Pricier Crude, Pricier Food

PLUS: This Week's Featured Place: Tri-Cities, Washington

Issue 58: March 7, 2022

Inside this Issue:

Pricier Food, Pricier Crude: World Facing Commodity Catastrophe

Job Market Rocket: More Evidence of Explosively Strong Labor Demand

Will Oil Spoil the Boom? WTI Spikes 26% in One Week

Powell Comes Clean: “Inclined” to Raise Rates a Quarter Point

Dwelling Dilemma: Wise or Unwise to Help Prices Rise?

Meta’s Metaverse Mindset: Zuckerberg Speaks

French Fried: Extreme Heat Causing Potato Farm Harm

Mankind’s Bind: Clock Ticks as Climate Change Afflicts

And This Week’s Featured Place: Tri-Cities, Washington, Waste Odyssey

Quote of the Week

“When I was growing up, we had the military industrial complex. Now we have the health care industrial complex.”

-North Carolina State Treasurer Dale Folwell, speaking on the “Bond Buyer” podcast

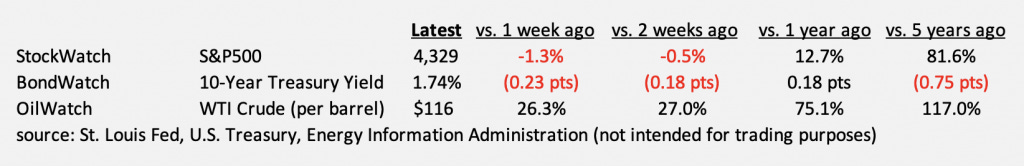

Market QuickLook

The Latest

The global economy faces a new test as Russia assaults its neighbor, and as other countries respond with crippling sanctions. At stake are vital supplies of energy, agriculture and other commodities. And sure enough, costs are skyrocketing. Pricier food, in other words, and pricier crude.

Last week, oil prices (WTI) jumped an astonishing 26%, reaching $116 per barrel. In nominal terms anyway, that’s higher than they ever went during the early 2010s. In fact, they haven’t been that high since the summer of 2008. For the U.S., remember, the early 2010s was a time of frustratingly sluggish economic growth. The summer of 2008, recall, was the final moment of calm before the ruinous housing and financial collapse symbolized by the fall of Lehman Brothers. For Americans, indeed, spiking oil prices go hand in hand with the worst of times.

Yet in other ways, it feels like the best of times. Another spectacular jobs report makes clear that America’s economy is firing on all cylinders, except ironically enough, in the area associated with cylinders—the auto sector lost 18,000 jobs in February. But don’t dwell on that (it’s a semiconductor thing). More importantly, the economy created 678,000 new jobs in February, following revised totals of 481,000 in January and 578,000 in December. Rarely if ever has there been such torrid job creation. Still though, the total number of people working in America remains 2.1m fewer than just before the pandemic. Labor participation, though trending up in recent months, is still down from pre-pandemic times. For seniors, many opting for earlier retirement, participation is down by more than two full points.

To put it mildly, demand for labor exceeds supply, which explains why hourly pay is up 5% y/y, and up 11% from two years ago. Gains are higher still for lower-income workers. Inflation, of course, means most workers are at best seeing their spending power hold steady. With gas prices spiking, many more will see inflation-adjusted incomes decline. And that in turn threatens the engine of America’s economy: consumer spending. So far, it’s held up well, as one would expect given such robust hiring. But inflation’s impact on real incomes casts an ominous shadow.

Enter the Fed, now just a week and a half away from its greatly anticipated decision on interest rates. In fact, there’s not much suspense anymore. Jay Powell, testifying to Congress last week, openly stated his preference for a quarter point hike—he’ll make his announcement on March 16th. The Fed, he said, will also proceed with plans for shrinking its portfolio of assets (it purchased massive quantities of bonds during the past two years). But he emphasized that high levels of economic uncertainty make it imperative to be flexible, responding to events and developments as they occur. Powell spoke of an “extremely tight” labor market made worse by lower immigration. He admits that monetary policy can’t do much to unclog supply chains. But he still expects inflation to ease as supply chains organically loosen, and as demand cools following last year’s stimulus-fueled growth. To those who look to longterm bond markets for inflation signals, stubbornly low yields are clear: Inflation will not be a longterm problem. Plenty of others disagree.

No one will disagree that geopolitical conditions have turned for the worse in recent weeks. As the U.N. reminded last week, grave threats from climate change loom large over civilization’s future. But mercifully, the long pandemic nightmare (fingers crossed) seems finally to have passed, with U.S. cases sharply down and health restrictions eased. The economic impacts of Covid-19 may linger, however, with supply chains still strained by ongoing Covid troubles abroad, most importantly East Asia. The pandemic of course, brought many changes to the U.S. economy, from remote working to—perhaps—an enduring re-shoring of domestic production. That’s to speak nothing of other emerging economic themes of the 2020s, including the transition to electric cars. There’s the transition to green energy as well, an endeavor proving more difficult and costly than many expected.

To understand how hydrocarbons shaped the modern world, there’s no better read than Daniel Yergin’s history “The Prize.” Oil, it makes clear, greatly influenced the outcomes of World War I, World War II, the Cold War and everything in between. Today, oil’s influence is no less visible in the policies of not just Russia but OPEC and Texas shale producers. OPEC and Russia, incidentally, decided against boosting output last week, with Saudi Arabia reportedly seeking policy concessions from the U.S. in return. One of its concerns: What appears to be an imminent agreement that would allow Saudi Arabia’s regional rival Iran to export more of its oil. Importantly, international sanctions applied to Russia exclude oil exports, though there’s talk in Congress of changing that (imagine what that would do to oil prices).

Back on the U.S. earnings circuit, Q4 reporting season is nearing an end, with just a few more heavy hitters yet to report—Oracle for one will present this week. Last week, Target, Costco, Salesforce, Kroger, BestBuy and Zoom were some familiar names taking center stage. Ford made big news by announcing separate divisions for its electric and ICE vehicles. Boeing’s largest supplier Spirit AeroSystems (not to be confused with Spirit Airlines) spoke of exposure to Russian titanium, important for building airplanes. Others including Apple and Visa took steps to withdraw from Russia’s market.

In the meantime, a labor dispute will delay the start of Major League Baseball season, having already cost Florida and Arizona big tourist dollars. Eyes are on global dollar demand, for now manageable but often a source of instability in times of economic and geopolitical stress (see March 2020 for a case study). Stocks continue to falter. But not all stocks—ExxonMobil’s shares are up nearly 40% this year. Occidental Petroleum’s have nearly doubled, prompting Berkshire Hathaway to raise its stake. Berkshire’s railroad BNSF, incidentally, seems well-positioned as coal demand soars, trucker fuel inflation soars and American industrial investments soar—railroads like Union Pacific, CSX and Norfolk Southern saw big share gains last week.

This week, all eyes turn to the February consumer price index (CPI). Will it show any signs of moderating inflation?

And one final word on Russia’s economy: As Colombia University’s Adam Tooze wrote in his “Chartbook” newsletter on Substack: “Like most folks, I’ve been staggered by how rapidly the West has escalated the economic war against Putin’s regime. But, we must remind ourselves that energy remains the giant exception.” Indeed, at the start of this year, he writes, citing Bloomberg’s Javier Blas, Russia was earning $350m per day from oil and $200m per day from gas. On March 3, Europe alone paid $720m to Russia—just for gas.

Companies

Meta: He’s one of America’s most successful but controversial business leaders: Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg. And he’s just spoken to podcaster Lex Fridman for two hours, sharing his thoughts on everything from the metaverse to online cyber-bullying. His decision to change the company’s name from Facebook to Meta, for one, underscores the big bet the firm is making on virtual and augmented reality, technologies Zuckerberg hopes will lead to more immersive online experiences. The current online experience involves mostly just looking at a screen, he says. In the future, it will be more three-dimensional, with things you can smell and feel. Developing this won’t be easy though, requiring advances in tracking facial and eye movements, mapping out brain activity and better understanding human psychology. The overarching idea: “to make computing more natural.” Already, Zuckerberg points out, many of the most important moments of peoples’ lives are happening in the digital world. That trend will only grow as the metaverse unfolds, offering new ways to play games, interact with friends and improve work productivity. One potential use case is enhancing personal fitness through immersive applications. He expects a large economy to develop across the metaverse, catering to people’s digital selves—one potential market is designing digital clothing for people to wear during their next video chat with friends or co-workers.

But what about security in the metaverse? Imagine a hacker stealing your online identity and impersonating you at a work meeting. Will the online “you” be a representative avatar of yourself or a photorealistic version? Will the metaverse further aggravate online ills like cyber bullying, spreading misinformation, political polarization and election manipulation? Zuckerberg rejects the premise that Facebook and social media are responsible for such ills. But he acknowledges the need to combat them, with help from artificial intelligence. Biometrics, meanwhile, can help with securing people’s identity in the metaverse.

Zuckerberg makes no apology for running an advertising business, arguing that ads are what allows its products to be free for users (he often contrasts this with Apple’s model, which he says only benefits people with the money to afford its expensive products). The conversation touched on other controversies as well, like whether Facebook’s algorithms intentionally favor content that makes people angry to get them more engaged—not true, he says, while admitting that company profits rise in tandem with more users and more engagement. He surely does have a point in asserting the impossibility of pleasing everyone. Some argue Meta needs to do more to cleanse the content people see, removing fake news, for example, from anti-vaxers, hate groups and foreign governments, for example. Others argue no less vociferously that it censors too much.

Lamb-Weston is based in Eagle, Idaho. But it’s the largest non-government employer in Tri-Cities, Washington, this week’s featured place (see below). What does it do? It “sees possibilities in potatoes,” a poetic way of saying it sells french fries and other such potato-based foods to restaurants, grocery stores, hotels, schools, sporting venues and so on. Its largest single customer is McDonald’s. You won’t be surprised to learn that Lamb-Weston is raising prices, but not quite enough to offset cost inflation—higher prices for shipping, packaging, edible oils, etc. It’s also—likewise unsurprising given nationwide trends—experiencing a staffing shortage. What’s more, the latest potato crop in the Pacific Northwest was “exceptionally poor” due to extreme heat. Demand, however, is “solid” as restaurant dining picks up. Lamb-Weston was once a subsidiary of food giant Conagra. It today employs nearly 8,000 workers, 27% of them unionized. But does it make money? In its latest fiscal year (that ended last May), the company earned a healthy 13% operating margin on $3.7b in revenue.

Tweet of the Week

Sectors

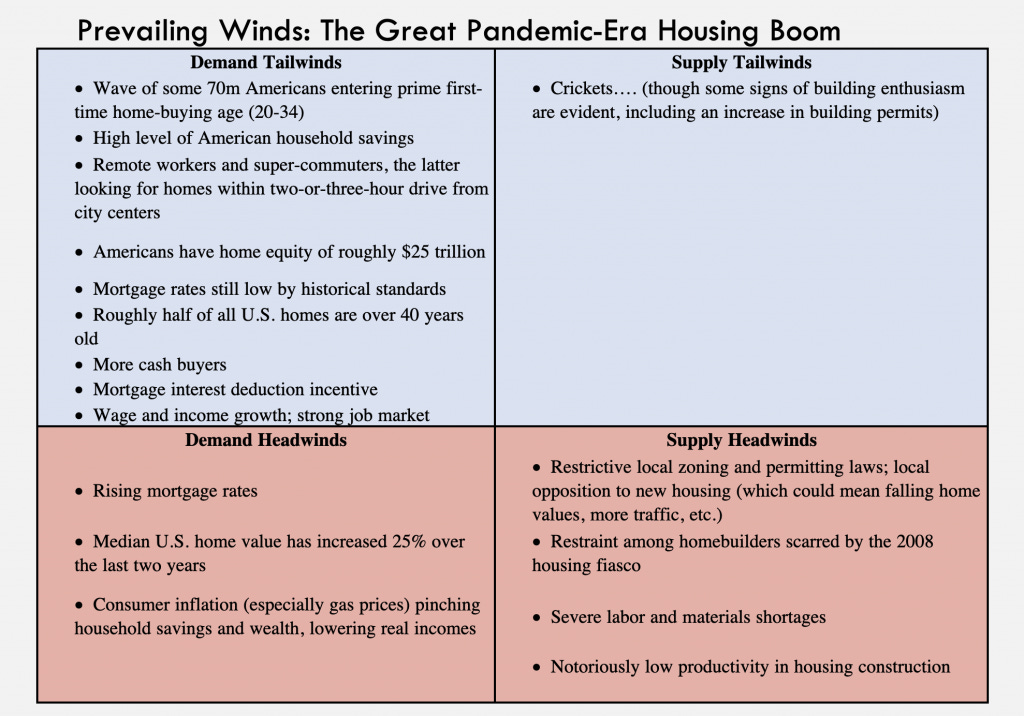

Housing: “Are we a society that actually wants home prices to go down?” Housingwire’s Logan Mohtashami asks this important question, which doesn’t have an easy answer. Homeowners love it when home prices rise, he said on the “New Bazaar” podcast. After all, roughly two-thirds of American families own their own home. The country’s 3m-plus real estate agents do well financially when home prices rise. So do many others in the vast housing sector ecosystem. Housing is a critical component of savings for retirement. In fact, whenever the economy starts to falter, the typical response is to lower interest rates to stimulate—most importantly—housing demand. People can also borrow against the rising value of their home, generating more spending power for the economy. You’ve surely heard the mantra: Buying a home is the best investment you’ll ever make.” Do we really want to cool down housing prices?

The problem, of course, is that rising home prices present a challenge for would-be buyers, including young families. In the extreme (like right now), it leads to homelessness. It makes inequality worse. It prevents people from moving into areas where good jobs are plentiful.

Of course, falling home prices have a huge cost for lower-income people too. Depressed property values mean low tax revenues, which means inferior public services, which in turn leads to further declines in property value—a toxic spiral. This can get really bad in areas with lots of local autonomy, where wealthier neighborhoods can essentially draw a line around themselves and avoid the obligation of providing services to nearby poorer areas.

The current ultra-spike in housing prices stems from a severe shortage, the result of under-building. At the same time, Mohtashami says, Americans are living in their houses longer, meaning less inventory for sale—inventories are currently at their lowest level ever relative to the population. The bottom line: “Whether you want home prices to rise or fall depends on who you are.”

Housing: During Jay Powell’s House testimony last week, one Congressman joked that a benefit of soaring home prices is that everyone’s now realizing their dream of living in an expensive neighborhood. Kidding aside, the housing shortage is a topic getting lots of attention these days, not least from academics studying its cause. One such person is Jenny Schuetz, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of the new book, “Fixer-Upper: How to Repair America’s Broken Housing Systems.” She notes that in some big metros like New York and Boston, homebuilders have been underproducing relative to demand for decades. One key reason why is that incumbent owners—people who already live there—are motivated to keep supply down to keep home values up. Some are concerned about more traffic or crowded schools. Some simply want to keep newcomers out. The result is building that can only occur far from city centers, leading to environmentally damaging commutes. About three-quarters of the land in many cities, Schuetz says, is zoned for detached single-family housing only. Many homes that exist today, in fact, would be illegal under today’s rules—multi-family row housing, for example. Housing policy, she adds, brings up all sorts of important questions. Should each neighborhood and community make their own zoning rules? Or should rules be made at a region-wide level to optimize for social and environmental outcomes? The labor market, importantly, is regional, not specific to individual neighborhoods. Should housing be part of the federal social safety net, and to what extent? Should homeowners have the right to build what they want on their own land?

Housing: We’ll mention one more point about construction from another good podcast discussion on housing. George Mason’s Alex Tabarrok noted on the Ezra Klein show that New York’s Empire State Building took just 410 days to build. Today, he said, you couldn’t even get a single permit in that time frame.

Markets

Commodities: With prices soaring, it’s a happy time for commodity producers. But that’s after a rough half-decade. Since 2010, in fact, the Goldman Sachs commodity index has been flat, notes investment manager Eric Mandelblatt, speaking on the podcast “Invest Like the Best.” In that same time, the Nasdaq 100 index has—remarkably—returned compounded annual growth of 20%. One reason for the decade-long poor performance of commodities? All the new supply introduced by China during the 2010s. The world is changing though, and today’s skyrocketing prices are not triggering a textbook supply response—for several reasons, according to Mandelblatt. One is the world’s concern about climate change, causing reluctance to invest in more fossil fuel energy. Some companies fear a future of high carbon taxes. Some were scarred by sharp commodity price declines in 2014 and 2020. Some are wary of heightened geopolitical volatility. In the meantime, demand for key commodities like copper is poised to steadily rise with growth in electric car output and other manifestations of the green transition—e-vehicles indeed require a lot more copper than ICE vehicles. But investment in new copper mines is scant—three of the world’s largest mines were developed more than a century ago. Alas, “We don’t think these supply challenges are going to be rectified in the near term,” Mandelblatt says. In other words, he sees high commodity prices persisting.

Regarding China, it for years used cheap and dirty coal to mass produce low-cost aluminum, steel and other commodities, Mandelblatt explained. It now generates roughly half the world’s aluminum. China also engaged in industrial production and construction on an immense scale—the scale of the industrial buildout in China over the last 20 years is “mind boggling.” He gives the example of steel—China consumes ten times as much as the U.S., even though U.S. GDP is larger. A key question for future commodity prices is to what extent China continues this pace of investment. Some economists expect a rebound post-Covid. Others see the popping of a Chinese property bubble currently unfolding, heralding much less construction going forward. Bloomberg’s Sofia Horta e Costa wrote last week that sales of China’s 100 largest property developers dropped a stunning 47% y/y in February.

Turning to Europe, it led the world in trying to wean itself off fossil fuels. But as Mandelblatt said, it’s now learning the hard way that doing so is much more challenging and more expensive than anticipated.

Government

Fiscal Policy: Some say Washington overstimulated the economy, helping to fan the flames of inflation. A new Moody’s Analytics study reaches a different conclusion. Absent the roughly $5 trillion in fiscal support, it argues, America’s real GDP would have contracted 11% in 2020, more than three times its actual decline. It then would have dipped again in 2021, recovering later in the year but never fully returning to its pre-pandemic growth trajectory. Instead, the economy is now on track to recoup all the jobs it lost during the pandemic this year—this would have taken until 2026 without the stimulus. True, high inflation wouldn’t be an issue today had the economy stayed depressed. But excessively low inflation would be, as it was in the decade following the 2008-09 recession. What’s more, the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio, which soared throughout the pandemic, would have jumped by a similar amount even without the fiscal boost, simply because the economy would’ve been so much worse and tax revenues so much less. The Moody’s research specifically underscores the importance of the $2 trillion American Rescue Plan (ARP) passed in March 2021. Did the economy really need this extra big dose of stimulus? Without it, “the U.S. economy would have come close to suffering a double-digit recession in spring 2021.” It adds: “The ARP is responsible for adding well over 4m more jobs in 2021, and the economy is currently on track to recovering all the jobs lost in the pandemic by the second quarter of this year… Although the ARP was costly to U.S. taxpayers, without it, the ultimate cost to them would have been equally as large.”

Returning to inflation, Moody’s says it only became a problem when the Delta wave of the pandemic hit last summer. Delta “slammed consumer demand” but also “severely disrupted supply.”

The Moody’s report also underscores the impact of fiscal programs in other large economies. Combined with the impact of vaccines and monetary stimulus, they helped the world as a whole recover the output and employment lost during the brief but severe recession in early 2020.

Places:

Tri-Cities, Washington: With apologies to Austin, Seattle might just be America’s strongest economy right now. You know the reasons why: Amazon, Microsoft, Boeing, Costco, Starbucks… But hours east of the Cascade Mountains, in Washington State’s south central region, there’s a lesser-known economic boom taking shape. And it looks nothing like Seattle’s boom. Kennewick, Richland and Pasco together constitute Washington’s Tri-Cities metro area, modest in size with roughly 300,000 people. That’s enough to make it the state’s third largest metro after Seattle and Spokane (counting Vancouver, Washington, as part of the Portland, Oregon metro). More interestingly, Tri -Cities is Washington State’s fastest-growing area, even exceeding Seattle’s electrifying growth. It was in fact the nation’s 30th fastest-growing metro nationwide during the 2010s, out of some 400 tracked by the U.S. Census. Population increased 17% over the decade, lured by sunny weather, outdoor activities, relatively affordable housing and nuclear waste. Wait, what? Nuclear waste? That story begins with the Great Depression of the 1930s, when New Deal engineering projects—the Hoover Dam is the most famous—created new population centers across previously uninhabited regions of the American west. As Pomona College historian Char Miller explains in a discussion with the publication Governing, Denver, Phoenix, Tucson, Albuquerque, El Paso, Las Vegas, Phoenix, San Diego and even mighty Los Angeles all owe their existence to large federal infrastructure projects. The same is true for Tri-Cities, which depends on water and cheap power from the New Deal-era Grand Coulee Dam to its north. Even today, such projects provide Washington State with some of the country’s cheapest electric power. During the 1940s though, cheap and abundant power was prized for another reason: The development of atomic weapons. Tri-Cities was selected as a major research site for the Manhattan Project, America’s secret project to develop a nuclear bomb. The Hanford nuclear plant, more specifically, produced the required plutonium, along with electricity, from 1943 until its closure in 1987. Together with its research arm, which became the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in the 1960s, the federal Hanford plant dominated the local Tri-Cities economy. By the mid-1980s, a quarter of its workforce, and a fifth its salaries and wages, were tied to federal dollars. When the plant closed in 1987, however, the federal money didn’t disappear. Instead, Hanford became a giant cleanup site, one of 15 such Department of Energy (DOE) projects nationwide. For years, solid and liquid waste was buried underground, contaminating ground water and soils. The DOE and six major contractors currently have some 10,000 people working on the cleanup, which is expected to continue into at least the 2060s. Soon, a new $17b plant will turn some of the liquid waste into glass through a process called vitrification. In the meantime, the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) has become a federally-funded economic force in its own right, with a $1b-plus annual budget for scientific research and development. Some of its work is for national security (i.e., ways to detect and prevent bioterrorism). Some is designed for commercial use, including work on clean energy and public health. The Hanford site and PNNL thus remain central to the Tri-Cities economy. But much less so than in the 1980s, when the plant’s closure was imminent. Today, the region’s dependence on federal dollars, in terms of jobs and wages, is roughly half what it was then, according to Karl Dye of Tridec, the area’s economic development council. That’s thanks to the rise of other sectors including agriculture (potatoes, apples, sweet corn, grapes, etc.), food processing, tourism, transportation, construction and of course education and health (you’ll find that everywhere). When the Hanford nuclear site closed, a modern nuclear plant opened nearby, which still provides power today. It’s in fact the only commercial nuclear plant in Washington state operating currently, and one of just 93 nationwide. The fact that Washington state doesn’t have a corporate or personal income tax surely helps draw companies and retirees to the Tri-Cities, fueling some of its rapid growth. Amazon will soon open two new 1m-square-foot warehouses in the area. The port of Pasco, along with the BNSF and Union Pacific railroads, help move agricultural and industrial goods to Pacific gateways and onto export markets like Asia. Tri-Cities is certainly feeling the national labor shortage, notably in its agricultural sector. It’s also experiencing the national run-up in housing prices, making it difficult to accommodate newcomers eager to fill open jobs. Another specific labor challenge is a wave of retirements among engineers, scientists and other professionals employed at Hanford and PNNL. They’re not easily replaced. (Sources: Tridec, Department of Housing/Urban Development, Department of Energy, U.S. Census, WPC Young Professionals).

The West: As referenced above, Governing.com’s interview with historian Char Miller sheds light on how many of the U.S. west’s largest cities owe their existence to grand-scale federal engineering projects, most importantly large dams that provide drinking water, water for farming and electricity. According to Miller, 40m Americans now obtain their water from the Colorado River thanks to engineering wonders like the Hoover Dam. But cities like Denver and Phoenix continue to grow and grow, to the point of stressing water supplies. Interestingly, he envisions a future wave of reverse migration, back to midwestern cities that were “emptied out” in recent decades, like Detroit, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh and Chicago. Why? Because the Great Lakes region is where 20% of the world’s freshwater supply is located.

Abroad

China: China expert Anne Stevenson-Yang has a good anecdote that captures China’s economic predicament. Interviewed on the “Eurodollar University” podcast, she recounted the experience of a remote and primitive town in western Sichuan she visited early on in China’s process of economic reopening. When a road was built to the provincial capital Chengdu, the local town’s economy perhaps doubled, propelled by a new ability to sell local goods to a large market of people. So the government built another road, which was helpful but less dramatically so. Then another road. And another, at which point it wasn’t adding much value if any. China’s economic rise has a lot to do with infrastructure investment—new housing, new factories, new ports for exporting, and so on. But there’s only so much investing a country can do before diminishing returns.

Looking Back

Immigration: The Economist featured an article on the history of modern globalization, which first took off in the mid-1800s. Improvements in communication (i.e., the telegraph) and transport (steamships and railways) meant faster, cheaper and more reliable movement of people, goods and information. This brought opportunity for the economies of Europe and the U.S.—the former had lots of workers but limited land while the latter had lots of land but too few workers. A natural consequence, especially in these times before border controls, was mass immigration. Between 1870 and 1910, the article notes, emigration reduced Sweden’s workforce by 20% (relative to what it otherwise would have been) while immigration increased America’s workforce 24%. This movement of labor led to a convergence of wages across the Atlantic, one that’s not dissimilar to the convergence experienced between American and Chinese workers in the past two decades. In today’s version of globalization, Chinese workers didn’t need to move to the U.S. Instead, they produced U.S.-bound exports at home. The Economist writes: “The narrowing gap between American and Chinese wages is in part a story of Chinese technological progress. Yet it is also one in which hundreds of millions of Chinese workers began participating in a global economy, making low-skilled labour more abundant globally and contributing to weaker blue-collar wage growth and higher inequality in rich countries.” As with 19th century globalization, however, 21st century globalization is causing a political backlash, clearly visible in support for trade tariffs during the Trump administration.

Immigration: Here’s another great immigration fact, this one from a PBS documentary “Destination America.” Between 1820 and 1975, it said, 4.7m people from Ireland settled in America. The population of Ireland today? About 5m.

Looking Ahead

Climate Change: Geopolitical events make it increasingly clear that the world can’t easily or inexpensively quit fossil fuels. But all the while, the threat of climate change worsens. Former Fed economist Galina Hale, now at the University of California, Santa Cruz, discussed the matter with “Econ Facts,” a podcast. The U.S. is already experiencing extreme weather linked to climate change, including storms, droughts and wildfires. As global temperatures rise, moreover, rising sea levels are already starting to flood major cities like Miami and New York during storms. Financial institutions, she says, need to recognize and disclose their exposure to climate change risks, including those pertaining to real estate holdings in areas subject to flooding and wildfires. She warns too that the cost of transitioning away from carbon-intensive energy, while expensive, will get even more so the longer the world waits. That’s because natural disasters will become more frequent, more severe and indeed more costly if global temperatures aren’t stabilized soon.

Climate Change: The U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a new report on the threat. It said “increased heatwaves, droughts and floods are already exceeding plants’ and animals’ tolerance thresholds, driving mass mortalities in species such as trees and corals.” Warming temperatures are also exposing millions of people to “acute food and water insecurity, especially in Africa, Asia, Central and South America, on Small Islands and in the Arctic.” As Hale pointed out, wealthier people and places tend to have larger carbon footprints but less immediate exposure to the risk, making the challenge of decarbonizing the economy more difficult politically. Addressing the problem more broadly, the IPCC report warns: “People’s health, lives and livelihoods, as well as property and critical infrastructure, including energy and transportation systems, are being increasingly adversely affected by hazards from heatwaves, storms, drought and flooding as well as slow-onset changes, including sea level rise.”

Genetic Sequencing: A letter published by The Economist from a Mr. John Walls of Glasgow raises an important point about the insurance implications of diagnosing rare diseases from genome sequencing. While this could yield important medical benefits, Walls points out: “Such records identify a baby’s predisposition to illness and would be a gold mine to insurance companies seeking to avoid future risk. When the babies become adults, they may find they can’t get insured or must pay excessively high premiums on a range of policies from mortgages to travel.” You can see the ethical, moral and economic questions this could trigger.