Rate Adventure

Plus: This Week's Featured Place: Cheyenne, Wyoming

I have exciting news to share: You can now read Econ Weekly in the new Substack app for iPhone.

With the app, you’ll have a dedicated Inbox for my Substack and any others you subscribe to. New posts will never get lost in your email filters, or stuck in spam. Longer posts will never cut-off by your email app. Comments and rich media will all work seamlessly. Overall, it’s a big upgrade to the reading experience.

The Substack app is currently available for iOS. If you don’t have an Apple device, you can join the Android waitlist here.

photo courtesy of Visit Cheyenne

Issue 60: March 21, 2022

Inside this Issue:

Rate Adventure: The Tightening Era Begins

Quarter Point Order: But More Hikes Ahead, the Fed Said

Reaction to Powell’s Action: Stocks Jumped, Bonds Dumped

Oil Gains Blunted: But Still Over a Hundred

Signs of Softness: Retail Sales Show Hints of Slowing

Cyber Optic: Consulting Firm Gartner Sees Scary Things Ahead

A Dance with France: Remembering the Franco-American Alliance

And This Week’s Featured Place: Cheyenne, Wyoming, Missile Muscle

Quote of the Week

“Now, we always also said that once that gas price reaches over $4 a gallon, which it has now, that we normally see the consumers stay closer to home.”

-Dollar General CEO Todd Vasos

Market QuickLook

The Latest

And there you have it. The Federal Reserve’s policymakers, at their much-anticipated meeting last week, raised interest rates for the first time since 2018. The increase was just a quarter of a point, from levels near zero. But it marks the first step toward reversing heavy monetary support for the economy—an economy that suffered a near-meltdown when the Covid crisis first struck in March 2020. Since then, the U.S. economy has come roaring back, with nearly 6% GDP growth last year, plus a job market that’s hotter than hot. Maybe too hot, in fact, leading to levels of inflation not seen since the late Carter/early Reagan years. Consumer prices are 8% higher than they were a year ago. Producer prices are 10% higher. No wonder why the Fed feels it’s time to cool things off a bit by making loans more expensive.

But just a quarter point? Some economists say it’s not enough. Some, instead, say anything more hawkish would be dangerous in the face of growing headwinds, notably rising crude and food prices. Higher interest rates themselves can prove toxic to an economy, and in this case—the doves argue—won’t do much anyhow to quell the kind of inflation now raging; in other words, inflation stemming not from too much money or too much demand but constrained supply (not enough workers, not enough semicons, not enough port capacity, etc.).

In fact, the Fed itself seems to agree with the hawks. Yes, it hiked by just a quarter point. But members of the policy committee now project the federal funds rate (more on this in a second) to reach 2.8% next year. That implies a lot more hiking in the months ahead. Chair Jay Powell amplified the hawkishness by announcing a readiness to commence “quantitative tightening” as early as their next meeting in early May. This means shrinking the giant pile of government and agency bonds it amassed while conducting “quantitative easing” throughout the pandemic.

Powell characterized the economy as “very strong,” with extremely tight labor markets and inflation running well above the Fed’s long run goal of 2%. GDP, he said, should increase 2.8% this year, still rather bullish if not quite as sizzling as last year’s 5.5% growth. The health of household and business balance sheets—along with the red-hot job market—form the bedrock of the current economic strength. But high levels of uncertainty remain, he admits, amid geopolitical tensions, “subdued” labor supply, high energy prices and bottlenecked supply chains made worse in recent weeks by Covid outbreaks abroad, particularly in China (ask Apple about that). Powell’s bottom line: The probability of a recession is low, but the risk of inflation causing unhealthy outcomes is growing. Hence the readiness to tighten rather aggressively in the months ahead.

To clarify, when the Fed “raises rates,” what it’s specifically doing is setting a target for what financial institutions charge each other for overnight loans—that’s the Federal Funds rate, hovering below 0.10% throughout the pandemic but reaching 0.33% as of Thursday (the day after Powell’s press conference). The rate was 1.10% just before the crisis. How exactly does the Fed influence the overnight rate? If you really want to know, here’s a good explanation: https://www.stlouisfed.org/open-vault/2020/august/how-does-fed-influence-interest-rates-using-new-tools#:~:text=The%20Fed%20uses%20its%20monetary,reserves%20in%20the%20banking%20system.

The idea, anyway, is that if rates for overnight lending go up, then rates for longer-term lending will go up as well. That’s been happening, but with an important caveat: Shorter-term rates—what the U.S. government is paying to borrow for two or three years, for example—have risen much more sharply than longer-term rates. In fact, it currently costs more for Uncle Sam to borrow for three years than it does for ten, a counterintuitive inversion that’s historically foreshowed recessions. One interpretation is that large portions of the market prefer to buy safe longterm Treasury bonds right now, rather than lend for more productive, GDP-enhancing purposes. Others disagree, saying longterm rates are suppressed not because of anemic animal spirits but rather large bond buying by the Fed and fellow central banks, along with other actors merely stuffing themselves with safe assets to comply with regulations. Still others attribute low longterm rates to demographic factors, growing wealth inequality or low productivity in sectors like housing, health care and higher education (the infamous Three H’s).

One critical category of longterm interest rates now rising: Home mortgage rates, typically for 30-year loans, which now top 4% on average, according to Freddie Mac. This upward drift contributed to a 7% decline in existing home sales from January to February, says the National Association of Realtors. Demand, you can see, is clearly softening. But to be clear, most housing economists see home prices continuing to rise this year given extremely tight supply. The homebuilder Lennar, for its part, said last week that the housing market remains “very strong in all of our major markets (see the Sectors section below),” never mind a “supply chain that is all but broken,” plus “a workforce that is short in supply, and the intense competition for scarce and titled land assets.” Sadly under these supply-constrained conditions, 87.5m households are currently unable to afford a median priced new home, says the National Association of Homebuilders.

Turning to commodity markets, extreme volatility continued, with oil prices dropping sharply though still ending the week north of $100 per barrel. Stocks reacted well to the Fed’s bullish pronouncements. Treasury yields rose. One reason for oil’s decline, by the way, is mounting distress in the Chinese economy, now facing higher energy costs, a deflating real estate bubble, sluggish household demand, a worrisome reliance on exports (especially to the U.S.) and Covid lockdowns in key production centers. Don’t forget: the U.S. imported $506b worth of goods and services from China last year. $506b!

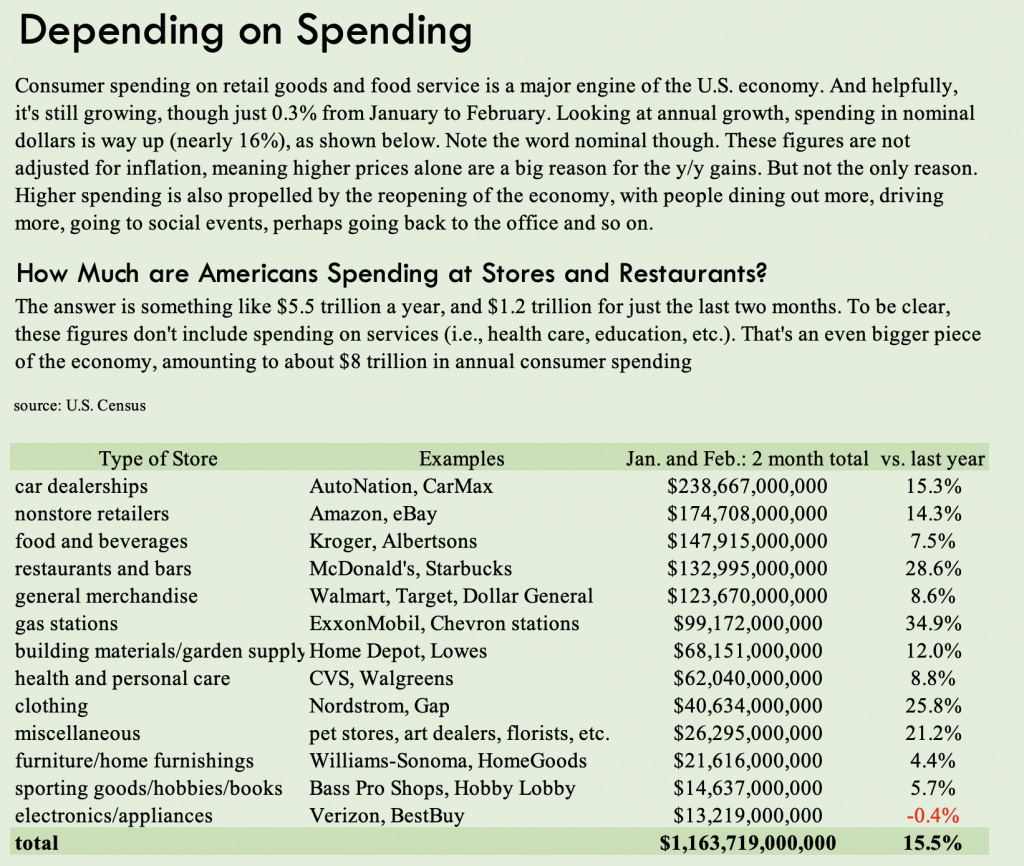

That makes China, for one, keen on updates about the American consumer? So how’s she doing? The Census published data on U.S. retail sales for February, which rose slightly from January, after much bigger gains a month earlier (they actually declined in February if you exclude spending at gas stations). The retail sales figures are not adjusted for inflation, meaning rising sales partly reflects people paying more for the same stuff, rather than buying more stuff. View the chart below for more detail. But the key takeaway is that consumer spending shows some signs of cooling off.

Some updates from Corporate America: Elon Musk says Tesla and Space X both face disruptive inflation. Costco, Kroger, BJ’s and Walmart’s Sam’s Club, the Wall Street Journal reports, each get about 10% of their revenue from gasoline sales. Dollar General says Americans stay closer to home when gas prices exceed $4 a gallon. It also says the economic health of its mostly low-income customers depends most importantly on the job market, i.e., “whether they’re gainfully employed or not.” Dollar General believes, incidentally, that inflation helps its business by encouraging people to “trade down” from higher-priced stores. Walmart, perhaps in a similar position, plans to hire more than 50,000 additional workers, including tech professionals at newly established offices in Atlanta and Toronto. HCA, the giant hospital chain, says it’s beyond the Omicron surge. The Atlanta-based railroad Norfolk Southern, meanwhile, sees the auto crunch easing as semicon availability improves. “We’re seeing less and less [disruption] every week.”

And this week: Jay Powell will be heard from again, heading a high-powered list of speakers scheduled to address an annual economic policy conference (hosted by the National Association for Business Economics, or NABE). Other speakers include Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic, the head of President Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers Cecilia Rouse and Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman. The ghost of Paul Volcker will be at the conference as well.

Companies

Vail Resorts: For most companies dependent on tourism, including many airlines and hotels, summertime is peak season. Not for Vali Resorts. All but a few of its 37 mountain resorts—six of them in Colorado—peak during the winter months. They’re chief activity, after all, is skiing. The firm does own a few resorts in Australia, where ski season coincides with America’s summer. But still, Vail Resorts is a winter-centric company, generating a large majority of its revenues between mid-November and mid-April. Unfortunately, this past ski season was marred by severe staffing shortages, especially during Covid’s Omicron wave in December and January. Labor availability has since improved, accompanied by better snowfall. But the 2021/22 ski season will soon end. The company has a big presence in Breckenridge, Colorado, the most visited mountain resort in the U.S. Naturally, its namesake city Vail is another one of its big markets. It owns resorts in the eastern U.S. too, earning money from entry passes, lift tickets, dining, retail, ski instruction, lodging, etc. During summers, its resorts offer activities like mountain biking and hiking, but these draw far fewer visitors than the winter sports. Let’s end with some fun facts: Europe is the largest ski market in the world, triple the size of North America’s in terms of visitations. And in terms of U.S. states, California gets the largest number of tourist arrivals, followed by Florida, Nevada, Texas and New York.

Tweet of the Week

Sectors

Housing: The homebuilder Lennar, in its earnings call last week, gave an assessment of housing markets by geography. Florida, it said, is benefitting from local demand as well as in-migration from the northeast, midwest and west coast. Texas is the country’s strongest housing market for Lennar, and Austin its strongest market within Texas—people are moving to the Lone Star State from both east and west. The Carolinas are hot. Same for Atlanta and Huntsville. Colorado is attracting buyers from other states thanks to strong job growth. Phoenix and Las Vegas continue to be “two of the hottest markets in the country,” benefiting from “business-friendly environments, real job growth and immigration from California.” California itself remains “very strong” as the state’s severe housing shortage means more demand than supply even with heavy out-migration. Specific California areas of strength include the Inland Empire, Sacramento and East Bay of San Francisco. The Pacific Northwest, which includes the roaring economies of Seattle and Portland, continues to be a strong market, “as significant land use and development restrictions limit production to meet growing demand.”

Energy: EPC Power, a San Diego-based manufacturer of energy storage systems—and producer of a podcast called the “Energy Gang”—presented its top five energy developments of 2021. Topping the list was the Texas “freeze wave” that disrupted power and proved a wake-up call to Americans about the questionable resiliency of their energy systems. Another big event was the activist shareholder victory at ExxonMobil, long reluctant to accept the realities of climate change. “Green stimulus” also made an important impact last year, specifically all the new government money allocated to address climate change. EPC cited the large number of company, industry and government commitments to net zero carbon emissions—even Saudi Arabia was among them. And finally, the top five list included major advancements in battery storage, with costs falling and supply increasing.

Airlines: At a JP Morgan investor event last week, the country's largest airlines sounded exceptionally bullish. Delta, for its part, said it's never "seen demand turn on so quickly as it has after Omicron.” Demand is so strong, in fact, that most airlines feel confident about passing along the recent rise in fuel prices. Delta again: "We are very, very confident of our ability to recapture over 100% of the fuel price run-up in the second quarter." Transatlantic bookings have softened since the Ukraine invasion, however. On the other hand, American Airlines said domestic leisure demand has been higher than it's ever been, adding that "we don't have as many airplanes as we want." But business demand is bouncing back "very quickly" too, says United. Note that U.S. airlines also collect large sums of revenue by selling frequent flier program points to banks, which use them to entice new credit card customers. And sure enough, credit card revenues are strengthening for airlines, in Southwest's case coming in "stronger than anticipated."

Digital Advertising: Alphabet and Meta, better known as Google and Facebook, are the kings of online ads. But don’t forget about Amazon, with $30b in ad revenues, and Apple, with perhaps $5b, according to analyst estimates. Even Walmart, with its growing online presence, generated more than $2b in advertising revenues last year. Still, these figures pale compared to Google’s roughly $250b in annual ad revenues, and Facebook’s $110b. For Google, these revenues mostly come from online searches, which is “the best and most profitable form of advertising,” according to Stratechery, a newsletter by Ben Thompson. He writes: “Google doesn’t have to figure out what you are interested in because you do the company the favor of telling it by searching for it. The odds that you want a hotel in San Francisco are rather high if you search for ‘San Francisco hotels’; it’s the same thing with life insurance or car mechanics or e-commerce.” Meta/Facebook’s ad model is different, based not on search but on assigning a unique identifier to each of its users gleaned the mobile device they’re using. When a user clicks on an ad and ultimately buys something, that’s information useful to advertisers. Or as Thompson writes: “Advertisers take out new ads on Facebook asking the company to find users who are similar to users who have purchased from them before.” More recently though, Apple’s new privacy rules make it difficult for Meta to collect information on users that download the Facebook or Instagram apps from the Apple App Store.

Markets

Short-Term Credit: The Economist featured a story about the resiliency of credit markets in the U.S. and other developed markets, giving praise to financial reforms enacted after the 2008-09 crisis. “Credit is the financial system’s oxygen supply,” it writes. When suddenly unavailable during the crisis of 2008 (banks stopped lending to each other), Lehman Brothers collapsed, “and a subprime mortgage crunch turned into a global financial crisis.” Once again in 2022, with Russia’s war on Ukraine causing unease, financial actors are curtailing riskier lending, preferring safe assets instead. That usually means, most importantly, scrambling to own U.S. dollars and U.S. Treasury bonds. “A rush into American government debt—the safest asset of all—has pushed Treasury yields down even as inflation expectations have risen.” Lenders, the Economist adds, are “prizing security over returns.” What’s wrong with that? For countries outside the U.S., borrowing in dollars has suddenly become more expensive. For U.S, companies that earn a lot of their revenue abroad (think IBM or GE), depreciating foreign currency means lower income. But more importantly, a rush to safe assets presents risks to short-term money markets, in other words, markets to borrow and lend money for just a day or two, or just a month or two. It’s a giant but often overlooked part of the financial system (sometimes called its plumbing), on which banks, companies and other economic actors depend to ensure they have enough cash to operate each day. Overnight borrowing and lending also ensure the smooth functioning of payments moving between different parties, including banks settling who owes what to each other at the end of every day. Unfortunately, things might not go smoothly when everyone is demanding safe assets like Treasuries at the same time (or put another way, when everyone wants to lend to Uncle Sam at the same time). That’s what happened in 2008 when banks stopped trusting each other, and thus stopped lending to each other, preferring to make short-term loans to the Treasury instead. Things nearly got worse in March 2020 when people didn’t even think Treasuries were safe enough—the Fed quickly stepped in with a firehose of liquidity. Is there another jolt to short-term money markets now underway? No, The Economist reports, thanks to past central bank actions. The Federal Reserve, for one, introduced huge amounts of reserves, which are a form of money available to Fed member banks. It’s also introduced programs to ensure access to dollars for institutions that are not. banks belonging to the Federal Reserve system. Money market funds, for example, can now borrow directly from the Fed as well. Foreign central banks, furthermore, now have access to dollar swap lines, protecting against a destabilizing dollar shortage abroad (most of the international economy operates on dollars). The Fed has also provided guarantees to the repo market, where trillions of dollars are borrowed and lent overnight (using Treasuries as collateral). Thanks to this large repo market, The Economist explains, banks and other financial institutions no longer need to rely so much on direct lending to each other. The repo loans are collateralized, which is safer, but it means heavy demand for collateral, contributing to a shortage.

Long-Term Credit: What about the current health of longer-term lending? The Economist article had something to say about that as well. “Longer-term credit conditions are also weathering the storm remarkably well,” it writes. Even very risky companies, whose bonds are often called “junk,” are still trading at yields that aren’t much above safe asset yields. One reason, according to Lotfi Karoui of Goldman Sachs, is that “a fifth of the $1.6 trillion American high-yield bond market is issued by oil, metals and mining firms that are benefiting from—not hurt by—ballooning commodity prices.

Places:

Cheyenne, Wyoming: Sixty years ago, as the Cuban Missile Crisis threatened humanity’s existence, President John F. Kennedy thankfully decided not to fire. But if he did, a group of highly-trained U.S. Air Force personnel in Wyoming was ready. In 2022, the U.S. and Russia are again adversaries, and once again, there’s unnerving talk about usage of nuclear weapons. Also once again, the folks in Wyoming are ready. Just in case. Cheyenne, Wyoming, specifically, is home to the F.E. Warren Air Force Base, a critical node in America’s nuclear defense. It’s one of three bases—the others are in North Dakota and Montana—equipped with underground silos capable of firing nuclear-armed Minutemen III ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles). The base also happens to be central to Cheyenne’s economy, alongside state government. Wyoming, as it happens, is a relatively young state, and today the least populous of any state. Like many cities of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains, it owes its existence to the first transcontinental railroad, completed in 1869. Two years earlier, the Union Pacific railroad chose present-day Cheyenne as a base of operations, roughly 1,000 miles west of Chicago and 1,000 miles east of San Francisco. A U.S. army base—on the site of what’s today the Air Force base—was established there as well. When Wyoming became a state, Cheyenne became its capital. The “Cowboy and Indian” culture of American lore soon developed, tied to the cattle trade. Cheyenne was briefly a major airline hub in the early days of aviation. Today, Wyoming is the country’s largest coal producer thanks to reserves in the Powder River Basin. Alongside agriculture and energy is tourism, the third leg of the state’s economy today. Wyoming is, after all, home to Yellowstone National Park, not to mention Jackson Hole, an affluent resort that hosts an important Federal Reserve event each summer. Grand Teton National Park is in Wyoming as well. But these sites are in the mountainous northwest corner of the state. Cheyenne, in the southeast corner, is in flat country, lacking any natural wonders to attract tourists. Instead, it lures them with its cowboy and Native American culture, celebrated each year at Frontier Days, a ten-day event that attracted 550,000 people last summer—the event was canceled the year before due to Covid. The University of Wyoming, in nearby Laramie, also has a major impact on the Cheyenne economy. Health care facilities, public schools and retailers like Walmart are major employers. So still, incidentally, is Union Pacific. Hardly just focused on its railroading past, however, Wyoming, including Cheyenne, is now trying to become a hub for the crypto-economy. Favorable laws and regulations are attracting crypto organizations like Kraken (an exchange), Cardano (a smart contract platform) and Ripple Labs (payment solutions). That’s controversial in some circles, but not as controversial as the state’s financial secrecy laws, allegedly making it a haven for tax avoidance. This came to light with the Pandora Papers, a collection of leaked documents that prompted the Washington Post to write an article entitled: “The ‘Cowboy Cocktail’: How Wyoming Became One of the World’s Top Tax Havens.” (For more on tax havens see Econ Weekly: May 3, 2021). For all its financial ambitions, military might and clout in state politics, Cheyenne remains a small city with just 100,000 people in the metro area—roughly 15,000 are associated with the Air Force base, including military retirees and their families. That 100,000 figure makes it about the same size as Grand Forks, North Dakota, or Hot Springs, Arkansas. Its population did grow a healthy 8% during the 2010s, boosted by the residual impact of Denver’s mega-boom just an hour-and-a-half to the south. Between Denver and Cheyenne is Fort Collins, Colorado, where population rose a scorching 19% last decade. Will the growth continue to bleed north and ultimately turn Cheyenne into a boom town? Not having an attractive mountain landscape like Denver or Jackson Hole hurts. Housing prices have nevertheless been rising sharply, though that’s been true almost everywhere during the pandemic. The current jump in energy and ag prices certainly helps Wyoming. The state is one of nine without an income tax, which can be both a magnet for new residents but an obstacle to development projects, including plans to revitalize downtowns, improve broadband access or attract new air service. Of course, Wyoming’s distaste for government taxing and spending belies Cheyenne’s economic dependence on federal military dollars and state government. As for Warren Air Force base, the military originally armed it with ICBMs in the 1950s because of its location in the center of the country yet far enough north to strike the Soviet Union over the North Pole. The Soviet Union is gone, but the missiles remain, ready again to defend the U.S... just in case. (Sources: U.S. Census, US HUD, Roger Coupal of the University of Wyoming, Wyoming Economic Development Association, Cheyenne Leads and Wyoming PBS, which produced this interesting profile:

The Nuclear Triad: Warren Air Force base in Cheyenne is one of three places where the U.S. military stations its Minuteman III ICBMs (397 in total). The two other sites are Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana and Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota. But keep in mind, America has a three-pronged nuclear force, called the Triad. Nuclear weapons are launched not just from underground missile silos but also from Trident submarines (14 of them) and aerial bombers (76 B-52s and 20 B-2s). The subs are based in Bangor near Seattle and Kings Bay north of Jacksonville, FL. The B-52s are based at Barksdale near Shreveport, LA, and Minot in ND. The B-2s are at Whiteman base in central Missouri.

Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation: Don’t confuse Cheyenne, Wyoming’s capital, with the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation, which is located within Montana. It’s home to about 5,000 people, with an economy that depends mostly on federal and tribal government, along with public services like schools and utilities. Farming, ranching, textiles and construction are present as well. But according to the Minneapolis Fed, only 14% of residents (and just 8% of male residents) have a college degree. Less than half of households have broadband access. The unemployment rate is 27%. As on many Indian reservations, alcohol and drug abuse are all too common. So are suicides. The reservation does, however, sit on one of the richest coal deposits in the country, as described in a 2017 story on National Public Radio. But as the piece described: “Despite high unemployment and systemic poverty, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe has never touched the coal.” It’s a controversial topic, with some eager to tap the economic benefits and others seeking to protect the land and environment.

Looking Back

The Franco-American Alliance of 1778: Would the United States exist today were it not for France’s help against Britain in the Revolutionary War? Surely not. A program on Britain’s BBC, “In Our Time with Melvyn Bragg,” gathered a group of U.K.-based historians to discuss the origins of the early relationship between the Americans and French. Frank Cogliano (University of Edinburgh), Kathleen Burk (University College London) and Michael Rapport (University of Glasgow) begin their discussion with the Seven Years’ War (1756 to 1763), also called the French and Indian War. Britain (supported by its American colonists) defeated France (supported by various American Indian tribes). There was no longer any question now about which country was the world’s most powerful: It was Britain, not France. The victory was costly, however, and so was maintaining a North American troop presence to defend all that newly-won territory. London wanted the American colonists to help pay for it. No thank you, said the Americans, separately upset at the British for blocking them from settling in Indian Territory (in what’s today the midwest and Appalachia). No taxation, the colonists insisted, without representation in Britain’s parliament. Britain insisted: A Stamp tax in 1765. That same year: a demand that colonists house and feed its soldiers. More taxes in 1767. Colonists reacted with boycotts of British imports. Tensions came to a boil, leading to episodes of history known to every American schoolchild: The Boston Massacre (1770), the Boston Tea Party (1773) and a Declaration of Independence (1776). By then, war was already raging, but France wasn’t yet ready to intervene. The British, after all, were heavily favored—until that is, the American victory in the Battle of Saratoga (1777). Now the French were ready to help. Revenge, however, wasn’t their only motivation. Economics played a part too. As the panel of historians explains, the Seven Years’ War left France with heavy debts. And one way to generate more income to repay those debts was supplanting Britain as the main trading partner with the Americas. Thus was born the Franco-American alliance in 1778, negotiated by Benjamin Franklin in Paris. It provided the Americans with both economic and military aid that would prove decisive. Suddenly, the British Navy and Army had to defend their far-flung overseas possessions from French attack. These included India. They also included the Caribbean, at the time an extremely lucrative source of trading revenue for Europe (think slave-based sugar plantations). Sure enough, London redeployed ships and soldiers away from the American theatre, ultimately leading to defeat at Yorktown and recognition of American independence (1783). As for France, things didn’t quite unfold as planned. The American struggle wound up encouraging a revolution at home, one that would eventually lead to the rise of Napoleon. It was Napoleon, in fact, who sold the Louisiana Territory to Thomas Jefferson in 1803. The early 1800s would also see the young United States divided between sympathies for Britain and France, at times leading to heightened tensions between America and its former ally.

Looking Ahead

Cybersecurity: Sorry to be so morose, but cybersecurity risks are getting scarier and scarier. They might even become lethal. Gartner, which provides information and consulting services, estimates that by 2025, attackers will have weaponized a critical infrastructure system that can harm or kill humans. Yikes. In fact, the risk is already a reality. In 2020, a woman in Germany died while her ambulance was forced to take her to a more distant hospital because the closer one was hit by a major ransomware attack and unable to take new patients. It’s not just hospitals that have to worry. As Gartner points out, critical infrastructure also includes energy production and transmission, water and wastewater treatment, and food and agriculture.