Inflation Demons, Haunted Housing and More Frustrations for the Auto Industry...

PLUS: This Week's Featured Place: Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania

Issue 55: February 14, 2022

photo courtesy of Lehigh Valley Economic Development Corporation

Inside this Issue:

Inflation Demons Still Alive: Annual Rate Hits 7.5

Inflation’s Duration: Imminent Relief or Ongoing Grief?

Selling a Dwelling: Will a Higher Mortgage Rate Spell Trouble for Real Estate?

Border Crawl: A Canadian Trucker Brigade Blocks U.S.-Canada Trade

Where to Draw the Line? How a City’s Fate Depends on Who Governs Where

The Road to Rising Riches? Will Technology Boost Productivity?

Hollywood Hit: The Story of Pixar, Featuring the Legendary Steve Jobs

The Economics of Municipal Governance: Who Makes the Decisions Where?

And this Week’s Featured Place: Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania, Eastern Inland Empire

An Econ Weekly Discussion of This Week's Issue

LISTEN HERE

Quote of the Week

“Right now, there is so much more demand [for housing] than there is available supply.”

- Toll Brothers CEO Doug Yearly, speaking on the “Exchanges at Goldman Sachs” podcast

Market QuickLook

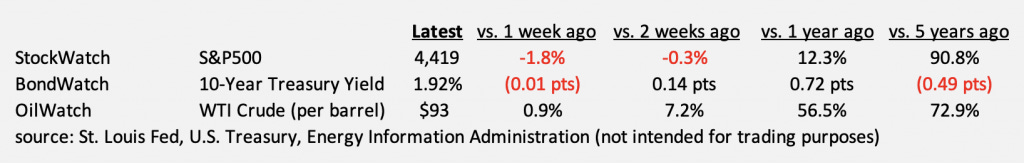

The Latest

No surprises this time. The Labor Department’s January jobs report, remember, came in much better than expected. Its January inflation report, however, delivered more of what America was uncomfortably anticipating: Additional evidence of dangerously rising prices.

How dangerous? The Consumer Price Index (CPI) showed prices up 0.6% from December to January, identical to December’s rise but down a bit from the steeper jumps seen in November and October (0.7% and 0.9%, respectively). On an annual basis, January’s CPI was up 7.5%, the largest increase since early 1982. At that time, Fed chairman Paul Volcker was prosecuting a storied and ultimately victorious war against inflation.

Does current Fed chairman Jay Powell want to fight that same war? Volcker’s dragon slaying came with heavy collateral damage, namely a steep recession to start the 1980s. Inflation, though, would never meaningfully rear its ugly head again… until 2021. Volcker’s war, importantly, was waged after a near decade of disruptive price instability, and with CPI growth at times nearly double the rates of today. Inflation during the Volcker years, moreover, was clearly a monetary phenomenon, as the late Milton Friedman said inflation always and everywhere is. Does that hold true today? Is the current inflation likewise about too much money chasing too few goods? Well, yes—there’s more demand for cars, for example, than there are cars being produced. So the price of cars is up. But the under-production itself is a supply chain phenomenon, not a monetary phenomenon. Which begs the question: Should Powell tighten money to curtail demand, bringing it closer in line with depressed supply? Or maybe that’s unnecessary. Maybe businesses will soon boost supply on their own, following a mere transitory period of virus-induced disruption?

Powell, to be sure, thought the transitory phase would last just a few months. But he nor anyone else anticipated Covid’s resilience, first with the delta wave last fall, then with the omicron wave this winter. The supply side of the economy, alas, remains greatly disrupted in early 2022—still not enough semiconductors, not enough labor, not enough port capacity, and so on. In one sense, Powell and his colleagues on the FOMC have already made up their minds: They’re already ending their loose-money bond buying policy. And they’ll almost certainly start tightening with an interest rate hike in March. But how much? A quarter point? A half point? A full point? What about subsequent meetings? Should the Fed not even wait for its March meeting and start hiking sooner? Such are the questions dominating the discourse of Wall Street right now.

One voting FOMC member, St. Louis Fed president James Bullard, appeared rather Volcker-like in expressing hawkish preferences this week. That helped boost the 10-year government borrowing yield above 2% for the first time since 2019. Yields retreated later in the week, however, as other Fed officials spoke more dovishly. So far this year, Treasury yields have risen most for shorter-duration borrowing. The two-year note, for example, is up 0.72 points from the start of the year, while the 30-year bond is up just 0.23 points.

What does this mean? Interpreting Treasury yield curve patterns (the cost of government borrowing across different periods of time) is a Wall Street obsession. Currently, the more muted movements for farther-out borrowing suggests investor bearishness about the longterm outlook for the economy. Why else would anyone lend so cheaply over 30 years? But a key point to keep in mind: Lenders lend to Uncle Sam for many reasons beyond just growing their wealth. They buy long-dated Treasuries for safety, for regulatory compliance, to influence exchange rates, etc., especially since the last financial crisis (when new regulations emerged and many assets perceived as safe proved otherwise). Maybe that’s why there’s so much demand for long-dated Treasuries, never mind America’s economic prospects. And to be clear, what happens in the Treasury market reverberates across the global lending landscape, influencing borrowing costs everywhere.

Alright, back to the January inflation numbers: Used vehicles stole the show with a 41% y/y price surge. Energy of all kinds rose by double digits. Food prices rose 7%. Housing inflation seemed comparatively tame at just 4%, though that’s still double the Fed’s overall target. Housing costs, keep in mind (both rents and owner equivalent thereof), represent a full third of the overall CPI index. And it’s a category that seems to have more upward momentum than say, used cars, which will certainly get cheaper as more semicons become available (which GM says they are). Note that new and used vehicles alone now account for a sizable 8% of the CPI index, after a re-weighting to reflect 2019 and 2020 spending patterns.

If the Fed does respond with aggressive rate hikes, the immediate risk is a housing slowdown. Homebuilders continue to feel good about demand (see the “Sectors” section below). But mortgage rates are already on the rise, and two Bloomberg columns last week raised some alarms. Gary Shilling and Mark Gongloff authored separate articles pointing to decreasing affordability, rising homebuilding activity, the end of Fed mortgage-bond buying, a return to city apartments, ongoing increases in construction costs and overall inflation’s impact on people’s ability to fund a down payment.

Oil isn’t helping. Prices rose again last week, with ominous implications for aggregate demand. Federated Global Investment, for one, estimates that every one penny increase in gas prices drops U.S. consumer spending by $1.2b annually. Walmart, incidentally, said long ago that the best predictor of its in-store sales is the price of gas.

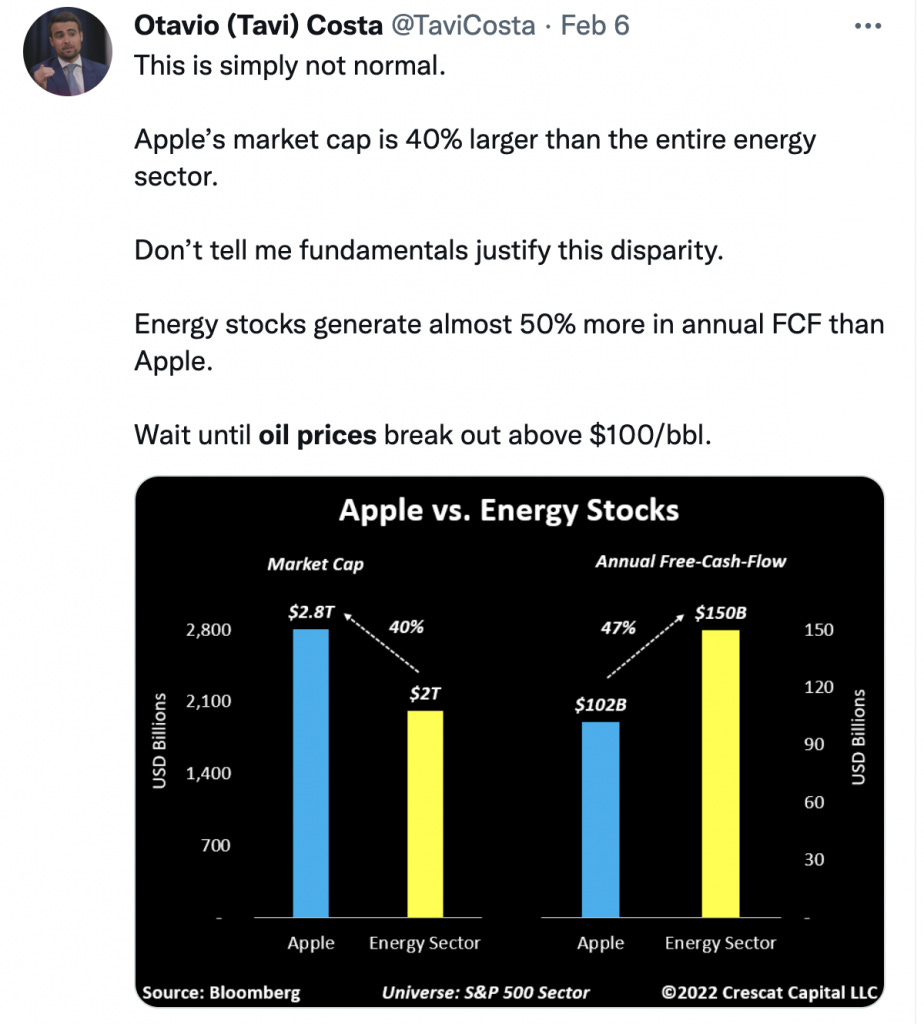

Oil’s steady upward March added pressure to stocks. They indeed fell again, with the tech-heavy Nasdaq index now down 14% from its November high. Rising interest rates, investors reason, make it wiser to bet on companies generating cash now, not promising cash years into the future. Tesla, for one, with its nebulous visions of robot taxis and robot factory workers, no longer looks quite so appealing.

Speaking of the auto sector, there’s a new frustration, this time involving Canadian trucker protests disrupting movements of supplies across a key border crossing. The airline sector, meanwhile, is consolidating again, this time with a proposed tie-up between the two low-cost carriers Spirit and Frontier. Nvidia, by contrast, officially abandoned its takeover of ARM. Peloton, a darling stock during the height of the pandemic, has a new leader amid distress. Disney, better positioned for the post-Covid world, continues to add streaming subscribers, lured by new characters like Bruno and old acts like the Beatles.

But we won’t talk about Bruno. Let’s talk about Washington, where federal debt now tops $30 trillion, or to be more precise $30,036,167,906,443.70. The House of Representatives passed a bill that would attempt to stem losses at the Post Office—it lost nearly $5b last year. And back at the Labor Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, the big CPI report everyone was talking about was accompanied by a separate report, this one monitoring workers and their inflation adjusted earnings.

Good news on that front: Real hourly earnings rose from December to January as nominal earnings rose 0.7%, a wee bit ahead of that 0.6% CPI inflation rate. Two other government reports of note from last week: The Census said December revenue for U.S. wholesalers—that’s a large group including distributors of oil, pharmaceuticals, groceries, electrical equipment, etc.—rose slightly from November and 22% y/y (higher prices account for much of the increase). And the Bureau of Economic Analysis said the U.S. trade deficit hit $81b in December, and $859b for all of 2021. For the record, America’s largest exports include pharmaceuticals, autos, aircraft, oil, gas, semiconductors, medical equipment, telecom equipment, soybeans and meat. Its top imports include oil, autos, computers, cell phones, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals and toys.

This week’s issue is hitting your inbox a few hours before Super Bowl kickoff. Rams or Bengals? In any case, enjoy the game (and the commercials). And once that’s done, you’ll be ready for another week of insights on the economy, not least the latest earnings report from Walmart, America’s largest company by sales. Walmart will report on Thursday. Also this week: updates on retail sales, import and export prices, business inventories and housing starts. The Fed’s new number two Lael Brainard will deliver a speech about central bank digital currencies. And joining Walmart on the earnings stage: Nvidia, Cisco, Marriott, Airbnb and more. Oh, and happy Valentine’s Day.

The Inflation Debate

Reasons Why Inflation Will Soon FALL

· With omicron fading, the economy seems set to normalize, ending supply chain disruptions and labor shortages

· High prices are a cure for high prices: As costs spike, consumers will spend less, forcing companies to eventually lower prices; wage gains, importantly are not keeping pace with consumer price increases

· The semiconductor shortage, a key reason for the superspike in motor vehicle prices, is already easing, according to GM for one. Rising auto prices have been a significant driver of inflation throughout the pandemic

· Government support for the economy is sharply receding. On the fiscal side, the impact of emergency measures like stimulus checks is fading, and income support measures like child tax credits and farm relief have ended. On the monetary side, the Federal Reserve is abruptly shifting from stimulative bond buying to interest rate hikes

· Household savings, though still elevated, is steadily declining, especially among lower income Americans with high propensities to consume; companies like PayPal have already in fact seen signs of people spending less

· Also weighing on demand this year are declining asset prices—stocks and bonds are both down. So are crypto assets. Will housing prices be next?

· A demand shift back to services will put downward pressure on goods demand, and by extension goods prices; think of a television set or a computer, prices for which have been steadily declining for decades

· The pandemic labor shortage led to heavy business investment that could result in technologies that lower prices. According to the BBC, the use of robots in North America has increased by 40% since the start of the pandemic, spreading well beyond the auto sector

· An already strong dollar, which will get another lift with rising interest rates, lowers the price of imports; a stronger dollar is also often correlated with cheaper oil over time

Reasons Why Inflation Will STAY HIGH

· High commodity prices, especially for energy and food, are rippling through the entire economy; the price of oil, for one, has steadily increased even before activities like office commuting and global air travel have fully recovered; there’s also the geopolitical tensions involving the oil power Russia

· Covid is not over! In China, America’s largest trade partner, factories, ports and even entire cities are shutting down in accordance with the country’s “Zero Covid” strategy. That promises to lift prices for imported goods

· Labor markets are still tight and there’s no turning back from wage hikes; many older workers have retired early; labor shortages in key sectors like health care and transportation, moreover, pre-date the pandemic and won’t get any better given record low population growth and tighter immigration curbs

· One earlier means of keeping prices low involved finding low-wage labor abroad; that’s harder to do now because of demographic trends (China’s workforce has started shrinking for example) and a preference for reshoring and nearshoring to build more resilient supply lines

· Corporate America has merged its way to formidable pricing power; in some industries like housing, severe supply shortages point to ongoing upward price momentum

· The green energy transition won’t come free; without cheap hydrocarbons, prices throughout the economy will inevitably inflate in the short to medium run

· As demand shifts to services, housing rents, mortgage costs, elective health care procedures, air travel and dining out could all see price gains; housing in particular seems almost sure to continue its upward march, especially with rents rising

· According to the latest New York Fed Survey of Consumer Expectations, Americans now anticipate prices to be up 6% one year from now. That makes workers more likely to demand higher pay to offset the increase. And that in turn risks a 1970’s-style upward wage-price spiral

· Banks have ample capacity to lend; if household savings run down, expect credit card lending and spending to rise. Translation: Greater demand to push up prices

Companies

Tyson Foods: When Americans of a certain age think Tyson, they might recall a former heavyweight boxing champ. But it’s Tyson Foods, not Mike Tyson, that punches above its weight in chicken, pork and beef processing. Based in northwest Arkansas not far from the Walmart empire, Tyson said in its Q4 earnings call that it’s managing through the challenges of higher labor costs, higher transportation costs and production shortfalls relative to the strong demand for its products. It’s no surprise given these conditions, that prices are up. “With these higher costs, we work closely with our customers to achieve a fair value for our products. As a result, our average sales price for the quarter increased 19.6% relative to the same period last year.” As it happens, meat processors are near the top of the list of sectors consumer advocates view as over-consolidated. Do companies like Tyson have too much pricing power? Do antitrust enforcement measures loom?

Lithia Motors: What’s an example of a sector that’s by contrast still very fragmented? “Unlike other retail sectors, automotive retail is totally unconsolidated,” said Lithia’s CEO Bryan DeBoer. The company, based in Oregon, is buying other dealerships to achieve economies of scale in auto retailing, a sector it says is worth some $2 trillion. That includes used car sales, new car sales, aftermarket servicing and financing. Lithia’s Q4 gross profit per used vehicle, by the way, jumped 37% y/y, reflecting a supply-constrained market. Gross profit per new vehicle increased 84%. Even in a fragmented industry, alas, car dealerships have considerable pricing power right now. The primary reason, of course, is the crippling shortage of semiconductors.

Tweet of the Week

Sectors

Housing: On the “Exchanges” podcast produced by Goldman Sachs, Toll Brothers CEO Doug Yearly recalled how market conditions for home builders looked solid on the eve of the pandemic. On the demand side, millennials were approaching their prime home buying age. On the supply side, the U.S. had built “significantly” fewer houses in the 2010s than in each of the prior four decades. Then came Covid in March 2020. Toll Brothers stock price plummeted. But already by May, signs of a pickup were visible. And starting in the summer of 2020, all the way through to today, “we have experienced the hottest housing market I have seen in my 32 years at Toll Brothers.” Low mortgage rates added to the momentum. Existing home inventory dropped as people didn’t want shoppers entering their homes during Covid. As home prices spiked, homeowners found themselves with more home equity to trade up to a more expensive home. The stock market boom made potential home shoppers wealthier. Urban dwellers and remote workers sought homes in the suburbs. “It was a Category Five hurricane that turned into a perfect storm for our industry.” And “it feels like it’s going to continue.” A recent rise in mortgage rates isn’t having an impact, Yearly says, and probably won’t until they rise another point or so. Longer term, more people will likely seek second homes as houses double as offices. The country’s housing stock is aging. Separately, he says the biggest constraint on homebuilding is land supply, which is “very tedious” to secure, often involving an approval process of three to five years. At the same time, homebuilders—who outsource most of their construction to legions of small subcontractors—have been very slow to adopt new technology. Houses, he said, are built the same way today as they were 30 years ago.

Markets

Labor: A Brookings Institution panel on immigration last week featured Tara Watson and Kalee Thompson, authors of the new book “The Border Within: The Economics of Immigration in an Age of Fear.” Currently, the U.S. is home to 45m foreign-born residents, or 14% of the total population—a similar percentage as in 1900. Roughly 11m of those 45m are undocumented. And about two-thirds of these 11m have been here for more than ten years. The most common way they arrive is not through illegally crossing the border, but rather entering legally and then illegally overstaying their visa. One speaker at the event, Alex Nowrasteh of the Cato Institute, described how enforcement mechanisms like e-Verify aren’t effective, because even politicians who get elected by talking tough often look the other way to avoid harming their local economies (and major employers in their districts). The bottom line, everyone on the panel agreed, is that demand to live and work in the U.S. greatly exceeds visa supply, which creates big incentives to come illegally. Policies on legal immigration are still largely based on a framework created by Congress in 1965, with family members prioritized. The current number of visas was set in law by Congress in 1990, and thus largely out of a President’s control. There’s some discretion, however. On Jan. 27th, the Biden Administration’s Homeland Security department announced 20,000 additional H-2B visas, designed for U.S. employers (non-agricultural) that are facing “irreparable harm without additional workers.” Roughly two-thirds of the new visas—all temporary—will go to returning workers who already held H-2B visas in the past. The rest will go to migrant workers from Haiti, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

Labor: One interesting idea that came up in last week’s Brookings Immigration Forum: A policy that ties the level of immigration to the old-age dependence ratio, which measures the number of workers per retiree. The U.S. should issue enough new visas, in other words, to ensure that this ratio holds steady. It’s one way to ensure the future viability of the Social Security system, America’s popular national pension plan for seniors. Absent any changes, the U.S. workforce will soon be too small to support the country’s fast-growing number of retirees.

Government

Housing Policy: The title of a new book by Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page Aldern says it all: “Homelessness is a Housing Problem: How Structural Factors Explain U.S. Patterns.” They make the case that cities with high levels of homelessness are not those with high poverty rates but rather high housing rents and low vacancies. Colburn, talking on the “New Books Network” podcast, gives the example of wealthy cities like New York, San Francisco and Seattle, all with expensive housing and high homelessness. Conversely, cities like Detroit, St. Louis and Cleveland have much higher rates of poverty but lower rates of homelessness.

Local Government: Crabgrass Frontier, a book published by historian Kenneth T. Jackson in the 1980s, traces the rise of suburbia in 19th and 20th century America, citing forces like the advent of the automobile, cheap oil, the abundance of cheap land surrounding cities, federal subsidies for highways and single-family housing, tax deductions for buying a home on credit, new methods of mass-producing single-family homes and policies that encouraged Whites to leave urban centers in the wake of the Great Migration of rural Blacks to northern cities (starting around the time of World War I). Also influential was the 1954 Supreme Court decision ruling segregated schools unconstitutional.

Local Government: As suburbs developed, Jackson explains, a major dilemma about political governance arose, one in fact rooted in early American history. “On the one hand, democracy seems to call for government to remain small and close to the people. On the other hand, efficiency and the regional character of many contemporary problems point to the necessity of government that is metropolitan in authority and planning.” Where, in other words, to draw political boundaries? How much control should individual neighborhoods have? Should services like policing, schooling and water management be provided at a county level? A city level? A neighborhood level? There’s nothing in the U.S. Constitution that addresses such questions. In some places, cities have the right to annex unincorporated territory without a popular vote. Examples have included Dallas, Indianapolis, Oklahoma City and Jacksonville. Miami and Nashville are examples where lots of responsibilities lie at the county level. St. Louis is an example where the city largely governs itself but most of the wealth is in separately governed suburbs (for more on the governance of greater St. Louis, see the Jan. 11th, 2021, issue of Econ Weekly). As the Newark Star Ledger recently noted, New Jersey has roughly 600 school districts, each with varying tax resources. Florida by contrast, a much larger state, has just 74. Its public schools are managed at the county level, which incorporates a broader array of household incomes.

Local Government: This question of who governs what and where within a city is front and center right now in Atlanta. There, a “cityhood” movement is underway, described by Bloomberg as a local push by wealthier areas for “more control over land use decisions and tax policy: essentially, the power to control what gets built and how public dollars get distributed.” But it adds “Poorer neighborhoods that have suffered from disinvestment end up with even less resources for economic development in their localities. These neighborhoods typically don’t have the incomes, property ownership and political influence to start their own cities.” Last week, Georgia’s legislature said it would not advance legislation to allow the Atlanta neighborhood of Buckhead to vote on seceding from the city. The area—wealthy and majority-white—accounts for about 20% of Atlanta’s population but about 40% of its tax revenues.

Places:

Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania: Billy Joel understood. “They’re closing all the factories down… and it’s getting very hard to stay.” So sang the singer in “Allentown,” his 1982 portrait of American deindustrialization. By the mid-1990s, even the mighty Bethlehem Steel was largely gone, leaving northeastern Pennsylvania limping into the new millennia with bleak economic prospects. Sure enough, many of America’s old industrial regions never did regain their footing, some still looking for answers in the 2020s. Not the Lehigh Valley though. If Billy Joel were to write a song about Allentown today, it would tell of warehouses and health care facilities opening up, making it hard for many jobseekers not to come. Allentown and its neighboring cities of Bethlehem and Easton aren’t exactly replicating the spectacular booms of Sun Belt superstar metros like Austin, Orlando or Nashville. The Valley’s combined metro area saw population grow just 3% during the 2010s (Austin grew 29%). But don’t let that mask what’s been a remarkable economic renaissance, one less heralded but no less impressive than Pittsburgh’s revival in Pennsylvania’s west (see Econ Weekly’s Oct. 14th, 2021, issue). Unlike Pittsburgh, the Lehigh Valley isn’t on anyone’s list of 21st century information technology hubs. It has nothing quite comparable to Pittsburgh’s leadership in artificial intelligence and autonomous driving. Yet the Valley—Pennsylvania’s third largest metro after Philadelphia and Pittsburgh—punches above its weight in advanced health care and life sciences. The health care sector is the area’s largest employer. Manufacturing is still very much alive in the Valley, accounting for 16% of economic production, compared to 13% nationally. It’s not making steel anymore. It’s instead making transportation equipment (Mack Trucks has a factory near Allentown), pharmaceuticals, medical devices, industrial products and even crayons—Crayola is headquartered in Easton. These days, supporting a manufacturing economy isn’t about supplying cheap labor, but rather skilled labor. That underscores the importance of the Valley’s colleges, most importantly Lehigh University, renowned for its engineering program (the late auto exec Lee Iacocca is a famous alum). The school is also one of the region’s top employers. But can education, health care and modern manufacturing really bury the ghosts of steel? According to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Bethlehem Steel alone employed 300,000 people nationwide during World War II. The manufacturing sector, in fact, continued to decline well into the new millennia, shedding more than 2,000 jobs between 2001 and 2007. By then, however, a new engine of economic growth was taking shape across America, one exemplified by California’s Inland Empire. There, a hub had emerged for sorting, storing and distributing the tsunami of goods entering the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Land and labor are much cheaper there than in and around pricey L.A. Yet it’s close enough, not just to handle L.A.’s imports but all the e-commerce deliveries bound for America’s second largest consumer market. But what about America’s largest consumer market? What location had low enough costs, sufficient highway access and ample enough land to conveniently distribute goods into and out of the New York City metro, not to mention nearby Philadelphia? The Lehigh Valley fits the bill, transforming into an east coast Inland Empire. From 2000 to 2018, the area’s jobs in transportation and utilities more than doubled from 12,000 to nearly 30,000. And that was before the pandemic-era surge in e-commerce. This past holiday season, Amazon alone recruited 800 additional seasonal workers at its multiple Leigh Valley facilities. FedEx has one of its largest ground facilities worldwide near Allentown. Job offers are everywhere, screaming from billboard after billboard along highways running into and out of the city. Route 78 runs straight to New York, just 90 miles to the east. Others run straight into Philadelphia, 60 miles to the south. Warehouse construction sites are everywhere. So are trucks moving along the highways—not always to the liking of local residents. Last May, the New York Times profiled the Valley’s e-commerce boom, noting that “manufacturing jobs in the Lehigh Valley pay, on average, $71,400 a year, compared with $46,700 working in a warehouse or driving a truck.” Still, that’s attractive in a country where good jobs for non-college graduates are increasingly scarce. They’re jobs, furthermore, where pay has risen sharply during the pandemic, and which can’t be outsourced to Mexico or China—though robots and autonomous trucks are a threat. Like pretty much everywhere else across America, it’s not easy finding enough warehouse workers and truck drivers right now. Affordable housing is another local malady mirroring national trends. According to the Greater Lehigh Valley Realtors, home prices spiked 18% last year. Billy Joel would never have imagined that in the 1980s, never mind the early 2000s. The Valley has even become a magnet of sorts for immigrants, especially Latin American and Caribbean families priced out of New York City and New Jersey (in 2016, 12% of the Valley’s population identified as Puerto Rican). Casino gambling has drawn nearby tourists—Sands Bethworks Gaming is the metro area’s third largest non-government employer. Downtown revitalization has drawn newcomers. And the Lehigh Valley Economic Development Corporation (LVEDC) highlights the Covid-era emergence of “super commuters” with hybrid jobs in cities like New York and Philadelphia. Amtrak, incidentally, is pushing for a direct rail link to New York. Allegiant, meanwhile, America’s most profitable airline, is expanding air service to Florida from Lehigh Valley’s main airport. Time to write a new song, Billy. (Sources: U.S. Census, U.S. HUD, Morning Call, Amtrak, LVEDC).

Abroad

Canada: Record low housing supply. The prospect of rising interest rates. Home prices pushed beyond the reach of many budgets. Sounds like the U.S., no? But this is from CBC News describing British Colombia, Canada. America’s frustrations with underbuilding, restrictive zoning and permitting, lack of technological progress in construction, etc., are understandable. But complicating the diagnosis is the fact that other countries like Canada are experiencing the same housing shortages. Those same forces, it seems, are a global phenomenon, afflicting many urban areas in developed economies. The latest Economist, incidentally, has an article profiling the housing shortage in New Zealand.

What are the most expensive cities in the world? The Economist Intelligence Unit put Tel Aviv, Israel, atop its latest Worldwide Cost of Living ranking. Next were Paris, Singapore, Zurich, Hong Kong, New York and Geneva.

Foreign Exchange Trends

Looking back

Pixar: Alvie Ray Smith, co-founder of Pixar, tells the story of the company’s origins in his book “A Biography of the Pixel.” Pixar became a household name in 1995 when it debuted the wildly successfully computer-animated film Toy Story. Smith himself began his career at Lucasfilm, the production company owned by Star Wars creator George Lucas. There, working for the studio’s Computer Graphics Group, Smith helped develop the Pixar Image Computer. It wasn’t terribly useful at the time, though it did generate some special effects in movies produced in the 1980s, notably Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, and Return of the Jedi. It wasn’t much, but Smith and other pioneers of the technology knew that with Moore’s Law promising great leaps in computing power, the technology would eventually open the door to a new art form: the creation of digitally animated movies. As it happened, Lucas was forced to divest much of his company as part of a divorce. Smith and others went out on their own and nearly partnered with General Motors subsidiary EDS, a company founded by Texas billionaire and future presidential candidate Ross Perot. The deal fell through, however, so the struggling startup Pixar, based in the San Francisco Bay Area and founded in 1986, turned to Steve Jobs. Jobs, who had just been ousted at Apple, eventually agreed to buy the whole company from its employees. Pixar quickly earned some revenue making short films, which became progressively more sophisticated as computing power scaled. In 1989, it helped create a scene for Disney in “The Little Mermaid.” Two years later, Jobs struck a deal with Disney to produce an entire movie, which would become Toy Story. Jobs became a billionaire with Pixar’s 1995 IPO. In 1996, Disney bought the company for $7b. Since then, Pixar has produced hit movies like Bug’s Life, Finding Nemo, The Incredibles and several Toy Story sequels. Other digital animation companies, meanwhile, followed its path, most importantly Dreamworks, the creators of movies like Shrek and Madagascar.

Looking ahead

Interest Rates: Harvard’s Jason Furman, interviewed on Ezra Klein’s New York Times podcast, doesn’t forecast a coming era of high interest rates. But if wrong, he warns, that could spell lots of trouble. Assessing the U.S. economy’s prospects going forward, Furman says “probably the biggest risk other than the virus is that our economy is built around low interest rates.” A lot of people, he explains, have a lot of money riding on the bet that interest rates will stay low. So does the government. Total federal debt just crossed $30 trillion, and while much of that was helpfully financed at very low interest rates, Uncle Sam might not be so lucky when borrowing to finance future obligations.

Technology: In that same interview, Klein asked Furman whether he thinks the economy will see big gains in productivity from new technologies like mRNA vaccines, renewable energy, artificial intelligence and so on. The prior decade, keep in mind, saw minimal productivity gains (to the extent these can be measured anyway—Robert Solow famously said he could “see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics”). Furman, alas, doesn’t sound terribly optimistic. He cites the example of an incredibly sophisticated robotics breakthrough that can pick fruit. That wouldn’t move the GDP needle much because the harvesting of much more economically significant crops like corn, soybean and wheat was already mechanized long ago. Even in medicine, recent gains in fighting cancer for example, have been impressive but incremental. He's a skeptic on the crypto economy too. In 2016, Northwestern’s Robert J. Gordon published a much-discussed book called the “Rise and Fall of American Growth.” It argued the point Furman is trying to make: That innovation was much more economically significant in earlier eras of American history. Breakthroughs like electricity, automobiles, jet airplanes and indoor plumbing were far more revolutionary to people’s lives than the breakthroughs of the past few decades.

Renewable Energy: Solar and wind power is now cost-competitive with natural gas, states Eurasia Group’s Robert Johnston, interviewed on the Energy Now podcast. But what happens when the sun isn’t shining, and the wind isn’t blowing? That’s currently the chief challenge with renewable power—its intermittency. One solution is building backup generation when needed, using natural gas. Using batteries to store excess power generated by solar and wind is another solution. But now you’re losing the cost competitiveness with just using natural gas. Johnston says the three big drivers of U.S. natural gas demand are 1) heating and cooling, 2) producing electricity and 3) industrial use. There’s also global demand for America’s gas, which can be exported abroad by sea when liquified.

Interested in helping develop and market Econ Weekly? I’d love to hear from you. Email me at jay@econweekly.biz. And be sure to sign up for my free newsletter about the North American railroad industry: