Place of the Week: Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Tough Breaks on the Great Lakes

Econ Weekly (Dec. 13, 2021): The Most Important News, Ideas and Trends from Across the U.S. Economy

THIS WEEK’S FULL ISSUE FREE TO READ:

Issue 48: December 13, 2021

Inside this Issue:

Again, Prices Spike: When Will Powell Hike?

This Week, A Taper Tweak? FOMC Set for Last Meeting of 2021

Debt Ceiling Healing: Congress Dodges Default

Prosperous Parts Peddler: AutoZone a Metaphor for Retail Nirvana

Housing Still Hot: Demand Still Stellar Says One Home Seller

Portage Amid Shortage: Trucking Firms Aspire to Hire

Alternative Medicine: Investing Beyond Stocks and Bonds

When Dino-Sears Roamed: The Saga of a Mighty, Mighty Merchandiser

Lehman’s Demons: On the Front Lines of the 2008 Financial Collapse

And This Week’s Featured Place: Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Tough Breaks on the Great Lakes

(reminder: Econ Weekly publishes 48 issues a year. We will return Jan. 3rd, 2022)

Quote of the Week

“My hope is late spring, early summer we get back to some semblance of normality. But every time we thought, OK this one is easing, there has been another part of the supply chain that has shown challenges.”

-AutoZone CEO Bill Rhodes

Market QuickLook

The Latest

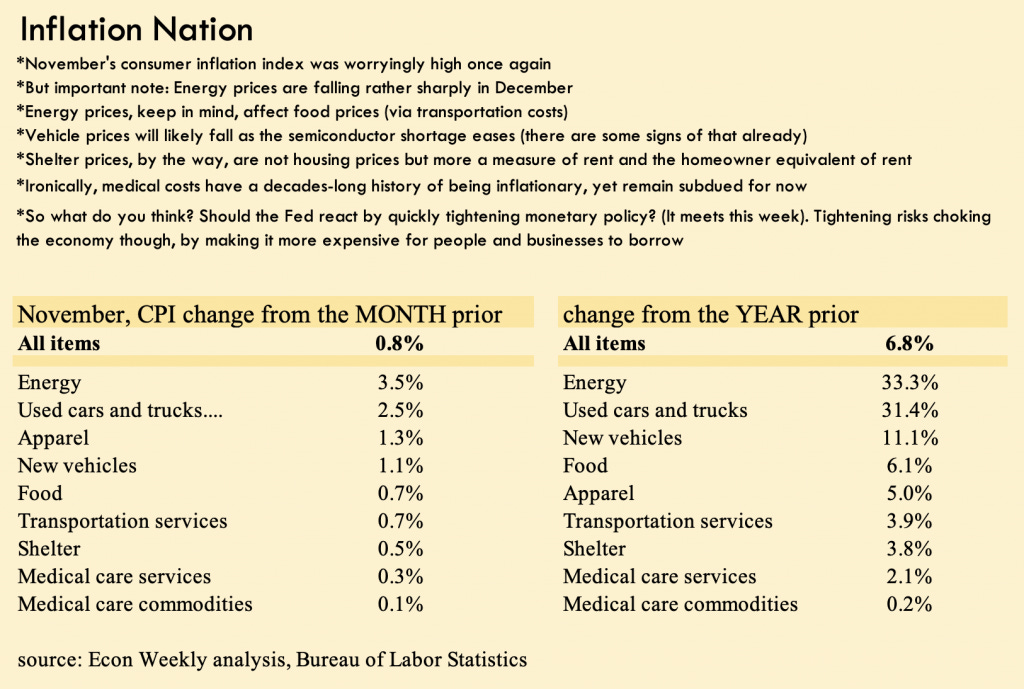

Yikes, 6.8%. That’s November’s dizzying y/y increase in consumer prices, reinforcing concerns that inflation is a major threat to the U.S. economy—a threat the Federal Reserve needs to confront, pronto. From just October to November, the Labor Department’s CPI index jumped 0.8%, following its 0.9% leap from September to October. Yes, the Fed has a new policy of greater tolerance for inflation that runs above its 2% target for a while. But 4.8 points above?

The Fed’s policy committee (the FOMC) holds its eighth and final meeting of 2021 this week, where it might decide to accelerate the windup of its stimulative bond-buying program—Chairman Jay Powell recently told Congress he would consider doing so. Some economists also want a quick succession of interest rate hikes in 2022, to ensure that inflation doesn’t spiral out of control. It’s already starting to feel that way, with big price spikes in everyday purchases from gas to groceries.

It’s more than just a bad feeling. Americans last month saw their hourly earnings decline nearly 2% y/y, adjusted for inflation. Yes, wages are rising across the country. But prices are rising faster. One important caveat is that lower-income workers, in industries like hospitality, are in fact seeing wage gains outpace inflation. That’s a welcome development for an economy struggling with widening inequality. Also keep in mind that inflation isn’t a bad thing for everyone—if you’re a debtor, like someone with a home mortgage—or the U.S. government, for that matter—it’s helpful to make repayments in less valuable dollars.

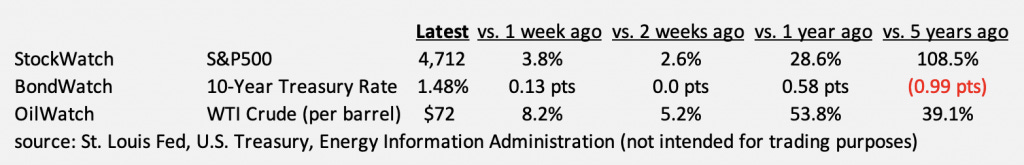

That said, most will agree that 6.8% inflation isn’t healthy for the economy overall. It reduces purchasing power for most households. It makes it difficult for businesses to plan. It crushes people with fixed incomes. It’s bad for lenders, including banks and bond investors. And that in turn implies scarcer and more expensive credit for prospective borrowers. Credit for now remains abundant and cheap, in part because of the Fed’s loose-money policies. But that looseness will soon tighten. For now, the appetite for lending money to the U.S. government for long durations remains robust. Notwithstanding a modest increase last week, yields on 10-year government Treasury bonds stand at just 1.48%. Keep in mind, though: The Fed currently owns more than a fifth of all outstanding Treasury debt.

Alright, so inflation has become a big problem. Everybody agrees, right? Wrong. Many prominent economists still argue that the longterm trajectory of prices is down, not up. For most of the pandemic, the U.S. has lived in a sort of Bizarro inflation world, in which normally inflationary sectors like health care, housing and higher education (the Three H’s) have stopped seeing major price increases. But durable goods like autos and household appliances, deflationary for decades, have suddenly seen prices soar. Consider these annual rates of inflation for November: health care just 2.1%, college tuition 1.9% and housing rent 3.0%.

But already, there are signs of a return to normal patterns. Rents and their ownership equivalent are picking up. Same for categories like doctor visits. Few expect costs for health insurance and college to remain subdued for long. In the meantime, the ferocious pandemic-era rise in auto prices directly stems from a semiconductor shortage that now shows early signs of easing. Widespread shortages of other products and inputs should similarly ease as supply chains adjust and Covid stops messing with the labor market. Demand, too, should eventually cool as households draw down their stimulus-juiced savings. Importantly, energy prices sharply dropped after the November CPI figures, before rebounding somewhat last week. Other commodities have been dropping in price as well, which if sustained, would exert downward pressure on food prices. Be mindful of how everything is connected: If fuel prices drop, so will the cost of road, rail, sea and air transportation, a major input cost for most of what Americans buy. Walmart once said the best predictor of its sales was the price of gas—when it was high, people bought less at its stores, and vice versa.

Ultimately, the persistence of disturbing inflation will depend on a multitude of factors, including commodity prices, labor participation, consumer behavior and government policies, most importantly the extent to which the Fed uses monetary tightening as a tool to squeeze demand. The lingering Covid scourge continues to influence all of these areas, producing many unknowns about what the economy will look like once the pandemic is finally over. Have labor markets changed permanently, for example? Or will they snap back to pre-pandemic norms?

Another looming uncertainty is the fate of the flourishing stock market, which jumped to new highs last week after several weeks of retrenchment (reassuring news about the debt ceiling and the Omicron variant helped). Anecdotally, there’s escalating chatter about an overdue correction in prices. Bloomberg News reports that many company founders and leaders are unloading their stock to cash in at a high level. But who knows? Maybe traditional measures of equity value are poor gauges of the true worth of Silicon Valley’s superstars. They and so many other companies across the economy, after all, are earning record profits as demand strength supersedes cost inflation. And it makes sense that the stock market would perform well in an economy where almost everyone who wants a job can have one—unemployment claims haven’t been this low in decades.

Investment is booming too, perhaps most consequentially in the auto sector. According to The Wall Street Journal, GM will spend $3b to build electric vehicles in Michigan. And according to Bloomberg, the Amazon-backed EV maker Rivian seems poised to build a factory in Georgia. America’s industrial age may have passed, giving way to an economy more linked to services like health care, education and finance. But autos remain central to the fortunes of large swaths of the U.S., most importantly areas between the Mississippi River and the Eastern Seaboard, i.e., the Midwest and Old South.

In the new and emerging market for digital assets, made possible by cryptography and blockchain technology, all of global finance stands to be disrupted. In the first Congressional hearing dedicated to the cryptoeconomy, business leaders discussed—among other things—the future of stablecoins. They’re today used mostly to facilitate trading of other digital assets (i.e., cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin). But as President Biden’s Working Group on the topic noted, they could one day become a dominant form of payment by households and businesses. One executive testifying sees dollar stablecoins soon flowing across the internet like emails and text messages. Should their issuers be required to hold a banking license, as the Working Group believes? Or would that stifle innovation and encourage an online economy of stablecoins in rival currencies?

Beyond just stablecoins serving as a payment tool, the cryptoeconomy more broadly—to its champions, anyway—promises a new version of the internet. A version that’s decentralized and poised to produce new products, services and applications, along with new means of exchanging value and coordinating economic activity. No wonder why Congress wants to be involved.

Elon Musk doesn’t like President Biden getting involved in the auto market, complaining of favoritism toward unionized carmakers. He’s criticizing Biden’s Build Back Better plan too, expressing concern about rising federal debt. Tesla, SpaceX and Solar City, it should be said, owe much of their existence to federal dollars. As for exactly how the BBB plan would affect federal finances, that’s currently the hot debate on Capitol Hill. Its fate will depend heavily on what Joe thinks. No, not Joe Biden. Joe Manchin.

Joe DiMaggio is surely looking down with disappointment as a labor dispute rocks Major League Baseball. Starbucks has labor troubles as one of its stores in Buffalo voted to unionize. Costco, another Seattle company with a labor-friendly reputation, delivered another quarter of prolific profits, never mind that nearly 80% of its import containers are arriving an average of 51 days late. Some toys, it said, won’t make it before Christmas. As for Seattle’s other giants, Microsoft appears set to secure E.U. approval for its takeover of Nuance Communications. Amazon suffered a major IT outage last week, affecting its AWS cloud computing service, today a bedrock of Corporate America’s digital infrastructure. Amazon, separately, according to CNBC, is now shipping 72% of its own packages, up from 47% in 2019.

Seattle’s Boeing, alas, (never mind its official Chicago headquarters) is a rare U.S. corporation having a dismal 2021, beset by the downturn in global aviation and self-inflicted production woes. Boeing did get some welcome news from China, which reauthorized use of its B737-MAX jets. But heavy dependence on China is becoming uncomfortable at a time when the U.S. increasingly views China as an enemy power. It’s not just Boeing, of course—the entire U.S. economy depends heavily on trade with China. Helpfully, China’s economy is even more reliant on trade with the U.S., a co-dependence that perhaps mitigates the risk of a rupture. But it’s a topic companies will watch with some nervousness in 2022.

Heading into 2022, the three central themes of the U.S. economy remain: Demand strong, supplies constrained, prices up. This is Econ Weekly’s final issue of 2021. We’ll be back after the winter break, starting with our January 3rd issue. Until then, happy holidays! -Jay Shabat, Publisher

Companies

AutoZone, a Memphis-based auto parts retailer, never had it better. Sales are at all-time highs, reflective of an economy with exceptionally strong demand. Business has grown by roughly a quarter since the start of the pandemic, and every time executives think a cooling off is imminent, it never happens—demand continues to remain exceptionally strong today. An increase in discretionary income, aided by government stimulus and the strong job market, help explain why demand is so strong—most U.S. companies will attest to this. More unique to AutoZone is the boost from more people returning to the roads, resulting in higher maintenance needs and part failures. In addition, with new and used car prices way up, more Americans are holding on to the cars they have, even if that means spending more money to maintain and repair them. What’s more, the heightened frequency of extreme weather implies more part failures. More generally, the segment of customers AutoZone calls “financially fragile” began the pandemic with more time to spend working on their cars (because many were furloughed) and more money to spend on their cars (because of stimulus checks). It thought sales would tail off as the job market improved and stimulus waned. But again, demand has held strong, which puzzles executives. Along with selling parts to consumers in its network of 6,000 U.S. stores, AutoZone distributes parts to repair garages, car dealers, service stations and local governments. It employs 100,000 workers, nearly 90% of them in the U.S. And one of its key strategic moves is building larger stores with more inventory. But can it secure more inventory? That certainly is a challenge right now. Its supply chain, it says, wasn’t built for a 25% surge in demand that’s lasted for more than 20 months. “Our in-stock levels are not where we want them to be.” One specific area of shortage right now are brake rotors. Early on, the problem was securing enough container space from Chinese ports like Shanghai. Now its products are getting shipped but unable to get through clogged U.S. ports. The Chinese New Year, when many factories shut down, could bring new difficulties in early 2022. Naturally, all of this supply chain messiness is driving up costs. But AutoZone says it has enough pricing power to respond effectively.

Toll Brothers, a homebuilder based near Philadelphia, provided a window on the current state of the housing market. It remains “very strong” across all geographies, the company said. And it still looks good moving into 2022. “The housing market has been driven by solid fundamentals, including favorable demographics, pent-up demand from over a decade of underproduction of new homes, low mortgage rates and a tight resale market.” The underproduction is nothing less than a national crisis, causing home prices to soar (especially in places with the most jobs) and homelessness to rise. But for homebuilders that managed to survive the recession of 2008-09, times are good. And for homeowners and home sellers, times are also good. The mortgage market, meanwhile, is free of the dodgy loans that plagued the early 2000s. Toll Brothers highlighted the ongoing migration to Sunbelt and Mountain states as Americans go “chasing the sunshine, chasing the jobs, chasing the lifestyle [and] chasing affordability.” In states like Idaho, Florida, Texas, North Carolina, Nevada, Arizona and Colorado, as much as 40% of demand is from buyers coming in from a different state. Executives downplayed the risk of higher interest rates, which would make mortgages more expensive. But it did say supply chain disruptions and labor constraints remain a big problem. The shortage of labor, in particular, is affecting not just construction but also things like land sales and municipal government inspections. Helpfully, lumber and other commodity prices are down from their highs. But costs are volatile.

SentinelOne: One hot area of Silicon Valley is cybersecurity, as the latest results from SentinelOne make clear. It’s still a young, relatively small, money-losing company, founded in 2013. Its Q3 revenues were just $56m. But that represented $128% y/y growth, the result of an “incredibly strong” demand environment. Q4, which tends to be when many companies make IT purchasing decisions, expects to be similarly strong. The company, with roots in Israel, uses artificial intelligence and other technologies to protect mission critical and other systems from cyberattacks, a growing threat as more devices join the internet. In addition, the rise in hybrid work and bring-your-own device policies create new targets for attackers. The market is competitive though, with Crowdstrike among SentinelOne’s chief rivals. When asked recently to cite his biggest worry about the economy, Fed chair Jay Powell cited a cyberattack on the nation’s financial system. Geopolitics and war, furthermore, are increasingly conducted in cyberspace. One recent book on cyberweapons is entitled: “This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends.”

Tweet of the Week

Sectors

Trucking: Some companies are dealing with labor shortages better than others. Few are facing more difficulties than U.S. trucking firms. While demand for shipping stuff is red hot, drivers are in short supply, especially for long-distance overnight trips. One firm, Connecticut-based XPO, says it’s graduating roughly double the number of drivers from its schools as it did in 2019. “And we are looking to further double that number going into 2022.” It’s also doubling the production of trailers next year, while adding and expanding freight terminals. Another trucking company, Kansas City-based Yellow, said last month it’s held 127 hiring events and 14 job fairs across the country this year. But forecasters say shortages will persist, in line with a long running trend. XPO separately called attention to the threat of vaccine mandates, noting: “In the trucking industry, in particular, there’s probably a little bit higher percentage of people who are anti-vaxxers, so to speak. And if that policy [a mandate] went in right away, it probably would not, short-term at least, have a good effect. You’d see a lot of labor leave the market.” As an interesting side note to the nation’s driver shortage, Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast last week featured a look at how it’s affecting school bus companies and the communities that depend on them.

Air Transport: What’s been the busiest U.S. airline route in 2021? Measured by number of flights, it’s Los Angeles-San Francisco—that according to a new Airline Insights Review just published by the aviation data firm Cirium. Los Angeles-Las Vegas ranked second. As usual, Atlanta was the busiest airport, not just in the U.S. but worldwide. Chicago, Dallas-Fort Worth, Denver, Charlotte and Los Angeles were next in the rankings.

Markets

Alternative Assets are typically defined as those other than stocks and bonds, including real estate, infrastructure, private debt, natural resources and private equity (some might add digital assets in the crypto-sphere too). Their appeal? They offer the possibility of higher returns, which becomes more important when interest rates are low as they currently are. As a result, fundraising for alternative assets this year has surpassed $1.1 trillion, according to Moody’s, as reported by Institutional Investor. Total alternative assets under management now exceed $9 trillion. Aside from being a prompt to seek alternative ways to earn yield, ultra-low interest rates also encourage more investing with borrowed money. That has Moody’s concerned about systemic trouble tied to rising credit risk. Neal Epstein of Moody’s tells Institutional Investor: “Private equity funds typically conduct leveraged buyouts, and, as the asset class grows, so does the amount of borrowing.” Trouble could come if rates increase, or if the economy sours. “Because rates are lower,” Epstein said, “weaker creditors have been tempted to buy more. But if rates rise, they may not be able to support the debt.” Another issue is that alternative asset investments are often made for long durations, implying illiquidity in the short-term. You can’t quickly exit like you can with stocks and bonds.

Tech Stocks: Bilal Hafeez, on his Macro Hive podcast, underscores the difficulties in properly valuing tech companies. Facebook/Meta stock, for example, looks expensive based on the value of the assets on its balance sheet. The problem is that its balance sheet fails to capture what’s perhaps its most valuable asset: its network of 2b people. When it spends on marketing, he adds, that’s treated as an operating cost for accounting purposes. But it’s really more like a capital expenditure, because it helps build the network.

Government

Health Care: The federal government plays a major role in the giant health care sector, and not just through the Medicare and Medicaid programs (for seniors and lower-income people, respectively). It also runs the Military Health System (MHS), administered by the Department of Defense. The OD runs its own hospitals and clinics for servicemembers, military retirees and their family members, who can also see civilian care providers who accept Tricare insurance coverage. According to the Congressional Research Service, MHS offers health care benefits and services through its Tricare program to approximately 9.6m Americans. Does it cover 100% of all costs? Only if you’re an active-duty service member. Others share part of the costs by paying premiums (i.e., enrollment fees), deductibles, co-payments and coinsurance. All told, the Defense Department spends about $50b a year on health care, or about 7% of its total budget.

Defense: There’s a new defense budget proposal passed last week by the House of Representatives. It features $768b in spending and mentions China 164 times. Russia is mentioned 94 times. One provision requires the Secretary of Defense to report on the cost of redirecting personnel and materials to “effectively engage in great power competition with Russia and China.” The proposal, which like President Biden’s Build Back Better bill still needs Senate approval, also includes more money for ships, planes and allies. The Economist, citing Seamus Daniels of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, says personnel costs account for nearly a third of the Pentagon’s budget, “a figure that keeps rising despite America fielding the fewest troops in decades.” For many communities across the U.S., Pentagon spending dominates the economy and local labor markets.

Places:

Upper Peninsula, Michigan: There are no shuttered auto factories in this part of Michigan. Just shuttered mines, shuttered timber companies and a shuttered Air Force Base. Shattered, meanwhile, are dreams and goals of growing the local economy, something hard to do with a shrinking population. The large area of northern Michigan called the Upper Peninsula, territorially disconnected from the rest of the state, has all too many of the unfortunate hallmarks of struggling rural America. A declining and aging population stands among them, with too few jobs to retain natives, let alone attract newcomers. The U.P., surrounded by the Great Lakes, is home to about 300,000 people today, a 3% decline from ten years ago. In Luce County, one of 15 counties on the island, population plummeted by 20%. In some areas, some 40% of all residents are over 65, compared to 17% nationally. The U.P.’s struggles aren’t new. The height of its prosperity was roughly 100 years ago, when its iron ore and copper helped fuel America’s early industrialization. But much of the mineral wealth was eventually depleted—the last copper mine closed in 1995. Just one major iron ore mine remains, owned by Cliffs Natural resources and located not far from Marquette—that’s the U.P.’s largest town with about 20,000 people. Not far is the country’s only high-grade nickel mine, though deposits will run out by 2025. During its heyday, immigrants poured in to work the mines, from England, Ireland, Germany, Canada and—most unusually—Finland (roughly 35% of today’s U.P. residents claim Finnish heritage). As mines disappeared, the K.I. Sawyer Air Force Base helped cushion the blow. But that closed in 1995. What’s left is an economy highly dependent on the bedrock sectors of health care, local government and education. That includes Marquette General Hospital and Northern Michigan University. Cliffs, according to the Lake Superior Community Partnership, is the U.P.’s largest non-health care private employer (about a thousand jobs). Walmart ranks next. American Airlines operates a small maintenance base at Marquette’s airport, where travelers can find nonstop flights to Chicago, Minneapolis and Detroit. Airports in Hancock, Sault Ste. Marie and a few other U.P. towns offer commercial air service, but only on small jets. Flights cater mostly to tourists, another critical component of the peninsula’s economy. Visitors come mostly from mainland Michigan and neighboring states like Wisconsin. Some come for Canada, though the border was closed during much of the Covid crisis. Most come during summers, though winter sports are an attraction as well. So are casinos operated by Native American tribes. The U.P. is not an easy place for tourists to reach, however, with its limited air service and just one bridge link to the rest of Michigan. In a word, it’s remote. For those living in the peninsula’s west, Green Bay, Wisconsin, is the nearest population center. Like many rural communities across the U.S., attracting skilled workers was a challenge well before the pandemic. Now it’s even tougher. Insufficient housing, a lack of childcare options, a dearth of broadband connections, limited ethnic and racial diversity and strained public budgets are all obstacles to recruiting teachers, engineers, public administrators, health care professionals and so on. Only 2% of the local population is foreign born. Agriculture isn’t big simply because of the harsh weather. Real estate, on the other hand, is one area with some vibrancy, boosted by the market for short-term rentals to visitors. That can be controversial, given its impact on local housing costs. No less controversial are plans for a Canadian energy pipeline running through the U.P. The recently passed infrastructure bill, on top of three Covid relief bills, have provided rural communities like the U.P. with a large quantity of available funds for development. Securing these new funds, sometimes through a grant process, presents a unique opportunity. But using the new money wisely is critical. One not-so-fun fact about Michigan: It was the only state in the U.S. to lose population between 2000 and 2010, before growing slightly (2%) during the 2010s. Detroit and its auto sector, of course, heavily influence Michigan’s demographic destiny. But declines in the Upper Peninsula aren’t helping. (Sources: U.S. Census, Finland Abroad, Lake Superior Community Partnership, Rural Insights, Minneapolis Star-Tribune)

If Michigan was the only state whose population declined in the 2000s, what were the states whose population declined in the 2010s? There were three: Illinois, Mississippi and West Virginia. Puerto Rico, a territory, shrank too—by a lot (12%). The fastest growing states were Utah and Idaho.

New York City: What was the largest “industrial cluster” in the 1950s? The concentration of auto manufacturing in Detroit would be a good guess. But Harvard professor Edward Glaeser says no, it was garment manufacturing in New York City. Glaeser, an expert in urban development, shared his thoughts on the Macro Hive podcast. New York’s garment sector would get clobbered by globalization, with much of that work going overseas where labor costs were cheaper. That contributed to New York City’s severe economic decline, culminating in its near bankruptcy in 1975. Marc Levinson’s book “The Box,” incidentally, reveals how container shipping decimated New York City’s port economy. In any case, the city experienced a stunning revival in the decades that followed, propelled in large part by a boom in finance. Glaeser recounts how post-war economists like Fischer Black and Myron Scholes introduced revolutionary new financial ideas and equations, taking much of the mystery out of concepts like managing risk. This new quantitative approach led to new financial products, from leveraged debt to mortgaged backed securities. Combined with advances in computing and information technology, it offered lucrative new ways for New York’s financial sector to earn money. At one point, Glaeser says, finance and insurance were responsible for more than 40% of Manhattan’s jobs. New York renaissance really took root in the 1990s, following the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s. Information industries like finance, higher education and health care were certainly critical. But so was the role New York began to play as a place for fun and entertainment, for people all across the world. In the meantime, many of New York’s laid off garment workers went on to start other companies in other sectors, aided by the entrepreneurial skills the garment trade often required. This was different, Glaeser says, than in Detroit, where the labor market was filled with a large pool of workers great at making cars but lacking entrepreneurial experience. He separately mentions Seattle and its large contingent of aerospace engineers employed by Boeing. Many were naturally college graduates, and so were their children, creating a highly educated labor pool well positioned to take advantage of the boom in knowledge sector industries that continues today.

Glaeser makes one other thought-provoking point: In America today, he says, the barriers to entrepreneurship are negligible for say, a college kid starting a software firm from his or her college dorm. But they’re much steeper for say, a poor person planning to open a neighborhood grocery store, which would require a litany of permits and licenses. It’s another example of the inequality that many economists blame for holding back GDP growth.

Looking back

Sears: The retail sector is littered with the carcasses of once-great companies, perhaps none more prominent than Sears. It’s not quite dead just yet, with a handful of stores still open But it’s a tiny shadow of the dominant company it once was. “The Big Store,” a book written by Don Katz in 1986, chronicles the rise of Sears and the severe problems it encountered in the late 1970s and early-to-mid 1980s. The company was founded in Chicago during the 1880s, by a watch salesman named Richard Sears, teamed with Alvah Roebuck. During its first few decades—a time when half of all Americans lived in rural areas—Sears thrived with a mail order business. Not unlike Amazon today, with its fulfillment centers along highways, Sears had regional fulfillment centers along rail lines, delivering goods that people ordered from its catalog. By the roaring 1920s, the golden age of the Sears catalog had already passed, and the company’s main growth engine was its network of stores. By 1932, according to Katz, its volume of sales from stores had surpassed that from its catalog. Naturally, it had to navigate challenges like the two world wars and the Great Depression. But after the second world war, it shrewdly followed its urban customer base to the suburbs. That allowed for extremely rapid growth, which led to dominance of America’s retail sector throughout the 1950s and 1960s. It employed what were widely regarded as the best business managers in the world. It was a critical customer for manufacturers throughout the economy. It even ran a large insurance company called Allstate (which became independent in the 1990s). The trouble began in the 1970s. New discount competitors began to surface, most importantly K-Mart. The Sears management structure, divided into five highly independent territories, proved problematic when cost control was a priority. The inflation-scarred 1970s proved challenging for all retailers, especially those like Sears whose success depended on extending credit to customers (inflation is a curse for creditors). By the late ’70s, it was no longer financing itself through customer sales but instead needed to rely itself on credit, often in the form of high-interest longterm debt. The sharp recession of the early 1980s, induced by sharp Federal Reserve monetary tightening, was especially painful. Much of Katz’s book focusses on the tenure of Edward Telling, the company’s chairman from 1977 to 1984. Perched in Chicago’s skyscraping Sears Tower, he led what momentarily proved a major turnaround, aided by the economic recovery of the 1980s. Telling shook up company culture by confronting divisional fiefdoms and clawing back control of key merchandising decisions. A major priority was diversifying away from overreliance on merchandise retailing, which led to the purchase of a real estate firm (Coldwell Banker) and an investment bank (Dean Witter). At one point, it even looked at buying John Deere, the tractor maker, and Disney. Sears wanted to sell everything from socks to stocks. In 1984, Sears was still the seventh largest U.S. company by sales. But now it was a web of different businesses, with thoughts of even going into health care. Sears was the largest customer, by the way, for both IBM and AT&T, both giants of the 1980s-era U.S. economy. Somewhat prophetically in 1988, it teamed with IBM, as well as the media network CBS, to launch an internet-like service called Prodigy, envisioning a world in which people shopped for items at home via their computers. Alas, it would be others that seized on its vision. In the 1990s, Sears—and K-Mart for that matter—missed the Big Box trend, in which suburban consumers moved from indoor shopping malls to free-standing mega-stores situated along major highways. Sears lost its title of America’s largest retailer in 1990—to the Big Box champion Walmart. In 1993, Sears discontinued its catalog, not to mention its network of fulfillment centers which would have come in handy for the e-commerce age. Its mall real estate, once a prized asset, lost value as people stopped going to malls. Stores were now staffed with many part-time teenage workers, alongside veterans nostalgic for the good old days. That created cultural problems. Losses mounted. The 2008 housing bust was painful. A hedge fund stepped in. Stores closed. K-Mart bought Sears in 2004. The combined company filed for bankruptcy in 2018. And today, just a few stores survive as part of an entity called Transformco, owned by the hedge fund ESL Investments. Sears, incidentally, closed its last store in its home state of Illinois just a few weeks ago.

Sears: Last week, the Cincinnati radio station WVXU did a story about build-it-yourself homes from the early 1900s. In 1908, Sears began selling house blueprints, followed soon after by the required building materials like lumber. According to Cindy Catanzaro of Springfield, Ohio, who lived in a Sears kit home, the company sold more than 70,000 home kits between 1908 and 1942. Talk about the “Everything Store”… not even Amazon sells houses!

The Fed and the Financial Crisis, Sept. 16, 2008: The first decade of the new millennia started out rough. Recession. A major terrorist attack. Wars in the Middle East. But by 2005, the U.S. economy was humming again, propelled by a monstrous boom in housing markets. Even at the time, it felt a bit too frothy, prompting debate and discussion within the Fed. It would in fact raise interest rates to try and quell the boom, softly. In 2006, housing markets indeed softened, signaling progress. But things began turning scary in 2007. That August, Fed officials warned: “Financial markets have been volatile in recent weeks, credit conditions have become tighter for some households and businesses, and the housing correction is ongoing.” Still, it expected the economy “to continue to expand at a moderate pace over coming quarters, supported by solid growth in employment and incomes and a robust global economy.” Later that month, its message was somewhat more pessimistic, noting “increased uncertainty” that might “restrain economic growth going forward.” In September, it lowered interest rates, responding to “downside risks to growth [that] have increased appreciably.” In December 2007: “incoming information suggests that economic growth is slowing, reflecting the intensification of the housing correction and some softening in business and consumer spending. Moreover, strains in financial markets have

increased in recent weeks.” All the while, it worried that “elevated energy and commodity prices, among other factors, may put upward pressure on inflation.” As the calendar turned to 2008, that pressure intensified. Here’s what the Fed said in January: Financial markets remain under considerable stress, and credit has tightened further for some businesses and households. Moreover, recent information indicates a deepening of the housing contraction as well as some softening in labor markets.” Then March: “The tightening of credit conditions and the deepening of the housing contraction are likely to weigh on economic growth over the next few quarters.” That summer, oil prices reached well above $100 a barrel. But the Fed, now pumping money into the financial sector, at least had hope that “over time, the substantial easing of monetary policy, combined with ongoing measures to foster market liquidity, should help to promote moderate economic growth.” And then came the fateful month of September. On the 15th of that month, the investment bank Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy. And unlike the prior failures of Bear Stearns and the housing agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, there was no Federal bailout this time. Markets went into freefall. On Sept. 16th, the Fed’s policy committee gathered to assess the crisis. That same day, incidentally, the Board—using emergency authority granted by Congress under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act—gave AIG an $85b loan, in exchange for an 80% ownership stake. AIG was the world’s largest insurance company, with more than 30m commercial, institutional and individual customers. What got it into trouble was selling insurance policies (credit default swaps) on housing-related debt securities that were suddenly defaulting in droves (the Fed would eventually recoup all of its AIG money and then some). Chairman Ben Bernanke and his team were in the meantime scrambling to provide other areas of the global economy with badly needed dollar liquidity. That includes international banks, for which the Fed devised a new policy: Currency swap lines with foreign central banks. A surge in demand for Treasury bonds further underscored the mass flight to safe assets. Money market funds, normally considered safe, were facing big demands for withdrawals. In the real economy, “conditions remained dismal.” The San Fran Fed mentioned providers of real estate services such as title insurance having cumulative employment reductions in the range of 40% to 50%. It also reported high levels of home foreclosures in Arizona, California and Nevada. Atlanta Fed chief Dennis Lockhart foresaw a protracted credit crunch that “would likely operate as a substantial drag on the economy.” Boston’s Eric Rosengren said “individuals and firms will become risk averse, with reluctance to consume or to invest… Deleveraging is likely to occur with a vengeance as firms seek to survive this period of significant upheaval.” San Francisco’s Janet Yellen provided some levity with news of “East Bay plastic surgeons and dentists [whose] patients are deferring elective procedures.” She added: “The Silicon Valley Country Club, with a $250,000 entrance fee and a seven-to-eight-year waiting list, has seen the number of would-be new members shrink to a mere thirteen.” There was simply no way of knowing exactly how bad things would get. Charles Evans of Chicago: “In one or two weeks, we may know better that either the economy will somehow muddle through, or we’re likely to be facing the mother of all credit crunches.” As it turned out, the Great Recession was determined to have started in December 2007. And it didn’t end until June 2009.

Looking ahead

SpaceX began building the launch pad for its Starship rocket, designed as a reusable freighter to deliver cargo into low earth orbit. The launch facility will be located at the Kennedy Space Center on Florida’s Atlantic Coast. A separate Starship facility is nearing completion on the Texas border with Mexico. Much of SpaceX’s business currently comes from NASA and the U.S. military. Many, however, envision a more vibrant private sector space economy in the future.

PLEASE VISIT www.econweekly.biz. Individual subscriptions available for just $15 per month. Company and University licenses also available.

Interested in contributing or partnering with Econ Weekly? I’d love to hear from you. Email me at jay@econweekly.biz. And be sure to sign up for my free newsletter about the North American railroad industry: