullish in general.”

In the meantime, 10-year Treasury yields are back under 2%, underscoring the trend of sharply rising shorter-term rates with longer-term rates calmer. One way to read that: Investors aren’t bullish on the economy longterm. Stock prices, seemingly entering a new era of bearishness as the Fed prepares to tighten, dropped again.

Just one more thing before moving on. The RAND Corporation published an astonishing study about the labor market, concluding that nearly two-thirds of all unemployed American males in their 30s have a record of arrest. Nearly half were convicted of a crime. Results differed only slightly by race or ethnicity. The question is: Are most of these men simply unemployable? Or might they help address the labor shortage if given the chance?

Companies

Walmart: Six decades ago, when Sam Walton opened a retail store in northwest Arkansas, nobody imagined it would one day become America’s largest company. By the 1990s, few imagined it could ever be challenged, with its unbeatable cost efficiency and controversial ability to crush all competitors big and small, from Sears and Kmart to the mom-and-pop shops dotting America’s Main Streets. Then along came Amazon, whose online retail prowess finally gave Walmart a credible scare. Had Walmart finally met its match? Was it destined to follow the path of Sears? The answer, it showed again last week, is an emphatic no. The company announced a $26b operating profit for the fiscal year that ended last month, on $573b in revenue. That’s roughly equivalent to the GDP of Sweden. Results for just the final quarter (covering November, December and January) were no less impressive, fueled by a strong holiday season, more in-store shoppers and improved inventories. Its sheer size and buying power enabled it to better navigate supply chain bottlenecks than most companies—it has the scale to charter its own ships from Asia, for example. What’s more, Walmart is successfully counter-challenging Amazon with its own fast-growing e-commerce business, selling not just its own products but creating an Amazon-like online marketplace for third-party sellers as well. It’s offering other firms fulfillment services too, including last-mile delivery for companies ranging from Home Depot to independent small businesses. Also like Amazon, Walmart is leveraging its busy website into a highly profitable online advertising platform that’s now a $1.2b business in its own right. Profits and revenue growth are strong across the globe, including key markets like China and Mexico. Walmart Plus, something akin to Amazon Prime, is just starting to gain traction. Sam’s Club, a Costco-like chain of warehouse stores, is performing well. Remember too that Walmart is a leading pharmacy, with big ambitions to provide a broader array of health care services. It’s likewise angling to provide more financial services. The bottom line: Walmart thrived during the pandemic, becoming 17% larger in terms of revenues and 31% larger in terms of operating profits. In the meantime, it expanded its percentage of online sales to 13%, more than double what it was pre-Covid. Its costs are rising to be sure, especially for labor. But it cites years of experience managing through inflation in regions like South America. Though demand remains strong, the outlook for consumer spending is highly uncertain this year. Walmart itself is confident, based on strong household balance sheets (high home values, low credit card debt, elevated savings, etc.). That said, measures of consumer confidence show great pessimism, with government stimulus measures finished and prices—gas prices, importantly—rapidly rising. Of course, Walmart, famous for its everyday low prices, is well-positioned to benefit from consumer distress. People still need food, medicines, auto parts and other essentials that Walmart sells, often cheaper than rivals. There’s still, of course, Amazon, now America’s second largest company by sales and employment. Looking beyond the present, the executive team in Arkansas has its eyes on emerging trends like social commerce, cryptocurrencies and shopping in the metaverse.

Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan shared his thoughts on the economy last week, presenting at an investor event hosted by Credit Suisse. Consumer spending in January, he said, was “very strong,” with ongoing strength into the first few weeks of February. What he sees, more specifically, are customers moving money out of their accounts to spend on various things. Spending on services like restaurant dining and travel is rising. People appear to be going back to work, based on the fact that childcare spending has now returned to pre-pandemic levels. In addition, customer account balances, rather than draining down as stimulus measures waned, have instead steadily increased since last summer. And that’s for lower-income customers with account balances below $5,000. Separately, Bank of America is making more loans to businesses. Moynihan sees U.S. GDP growing between 3.5% and 4% this year, “which ought to be good for our company.”

Tweet of the Week

Sectors

Automobiles: With vehicle production hobbled by the semicon shortage, is it any surprise that prices are skyrocketing? Edmunds, which provides research for car buyers, said 82% of all buyers in January paid above MSRP—that’s the manufacturer’s suggested retail price. One year ago, only 3% did. The year before that, the figure was less than 1%. More specifically, the average buyer paid $728 more than MSRP last month, compared to $2,152 below MSRP in January 2021. Cadillac, Land Rover and Kia are the brands seeing the highest levels of prices paid above MSRP. Alfa Romeo, Volvo and Lincoln, by contrast, are still being sold below. Automakers must love it, no? Actually, Ford and GM among others are demanding that dealers stop charging above MSRP, wary of alienating consumers. They are, after all, preparing several high-profile marketing campaigns to promote new electric vehicles. Dealers, however, are inclined to maximize revenues while supplies are so constrained. When will car prices finally drop? Edmunds isn’t optimistic: “Prices aren't expected to normalize for quite some time.”

Markets

Oil: Financial Times columnist Gillian Tett looks at why oil prices have increased so sharply, beyond the mere fact that supplies are limited. She points to a surge in robo-traders, which are automated computer programs (designed by investment firms) that buy and sell financial contracts tied to the future price of an asset. Well lately, there’s been a surge in robo-traders buying option contracts betting that oil prices will rise. And this can create a herd effect, driving up actual prices. Robo-trading, sometimes called algorithmic trading, is a growing phenomenon in financial markets, in this case impacting commodity markets. One implication is higher price volatility as buying and selling financial contracts occurs more frequently and (as mentioned) in herd-like fashion. “Fifteen years ago,” Tett writes, “oil prices moved from $54 a barrel for Brent contracts at the start of 2007 to $132 in July 2008—before collapsing to $40 in December that year, after the financial crisis. Today, a similar cycle might occur even faster due to automated trading, particularly if inflation fears undermine growth hope.” Javier Blas and Marcus Ashworth, writing on oil last week in Bloomberg, note: “The options market right now is signaling that, on balance, prices may be higher in the future, not lower.” To be clear, the price of future oil is currently cheaper than oil today—you can see prices for various delivery dates on the CME Group’s website (CME is the world’s leading exchange for buying and selling derivative contracts).

Venture Capital: In his new book about venture capital (“The Power Law”), journalist Sebastian Mallaby makes an important point about tangible versus intangible assets. Tangible assets are physical assets, like machinery or vehicles or real estate—something easily valued on a balance sheet. The value of intangible assets by contrast, is much harder for accountants to quantify—the value of Meta’s social network, for example, or the intellectual property behind Google’s online advertising algorithms. This distinction is one reason why traditional banks were unenthusiastic about financing tech companies—they’re simply harder to value with traditional accounting methods (they also don’t have hard collateral to repossess in the event of a loan default). So, as Mallaby describes, in stepped venture capital. In the Jan. 4, 2021 issue of Econ Weekly, we discussed the 2017 book “Capitalism Without Capital,” by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake. It’s all about the “intangible economy” in which companies invest heavily in things people can’t see, like software code, data-fed algorithms, branding and design. Think Google’s investments today versus U.S. Steel’s a century earlier. They similarly conclude that this intangible economy is much harder to measure.

Stocks: A quick stat from The Economist: Today, 53% of American households own company shares. In 1992, the figure was 37%. Also, the volume of shares traded in America today is 3.8 times what it was just a decade ago.

Government

Monetary Policy: The Fed has many critics right now, alleging it’s acted too slowly to address the current inflation scourge. Mohamed El-Erian, who once ran the investment firm Pimco, is among the most prominent. On the “Hidden Forces” podcast last week, he said the Fed has been way behind the curve in reacting to inflation. And now it must “hit the brakes very hard.” It should not, El-Erian argues, have adopted its new framework tolerating higher inflation for longer. It should not have labeled inflation transitory. And it should not have waited so long before ending its stimulative bond buying. He paints a picture of a U.S. economy that’s very different from the demand-starved stagnation of the 2010s. Today, the defining characteristic of the economy is not insufficient demand but insufficient supply, potentially made worse by a pause—or perhaps even reversal—in globalization. The transition to a greener economy is also proving more difficult than expected, contributing to strained energy supplies and a rise in prices.

El-Erian thinks investors became conditioned to believe that the Fed will support stock prices in any situation. Any time the stock market went down, it seemed, the Fed would step in with accommodative monetary policy. It was like a parent indulging a child with candy, he said, every time the child threw a tantrum. As a result, it made it almost foolish to not buy stocks and, voila: three years of incredible stock market returns.

He worries now: Can the highly-levered U.S. economy withstand a series of four or five rate hikes? Or will this cause a recession? In the meantime, expectations of ongoing inflation are taking root among households and businesses. The danger is if they start taking anticipatory reactions, i.e., workers demanding cost-of-living adjustments to their wages.

El-Erian also talked about geopolitical changes affecting the global economy. The world, he observes, is becoming more fragmented and less open. Many countries are having to choose between engaging with China or the U.S., which in Australia’s case led to a damaging decline in trade with China. The U.S. and Europe, meanwhile, still benefit from a post-World War II trading structure in which their currencies act as reserves, essentially meaning the U.S. and Europe provide paper money to the rest of the world in exchange for goods and services. They also have disproportionate influence at global economic institutions like the IMF and World Bank. And they manage most of the savings of the rest of the world (think Asians buying U.S. stock funds). But this arrangement won’t last forever.

Will it be Bitcoin or some other cryptocurrency that replaces the dollar as a global reserve currency? Never, El-Erian insists. If nothing else, governments will fight to ensure that never happens. That said, he thinks the cryptoeconomy will have an impact, in areas like payments and cross-border remittances.

There are, to be sure, plenty of high-profile economists who disagree with El-Erian about inflation’s menace. Some point to measures of inflation expectations and the fact that longterm bond yields, in contrast to short-term yields, are mostly flattish. That’s true for the U.S. Treasury market. It’s also true for the Eurodollar futures market, as Jeffrey Snider of Alhambra Investments vociferously emphasizes. He implores people to pay close attention to the giant Eurodollar market, where dollars are traded beyond U.S. borders. His takeaway from trends there: That global money supply, beyond the influence of the Fed, contracted greatly after the 2008-09 financial crisis and remains tight today.

Lobbying: For an insightful look at how companies and industries influence politics even at the local level, read ProPublica’s new report, undertaken in partnership with The Palm Beach Post, on the actions of Florida’s sugar industry. The state produces more than half of all U.S. cane sugar. But nearby residents complain of environmental pollution and health problems associated with burning cane. Here’s the link: https://projects.propublica.org/black-snow/ ProPublica, by the way, is trying to fill a void in local investigative reporting stemming from the strained economics of present-day media. The void removes an important watchdog on local corruption and influence.

Childcare: The pandemic exposed a glaring weakness in the U.S. economy: Its inability to deliver adequate and affordable childcare. And that’s shrinking the labor market as many parents feel compelled to stay at home rather than work. The Morning Brew’s Business Casual podcast spoke with Bloomberg’s Claire Suddath, who explains how childcare is a mostly private sector affair in the U.S., furnished by private companies without any major subsidies. But it is heavily regulated, which makes the microeconomics of such companies extremely difficult. Rules, for example, govern how many caregivers are required per child. And the ratio is especially stringent for infants. Inevitably, to have any chance at earning a profit, wages need to be low. Even so, profit margins across the childcare industry, Suddath says, average about 1%. And to earn even that, prices need to be high—she gave one anecdote of a mother who paid $45,000 per year for two kids. For many jobs, that’s an entire year’s salary. So it often makes sense not to work. The U.S. came close to having a government program for childcare. Congress passed one in the 1970s but President Nixon vetoed it. Today, according to Suddath, only about 40% of preschool age children go to preschool, among the lowest rates in the industrialized world. The bottom line: the economy isn’t producing enough childcare supply, driving prices out of the reach of many families. And that’s a problem for a country with a labor shortage.

Childcare: How to address the childcare shortage? One idea is lower regulations, but that carries risk. President Biden’s Build Back Better (BBB) plan, currently stalled in the Senate, would use federal money to boost pay for childcare workers and help low- and middle-income families pay for care at licensed facilities. But critics say the subsidies will greatly increase demand, further straining supply and further pushing up prices for the unsubsidized. The result could look something like the situation in housing, health care and higher education, where government financial assistance swells demand and lifts costs. As Vox explains, the BBB plan does also contain money for states to use toward increasing supply. But that would take time. Alas, as Vox concludes: “In the United States, in the years before kids are sent off to school, families are basically on their own in deciding what to do with them, in an economy and culture where both parents are increasingly expected to work.” Suddath calls childcare “the most broken business in America.”

Places:

Bentonville, Arkansas: One hundred years after the Civil War, in the 1960s, nearly half of all Arkansas residents were still living below the poverty line, more than double the national average. Today, the figure is closer to 15%, which still makes it the fifth poorest state by this measure, but only three points above the national average. Arkansas, so it happens, touches two of the most impoverished regions of the country: The Mississippi Delta in the southeast and the Ozark Mountains in the northwest. In between, meanwhile, are distressed economies like Pine Bluff, profiled in the June 21, 2021, issue of Econ Weekly—Pine Bluff was the fastest shrinking metro in the entire United States last decade. The Delta region, too, remains troubled, with poverty rates still roughly double the national average. The Ozarks, however, tell a much happier story. The state’s three main Ozark counties—Benton, Madison and Washington—have gone from having poverty rates roughly double the national average in 1960 to roughly equal to the national average today, according to the St. Louis Fed. A big reason is the University of Arkansas, located in the area’s largest city Fayetteville. Close to 30,000 students attend the school, a public institution. The greatest gains in wealth though, have occurred north of Fayetteville, in and near Benton County. There, three corporate giants loom large, giving the county itself a poverty rate that’s now lower than the national average. One of these giants is Tyson Foods, a poultry processor and retailer. Another is the trucking and logistics firm J.B. Hunt, also a Fortune 500 company. But neither come close in influence to Walmart, the single largest corporation in the country by sales—it’s the country’s largest private-sector employer as well. Northwest Arkansas wouldn’t be anyone’s first guess as the home of America’s largest company. But so it is. And so the retailer has delivered nothing short of an economic miracle to a once destitute region. Walmart, founded in Benton County 60 years ago by entrepreneur Sam Walton, has a global workforce exceeding 2m people today, 28,000 of them in the Fayetteville-Bentonville metro area. That doesn’t include another 10,000 or so employed by various Walmart suppliers with offices in the area. HUD Department figures show that Walmart, Tyson and the University of Arkansas alone account for 16% of all jobs in the metro area—a metro area that grew in population by 21% during the 2010s. Very few places in the country grew that fast. In fact, only 14 other metros did—most of them more familiar growth stories—Austin, Raleigh-Durham, Orlando and Boise, for example (also Midland-Odessa which Econ Weekly profiled last month). Remember, Pine Bluff, just a four-hour drive from Bentonville, was the fastest-shrinking metro last decade. A company the size of Walmart can indeed move mountains, even in the once-impoverished Ozark mountains. Last summer, the New York Times featured a story about Northwest Arkansas, highlighting its demographic changes. As recently as 1990, it was 95% white. Today the figure is more like 72% following an influx of immigrants taking jobs from processing chicken for Tyson to managing IT for Walmart. Springdale, home to Tyson, is now 38% Hispanic. Bentonville has a new Hindu temple. Labor Department data, by the way, showed a 16% y/y increase in average weekly wages in Benton County during the second quarter of 2019, before the pandemic put upward pressure on pay. No other large county in the country saw higher wage gains. But the pandemic exposed a major challenge. At a time of severe nationwide labor shortages, the extreme shortages of truck drivers and food processors are bedeviling Tyson and J.B. Hunt. It’s at companies like these where sharp declines in immigration hurt most. That said, all three of Benton County’s corporate giants are thriving financially, with Walmart announcing a $6b Q4 operating profit last week. The region, where housing prices are still relatively low, is attracting retirees as well. Walmart, meanwhile, is building a new headquarter campus, creating construction jobs. Things have come a long way since the federal housing department published an economic study of Northwest Arkansas in 1971. Poultry and the University were the twin pillars of the economy then. There was no mention of Walmart. (Sources: HUD, St. Louis Fed, US Census).

Davenport, Iowa, and Peoria, Illinois were the only two metro areas in the country to see a Q4 decline in median housing prices, the National Association of Realtors (NAR) said. NAR, by the way, is the country’s largest trade association, or to use the less flattering term, lobby group.

Alaska: Governor Mike Dunleavy, in his state of the state speech last month, spoke about Alaska’s Permanent Fund. What’s that? It’s essentially the state’s sovereign wealth fund, which reinvests the proceeds of Alaska’s bountiful oil wealth. In late January, the fund was worth more than $80b. Every year, all Alaska residents receive a dividend. Last year, the amount was $1,114, on top of the federal stimulus checks they received. Aside from high oil prices, last year’s strong stock market gains helped lift the value of Alaska’s pension funds, allowing it to erase big deficits. It’s also starting to see a comeback in its $4.5b tourism industry.

Utah, unlike Alaska, has water worries. Governor Spencer Cox, in his state of the state address, cited water as the “greatest limiting factor to our growth.”

Ohio: In another sign of a reviving Midwest, Bloomberg notes that Rickenbacker airport in Columbus saw international cargo arrivals up 73% last year. Columbus, remember, recently scored one of the biggest capital investments of all time courtesy of Intel.

Looking Back

Colonial America: You’ll remember the date 1776 from history class. It’s the year that America declared independence from Britain, a status they achieved by winning the Revolutionary War seven years later. But what did the American economy look like before the war? According to historian Thomas Middlekauf, in his book “Glorious Cause,” the 13 English colonies were home to just 250,000 people in 1700. That grew to 2.5m in 1770, with about 90% of the population living in rural farming areas. Seaport cities like Philadelphia, New York, Charleston, Baltimore, Newport (Rhode Island) and Salem (Massachusetts) were the exceptions. Much of the century pre-1776 saw expanding trade with Britain, involving exports like breads, meats, fish, lumber, iron, rice, tobacco, indigo and gunpowder. As a National Geographic map clearly shows, this was part of a triangular trade that also involved African slaves, though in the 1700s, the vast majority of slaves were shipped to the Caribbean and South America, not the 13 colonies. The colonies themselves sent food and other commodities to the Caribbean in exchange for items like sugar and molasses. Some slaves did come north as well, enough to make Africans the second largest group of colonials behind those hailing from Britain. The next largest group were Scots-Irish Protestants from Northern Ireland, typically settling in New England first but later moving south and west. Germans, many of them expert farmers, came in large numbers to Pennsylvania, residing alongside English Quakers. Dutch, Swedish and Jewish immigrants were also among the early settlers, followed later by Scottish Highlanders. All interacted, meanwhile, with the original settlers of the land, namely the Native Indian tribes along the eastern seaboard. A critical event in the history of pre-Revolutionary America was the Seven-Years War, sometimes called the French and Indian War. It was the first truly worldwide war, fought between Britain and France, with the colonists helping their mother country Britain. The conflict, from 1756 to 1763, generated a boom in demand for U.S. farm products. But that demand disappeared when the war finished, leading to economic hardship across the colonies. Britain too, faced financial strains from the war, amplified by having to defend all the new territory it had won in the Americas (including all former French territory east of the Mississippi River). London responded with new taxes on things like stamps and demands that colonists house and feed British soldiers. That didn’t go over well in the years leading up to 1776. And the rest is history.

Colonial America: One other point to emphasize from Middlekauf’s book: The different colonies didn’t have much in common leading up to the 1770s. Virginia and Massachusetts, for example, didn’t have any meaningful economic interaction with one another. Their trade was within their own colony and with Europe (primarily Britain) and the Caribbean. Colonies typically featured isolated economic systems, including that of the Hudson Valley in New York, dominated by feudal land barons.

Looking Ahead

Financial Stability: Have investors “overdosed on techno-optimism?” The Economist thinks the answer might be yes, with many investor portfolios “loaded up on ‘long-duration’ assets that yield profits only in the distant future.” The result is sky-high valuations of tech stocks, cryptoassets, electric carmakers and the like, which are now starting to tumble as interest rates rise. This leads to a more important question: Can the financial system safely absorb big losses? Or will major changes in the system since the 2008-09 financial crisis amplify the losses instead, leading to another big crisis? First of all, what are those changes to which The Economist refers?

One pertains to regulations, including capital rules that pushed a lot of risk-taking out of banks and into other areas of the economy. As the article points out, total borrowings and deposit-like liabilities of hedge funds, property trusts and money market funds have risen to 43% of GDP, from 32% a decade ago (and some of this debt is hidden; remember the Archehgos blow-up?). Non-bank entities, meanwhile, now account for about half of all mortgage lending (think Rocket Mortgage, now the country’s largest mortgage lender, ahead of even Wells Fargo and Bank of America).

Technology has changed too—more powerful computers conducting high-frequency algorithmic trading, for example, and new low-cost platforms for buying assets (think Robinhood). What would happen if everyone tried to sell their stock at the same time? What would happen if high-frequency traders sold all their Treasury bonds at the same time? Forget about the old bank runs of the past. The risk now is a run on an investment firm, or worse, on the Treasury market. A hint of the resulting chaos came during the GameStop affair of 2021, and the Treasury market selloff in 2020. In the latter case, the Federal Reserve had to step in as a market maker, or dealer, of last resort. All of this highlights risks in the current system pertaining to intermediating and settling transactions. The Economist writes: “ETFs, with $10 trillion of assets, rely on a few small market-making firms to ensure that the price of funds accurately tracks the underlying assets they own. Trillions of dollars of derivatives contracts are routed through five American clearing houses. Many transactions are executed by a new breed of middlemen, such as Citadel Securities. The Treasury market now depends on automated high-frequency trading firms to function.”

What’s also changed is the sheer volume of outstanding bonds, thanks to greater government borrowing and a preference among corporations to borrow via the bond market rather than from banks. And not only are there more bonds floating around, but they’re being traded—as are stocks—much more frequently than a decade ago. When the Covid crisis first hit in March 2020, BlackRock’s biggest investment-grade corporate-bond ETF traded 90,000 times a day. All that trading can create tons of price volatility and lead to runs on investment funds. “Markets operate at breakneck speed: the volume of shares traded in America is 3.8 times what it was a decade ago.”

The Economist concludes: “The financial system is in better shape than in 2008 when the reckless gamblers at Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers brought the world to a standstill. Make no mistake, though: it faces a stern test.”