Place of the Week: Hartford, Connecticut

Econ Weekly Free Edition (Jan. 24, 2022)

This Week’s Entire Issue Free to Read

Issue 52: January 24, 2022

Inside this Issue:

Much Ado in 2022: An Eventful Start to the New Year

The Activision Decision: Microsoft’s Play for Game Fame

Mortgage Baggage: Rising Rates at Real Estate’s Gates

When Covid Came: How the Fed Reacted when Markets Buckled

Lease Lightening: Health Care, Distro Firms Need More Space

State of the States: Governors Enjoying a Fiscal Fiesta

Bullish or Bearish: A Debate About China’s Economy

Hauling without Humans: The Future of Autonomous Trucking

And this Week’s Featured Place: Hartford, Connecticut, Enduring Beyond Insuring

Quote of the Week

“We are shedding our image of being uneducated, dusty, poor, and backward. We are shedding our image of being bankrupt and a place business cannot operate because of our legal system. Together, we will continue to shed the dead weight that has been holding us back for years so we can continue to climb higher and higher on our journey to prosperity in West Virginia.”

-West Virginia governor Jim Justice

Market QuickLook

The Latest

How’s this for an eventful start to 2022? Stock prices, bond prices and crypto prices are suddenly plummeting. Oil prices are up 13% just since New Year’s Day. Unemployment claims are up. Omicron continues to rattle labor markets. American workers, according to just-released figures, are earning just 3% higher pay, at a time of 7% higher prices. Oh yeah, and Europe is inching toward war.

The Fed has lots to consider as it holds its first policy meeting of 2022 this week. Don’t expect any rate hike moves just yet. But all signs point to hikes at the next meeting in March. Just a quarter-point hike? What about subsequent hikes later in the year? Might the Fed even start shrinking its portfolio of securities before year end? These are surely questions Fed chair Powell can expect at his press conference on Wednesday.

A word about those falling stock prices: Getting hit hard are the darlings of the pandemic, like the tech champions of Silicon Valley and Seattle, along with stay-at-home winners like Peloton and Netflix. The market gods, meanwhile, are raining on the SPAC parade. Having a great start to the year, by contrast, are oil stocks. As for crypto assets—no strangers to extreme volatility—last week’s price declines were breathtaking. Bitcoin, for one, has lost roughly a third of its value since the start of the year. The decline is closer to half for Ether, the currency used on the Ethereum blockchain. Will this have a meaningful wealth effect on consumer sentiment?

Now a word about falling bond prices. Ten-year U.S. Treasury yields briefly touched as high as 1.87% last week before falling back to 1.75%. The upward push shouldn’t seem too surprising with inflation running so hot and the Fed poised to lift overnight rates in March. A few things to keep in mind though: Ten-year rates jumped to similar levels early last year, only to retreat later on. Also—this is important—shorter-term Treasuries in the 1-to-5 year timeframe are rising significantly more than longer-term Treasuries in the 7-to-30 year time frame. Graphed over time, this makes for a flatter-looking yield curve, often a signal of pessimism about the economy’s longer-term prospects. If the curve inverts (meaning short rates get higher than long), history suggests a looming recession.

Turning to the labor market, there’s one important caveat to the decline in inflation-adjusted wages. In some areas of the economy, including transportation jobs, real wage gains are exceeding inflation. Still, with overall earnings eroded by rising prices, the future of consumer spending lies in doubt. Household finances, to be sure, still look robust with elevated savings, modest liabilities and gains still in tact from a long bull run in stocks and housing prices.

Speaking of which, what happens to housing prices as rising interest rates make mortgages more expensive? It’s a potential headwind for what’s a giant part of the economy. That said, mortgage rates will remain historically low barring an extreme spike. Existing home sales by the way, increased nearly 9% in 2021, according to the National Association of Realtors. But December sales declined 5% from November. Selling prices, meanwhile, keep drifting upward, to levels 16% above where they were a year ago. Mercifully, construction of badly needed new homes is on the rise, up nearly 7% y/y in December, according to the U.S. Census. The increase is entirely driven by multi-family housing, with single-family home construction still more affected by labor shortages, broken supply chains and rising input prices.

There was a big merger announcement last week. Microsoft will buy video game champion ActivisionBlizzard for $69b. To put that in context, the largest merger deal of 2021—that involving AT&T’s Warner Media and Discovery—was worth about $43b. The largest U.S. merger deal ever (AOL-Time Warner) was $182b. As the latter proved, not all mergers go smoothly. But Microsoft hopes to make it worthwhile by fortifying its might in the massive video game sector, which makes even Hollywood look tiny. It’s already a big player in the space with Xbox. And if all goes as planned with the Activision deal, it will become the world’s third largest gaming company after China’s Tencent and Japan’s Sony. The deal positions it to build a presence in the newly emerging metaverse as well, where people engage in activities once reserved for the offline world, from attending meetings to buying real estate. Don’t sleep on this fact: There are 3b people actively playing video games today. Three billion people (!) in a world with 7b people total.

Ironically, Microsoft is today the least likely tech target of antitrust regulators, who decades ago considered it public enemy number one. That’s not to say, however, that the Activision deal is clear of any obstacles. Momentum for a new approach to competition law continues to build, one that looks beyond the Robert Bork-inspired standards embraced since the 1980s. A bill progressing through Congress, meanwhile, would prevent tech giants from favoring their own products on their websites.

Some other news to know: The auto industry’s production problems are getting better, according to GM’s chief economist, appearing on a Moody’s Analytics podcast. The nation’s rollout of 5G telecom, considered critical infrastructure for the evolving tech economy, stumbled amid safety concerns among airlines. Ohio won a massive development prize by luring Intel to the Columbus area, where it will build at least two new semicon factories. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, addressing the World Economic Forum, championed a “modern supply-side economics” that focuses on labor supply, human capital, public infrastructure, research and development and environmental sustainability. Democrats on Capitol Hill are seeking ways to salvage pieces of President Biden’s Build Back Better plan. In the earnings arena, more of the nation’s largest banks reported Q4 results, along with corporate titans like UnitedHealth, Procter & Gamble and the railroad Union Pacific (see our sister publication Railroad Weekly). Big Tech stands ready to report this week, with Microsoft getting things started on Tuesday. Some others on deck: Apple, McDonald's, Intel, Chevron, Verizon, AT&T, Boeing, Johnson & Johnson, Tesla, IBM, GE and Lockheed Martin.

Companies

United Healthcare, the nation’s largest health insurer, reported a drop in primary care visits and elective procedures during the early weeks of January, owing to the spike in Covid cases. Though cases are four times higher this January than last, United said hospitalization levels for its customers are similar y/y. Omicron, furthermore, appears less severe even for Covid patients that do require hospitalization. Length of stays are therefore shorter on average. Based in Minneapolis, United operates two distinct but complementary businesses, one essentially delivering care and the other insuring care. On the delivery side, pharmacy services account for a big part of its activities. In 2021, United generated a massive $223b in revenue, though just a 5% operating margin, down from 6% the year before. Customers include individuals, companies and governments. Strategically, a key goal is transitioning patients to what it calls “value-based care,” as opposed to fee-for-service care. It naturally has huge amounts of data, a big asset in the age of machine learning. All the while, it’s working to add new technologies and practices like virtual care. Its efforts are of national importance given its size, and given the epic inefficiencies, costs and market failures of the U.S. health care system. Interestingly, United said the pharmacy is where people have the most interaction with the health care system.

Travelers: According to the Congressional Research Service, United is one of more than 300 health and life insurers in the U.S., collectively generating about $600b a year in premiums. There’s another category of insurers too: The roughly 1,000 companies covering property and casualty losses—these also generate about $600b annually. According to a ranking published by AM Best, State Farm (Bloomington, Illinois) is the largest insurer of property and casualty, followed by Berkshire Hathaway (Omaha), Progressive (Cleveland), Allstate (Chicago) and Liberty Mutual (Boston). Next on the list is Travelers, based in New York City but large in what’s still called the insurance capital of America: Hartford, Connecticut (see Places section below). Travelers reported earnings last week, trumpeting record profits and excellent returns on its investments with help from exposure to alternative assets like real estate. The firm sells policies to individuals and companies, insuring homes, autos, property, bonds, legal exposure, workers’ compensation liabilities, cyberattacks, etc. Travelers did mention a rise in auto payouts as people drive more miles and costs for vehicle replacement and repairs increase. It also noted trends like rising highway fatalities, fewer people wearing seat belts and more accidents due to mobile phone use while driving. Looking ahead, Travelers sees lots of opportunity to improve earnings through machine learning, which can, for example, accelerate damage assessment and claim resolution in the wake of catastrophes. It also spoke of growing climate risks, noting that weather damage has been running above average in recent years.

Tweet of the Week

Sectors

Real Estate: Residential real estate is booming. Commercial real estate? Not so much. After all, look what the pandemic did to downtown office and retail space. Look what it’s done to hotels. But there are two bright shining lights for investors. Long Island attorney Michael Sahn, speaking on a panel aired by the Realty Speak podcast, calls attention to demand among 1) health care organizations and 2) distribution companies. There’s a seemingly “insatiable demand” for more space by hospitals, outpatient clinics (sometimes called ambulatory care clinics), research labs and medical schools. One hot trend is leasing health care organizations office and administrative space in suburban strip malls originally built for retail. It’s another manifestation, by the way, of health care consuming an ever greater slice of the U.S. economy (it’s now approaching 20% of GDP). As for distribution, the hot demand is for facilities catering to last-mile delivery. That’s of course associated with the boom in e-commerce. This includes real estate used for warehousing and the transportation associated with it. Just two other unrelated points mentioned during the panel discussion: Just 1,600 wealthy families in New York City pay 27% of all income taxes, creating a burden that’s encouraging some to leave for places like Florida. A Wall Street Journal report separately noted that New York State tax coffers are overflowing thanks to the boom on Wall Street. One developer, meanwhile, called low interest rates “rocket fuel” for the real estate industry, which begs the question: What happens now that interest rates are rising?

Public Health: Sadly, gun deaths in America reached an all-time high in 2020, according to the CDC. With 45,222 people dying of gunshot wounds, firearms became the 13th leading cause of death in the U.S., surpassing even vehicle accidents. The totals include both homicides and suicides. The states with the highest rates of gun deaths were Mississippi, Louisiana and Wyoming. The states with the lowest rates were Hawaii, Massachusetts and New Jersey. Why have gun deaths soared during the pandemic? There are lots of different theories, including the stress of disruptions like school closures and heavy job turnover. Some point to gun sales, which are at record levels.

Markets

Labor: A Goldman Sachs research report sees lots of positive productivity arising from pandemic-era work trends. Americans, the report estimates, now spend 600m fewer hours commuting each month. Perhaps 1.4m cashiers, sales clerks and office maintenance staff are no longer needed as downtown offices go unused. Many of these workers, the report says, will be reallocated to more productive jobs. With people working at home meanwhile, using their own offices and own equipment, Goldman sees some $300b worth of consumer IT and home office space now available for business use at no charge.

Stocks: What’s the best indicator of future stock market performance? Former JPMorgan Chase economist Alex Gurevich, who now runs Honte Investments, looks at the change in interest rates over the previous two years. If rates have dropped, that’s often followed by strong stock market performance, as was the case during the pandemic. When rates rose in 2016 and 2017, it sure enough preceded stock market losses in 2018. With interest rates now on the rise, it could herald a rough spot for stocks, though nobody can say yet if this month’s stock swoon will persist. Gurevich explained his thesis on the Market Champions podcast, hosted by college student Srivatsan Prakash.

Alternative Assets: On a different podcast—Macro Hive Conversations with Bilal Hafeez—Morgan Creek Capital’s Mark Yusko gave his thoughts on pensions and retirement saving. He thinks government and other pension fund boards rely too much on stocks and bonds, neglecting exposure to alternative assets like real estate, private equity and debt, commodities and even crypto (on which he’s very bullish). He adds that the traditional 60%-40% stock-bond allocation strategy no longer makes sense with bond prices likely to fall after a four-decade bull run.

Energy: In “Up to Heaven and Down to Hell,” a book about oil and gas fracking, author Colin Jerolmack notes how the U.S. is the only country in which a person’s legal property includes both all the air above and whatever lies in the ground below. This means landowners have exclusive rights to lease their property to energy companies looking for oil and gas. In a discussion on the New Books Network podcast, Jerolmack explains how this can be controversial when it comes to fracking in populated areas like western and central Pennsylvania. For example, leasing one’s land can yield financial rewards but can also cause irreparable harm to neighbors and communal resources like air and water. By the way, why do U.S. landowners have such expansive rights over what’s above and below their property? Jerolmack says the reason dates back to colonial days, when the British crown retained rights to anything valuable beneath the soil. After independence, Americans didn’t want any government—including their own—claiming such rights.

Government

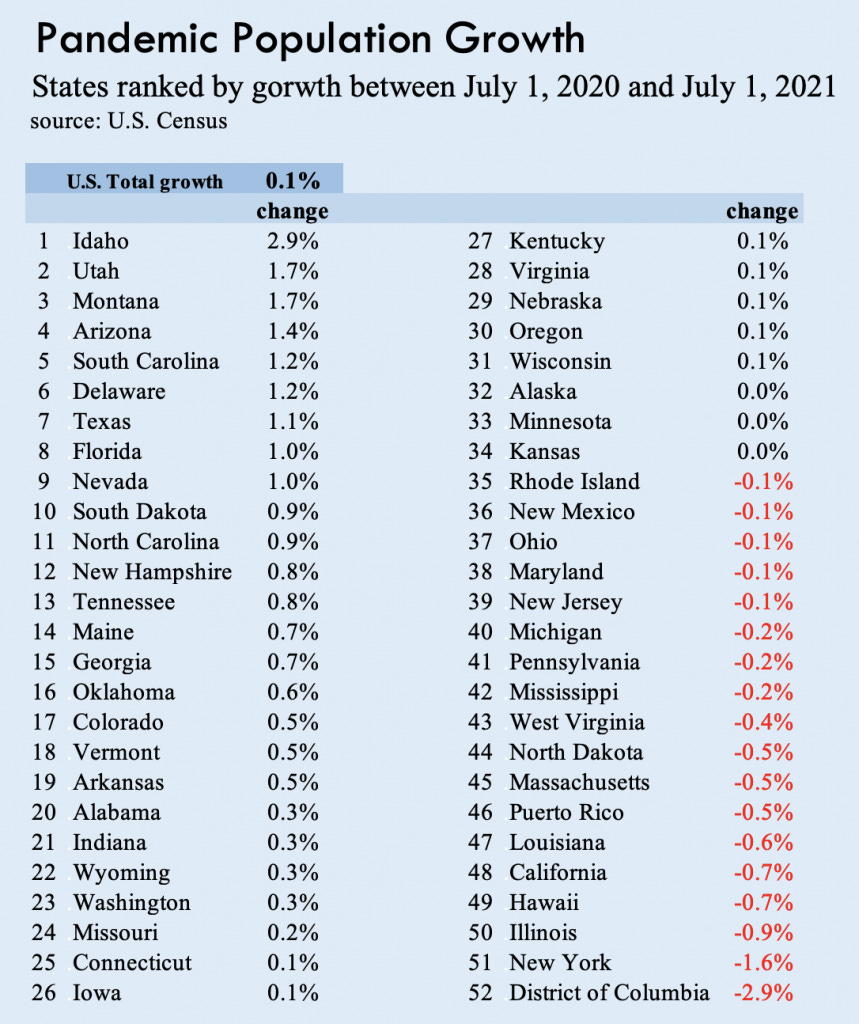

The States: Every January, most U.S. governors deliver a speech to their legislatures, highlighting achievements, priorities and goals. From a fiscal perspective, this year’s speeches were generally upbeat, thanks to a multitude of tailwinds for state budgets, most importantly federal aid and robust tax inflow. Indeed, most of what states tax—property values, retail sales, personal and business incomes, capital gains, etc.—are all rising. Public health, education, climate resilience, public safety, broadband access, infrastructure, affordable housing, taxes and job growth are universal themes discussed throughout the country. But speeches can feature more parochial matters too, such as Washington’s Jay Inslee pledging to address challenges to salmon fishing. Arizona’s Doug Ducey spoke of issues pertaining to water and border security. West Virginia’s Jim Justice delivered one of the more colorful performances, insisting his state was shedding an image of “being uneducated, dusty, poor and backward.” He has a point, with population trends stabilizing after a decade in which 43,000 people left the state. Last year, Justice said, 30 companies invested more than $1.1b in West Virginia creating 1,330 new jobs. One newcomer is Nucor, which will build a $2.7b state-of-the-art sheet steel mill. Automakers are expanding in the state too, as they are throughout the region between the Atlantic coast and the Mississippi River. Florida governor Ron DeSantis trumpeted his state’s robust population growth and refusal to restrict business activities in the name of public health. New York’s Kathy Hochul, by contrast, lamented the 300,000 people that left the state in 2020, “the steepest population drop of any State in the nation [and] an alarm bell that cannot be ignored.” Vermont’s Phil Scott evoked even starker population worries, representative of an aging and shrinking rural America that’s losing its ability to maintain public services. He said his biggest concern is “that for years, our working-age population and the number of kids in our schools had been shrinking unsustainably, creating deep economic inequity between the northwestern part of our state and everywhere else.” All 14 of Vermont’s counties are losing working-age residents, with the statewide workforce down by 30,000 since 2010. And “while the pandemic didn’t create this problem, it has made it much, much worse.” Governors naturally have different opinions about why people and companies move from one state to another. Some emphasize the lure of lower taxes and less regulation. Some say the key growth drivers are good weather, job opportunities and affordable housing. The pandemic, meanwhile, has made people more mobile thanks to remote working.

Debate

The China Power Project, part of the Center of Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), hosted a debate about China’s economic prospects and whether the pandemic has been an accelerator or a setback. Yes or no? You decide.

Yao Yang of Peking University argued that the pandemic will accelerate China’s economic development. After all, the nation quickly contained the virus after its original outbreak in Wuhan, allowing the economy to grow while the rest of the world was locking down. Today already, China’s GDP is larger than that of America’s when adjusting for purchasing power. Even without this adjustment, China is on pace to become the world’s largest economy as soon as 2028. During the pandemic, China’s exports have surged, reversing downward momentum caused by U.S. tariffs. Tesla is now selling 50,000 cars a month in China, where the total of electric vehicles is six times that of the U.S. It’s one sign that China is far ahead in adopting new technologies—in this case EVs—that will shape the coming decades. It’s also catching up in areas like artificial intelligence. In fact, the task of tracking people’s movements during the pandemic resulted in significant AI advancements. China is the world’s largest recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI). And most of its debts are domestic, easily rolled over to prevent major financial disruptions. [note: China said last week that its GDP grew 8% in 2021, and 4% for just the fourth quarter).

Gerard DiPippo of CSIS took a bleaker role of the pandemic’s impact on China’s economy, which already faced many headwinds. He points to the country’s recent energy shortages and plummeting property sales. The latter exacerbated a debt crisis among systemically important property developers, most famously Evergrande with its $300b pile of debt (roughly equivalent to the GDP of Finland). China’s household finances are worse off, with consumption still below pre-pandemic levels. Beijing in fact opted against a big fiscal stimulus that would have supported household spending, like it did after the 2008-09 financial crisis. Its stimulus this time was just 5% of GDP, compared to 25% in the U.S. Looking at combined household, corporate and government debt, this amounts to about 285% of GDP for both countries. But whereas much of America’s obligations are federal government debt-financed by highly liquid and valuable U.S. Treasuries, China’s debt is mostly held by local governments and state-owned enterprises dependent on central government loan guarantees. Besides, while the U.S. federal government increased its debt by about $5 trillion during the pandemic, the net worth of U.S. households simultaneously increased by $25 trillion. In the meantime, multinational firms appear to be shifting some production out of China to reduce supply chain risk. That will cost manufacturing jobs, which have been disappearing in China since 2014. Some foreign governments (i.e., Japan) are even subsidizing their companies to do so. Before the pandemic, China was working hard to reduce its dependence on net exports. But in 2020, they contributed more to GDP growth than in any year since 1997. All the while, China’s working-age population is shrinking. It faces growing diplomatic hostility from countries across the globe. It remains dependent on coal for energy. Its “Zero Covid” strategy is much less effective against new strains of the virus. Other economies are lifting border restrictions. And in the U.S., mRNA vaccines demonstrated technological leadership, while a $1b infrastructure package should boost the U.S. economy’s long-run potential.

Places:

Hartford, Connecticut: It’s one of the smallest states in the country. But Connecticut is also one of the wealthiest per capita. It helps that towns like Stamford and Greenwich are within commuting distance to New York City. These places also home to the largest agglomeration of hedge funds outside of New York, led by Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater Associates (AQR Capital, Viking Global and Tudor Investments are some others). The average wage for financial service workers in the area, according to the Stamford Advocate, is a princely $266,000. Moving eastward along the state’s coast toward Boston, you’ll find New Haven, home to Yale University. Still farther down the coast is New London, where General Dynamics builds multi-billion-dollar submarines for the U.S. Navy. Also along the coast are Native American casinos. Connecticut’s largest city Hartford though, isn’t on the coast. It’s located in the center of the state. And its economic picture is more complicated, not exactly reflective of Connecticut’s image as a prosperous land of money managers, Ivy League professors and Navy sailors. Hartford was, to be sure, once upon a time among America’s wealthiest cities. But that was during the late 19th century, when it evolved into ground zero for the insurance industry. That distinction still holds true today, topping even Des Moines, Iowa, in insurance company heft (see Econ Weekly, Nov. 15th, 2021). Hartford-based companies include health insurers like Cigna and Aetna (the latter now owned by CVS) and property/casualty insurers like The Hartford, a company founded in 1810. Insurers with corporate headquarters elsewhere, like New York City-based Travelers, typically have large office footprints in Hartford. Together with manufacturing and state government (Hartford is Connecticut’s capital), insurance helped make central Connecticut an economic powerhouse through the first half of the 20th century. It doesn’t quite hold that status today, however. The fact is, jobs in all three sectors—insurance, manufacturing and government— have contracted since the start of the millennium, according to a 2019 HUD report. A 2003 New York Times article entitled “Hartford Is No Longer the Insurance Capital” proved hyperbolic. It still is. But due to mergers, divestitures and layoffs, the area’s financial sector (including insurance) saw employment drop from 70,000 in 2000 to 57,200 in 2019. Between 2007 and 2019, the overall metro economy grew a mere 5%. Population, meanwhile, shrank 1% during the 2010s. Connecticut, once a hotspot for companies fleeing urban centers like New York, more recently has a history of seeing companies flee for greener pastures. These include giants like UPS, which left for Atlanta in 1994, and GE, which left for Boston in 2016. Hartford itself lost many headquarters over the years, not to mention its only major league sports franchise—NHL’s Whalers left for North Carolina in 1997. More recently, the merger between Raytheon and Connecticut’s United Technologies saw HQ jobs move to the Boston area. The state, by the way, didn’t have a personal income tax until the early 1990s. The Hartford region also lost jobs in gun manufacturing, something it was known for in the early days of the industrial revolution. Connecticut’s capital, alas, has a legacy of problems familiar to most northeastern cities, including de-industrialization, suburbanization and discriminatory practices that left large racial gaps in wealth, income, home ownership and access to good schools. Unflatteringly, Hartford today looks more like Baltimore than Boston, a city with no shortage of wealthy suburbs but a deeply troubled inner core. The city of Hartford, according to Census data, has a poverty rate of nearly 30%, with more than a quarter of adults over 25 lacking even a high school degree. Among residents, 38% identify as Black; 44% also or separately identify as Hispanic. Hartford is also much smaller city than even Baltimore—the metro area ranks number 49 by population nationwide (Baltimore is 21). So it doesn’t have the tourism economy that even Baltimore has, let alone what New York and Boston can generate. A better comparison might be to Trenton, another northeastern state capital with strikingly similar demographic data (the poverty rate for one is almost identical). Hartford, furthermore, lacks the downtown amenities and housing that help attract knowledge workers—many prefer to live in places like New York and Boston. To be clear, Hartford has made progress in this area, investing in urban renewal projects. It’s also, like so many areas across America, getting a boost from the booming transportation and distribution sector. Sure enough, Amazon has a major presence in Hartford, conveniently located roughly halfway between Boston and New York, not to mention within an eight-hour drive of 30m Canadians. State and local government jobs help anchor the labor market, as do health care jobs. The local power provider Eversource is a big metro area employer. So is the University of Connecticut. Also notable is the sports channel ESPN, recent layoffs there notwithstanding. The region, long a magnet for migrants from Puerto Rico, continues to attract people from the island. Clearly, the dawning age of remote working is an opportunity, with all those hedge fund, university and defense contracting jobs within comfortable reach if only commuting there two or three days per week. Same for jobs in Providence, New York and Boston (though inconveniently, Hartford is not on Amtrak’s busy northeast corridor line). As MetroHartford Alliance likes to say, citing a 2019 C2ER study, living costs in Connecticut’s capital are 21% cheaper than in Boston, and 34% cheaper than in New York. Perhaps a good place to move after all… especially if you’re in the insurance business. (Sources: U.S. Census, MetroHartford Alliance, HUD, Bureau of Economic Analysis, Stamford Advocate, Hartford Courant).

Looking back

March 2020: A decade removed from an epic financial shock, the U.S. economy—in March of 2020—suddenly faced another one. This time, a respiratory disease was sweeping through the country, prompting public health officials to close large parts of the economy to protect lives and preserve hospital capacity. Companies and governments reacted with mass layoffs. Financial markets reacted with a “dash for cash,” even selling off U.S. Treasuries, which are supposed to be just as good as cash—the whole structure of the global economy in fact depends on this perception of equivalence. The Federal Reserve thus needed to react as well, which it did by buying large volumes of Treasuries (as well as closely related mortgage-backed securities); this shored up demand. It cut its federal funds rate target to essentially zero. It changed its forward guidance to reassure markets that rates wouldn’t go up until the job market significantly improved. It reactivated and expanded swap lines with foreign central banks, to make sure they had sufficient access to dollars. It lowered its discount rate for U.S. banks that needed dollars. For other U.S. and even foreign institutions, it provided dollars through overnight “repo” transactions. Not stopping there, the Fed established facilities to loan directly to companies, small businesses and municipal governments—much of this went beyond what it did even during the financial crisis. As chairman Jay Powell said in a March 15th press conference, it was helpful that the economy entered the new crisis on a “strong footing,” characterized by low unemployment, rising labor force participation and significant gains for lower-income workers. That said, the Fed actually enacted three quarter-point rate cuts in 2019, unnerved by weak business investment, manufacturing sluggishness, falling exports, tariff wars and an inverted Treasury yield curve (this meant longer duration bonds were offering lowering yields than shorter ones, often a harbinger of recession). The Fed decision to cut in 2019, furthermore, was supported by a decade of quiescent inflation. Sure enough, in March 2020, the bigger fear was deflation, as energy prices crashed and demand throughout the economy plummeted. Lo and behold, the Fed’s measures—plus the $2.2 trillion CARES Act passed by Congress and signed by President Trump—set the stage for a surge in demand that remains present at the start of 2022. These and subsequent stimulative measures, however—in tandem with the pandemic’s impact on labor markets and supply chains—brought inflation back with a vengeance in 2021 (see chart below):

Nails: That seems to be an odd topic for National Public Radio. But sure enough, the NPR’s Indicator podcast did a whole show on the evolution of nails—the kind used for construction—in the American economy. Economist Dan Sichel studied the humble nail, considering it a good proxy for how prices have changed over time, since the product itself hasn’t changed much (unlike say, a car, which is a very different product in 2022 than it was in 1922). Nails were important to building houses and other structures since the earliest days of the American economy. Between the 1880s and the 1920s, however, a shift from using iron to steel, new production designs and cheaper power all conspired to make nails a lot cheaper. That proved revolutionary for the construction industry, which could now use the balloon-frame method of building houses, involving use of two-by-four pieces of lumber nailed together. Doing so would previously have been too expensive because of all the nails that are required. According to Sichel, this shows how innovation changes the economy in unexpected ways; it’s not always about advances in computers and high technology. As it happens, productivity in construction has been woefully absent since World War II, which is one reason why the U.S. (and most developed economies) lack affordable housing. Nails, meanwhile, have become costly in recent years, due to tariffs, higher materials costs and higher shipping costs.

Looking ahead

Autonomous Trucking: How close is a world with driverless trucks for transporting cargo? Not close at all, says Phil Koopman of Carnegie Mellon University. As early as the mid 1990s, engineers were already capable of building cars that could drive across the country 98% hands-free. The problem is the last 2%, which is extremely difficult to solve. Why? Because, he says, “there’s an infinite variety of weird stuff in the world.” For that reason, he thinks complete replacement of truck drivers—there are nearly 2m of them in America—is a “long way into the future.” University of Pennsylvania sociologist Steve Viscelli, himself a former truck driver, agrees. In an interview on Lex Fridman’s podcast, he pointed out that truck drivers do more than just drive, handling deliveries, for example. He also explained that autonomous driving on open highways is not always easier than elsewhere, as is commonly believed. The reason is that trucks move at high speeds on highways, making it difficult to quickly brake when necessary. Google’s Waymo, as it happens, is already running autonomous taxis in Arizona, in relatively benign conditions (i.e., no snow to worry about).

Autonomous Trucking: Operating heavy tractor-trailer trucks autonomously indeed appears challenging. But plenty of companies and researchers are working to make it a reality. One reason is the market’s potential—trucking is a $700b-a-year industry. The trucking firm J.B Hunt last week announced a partnership with Waymo’s Via unit, “with ultimate plans to complete fully autonomous transport in Texas in the next few years.” Viscelli has suggested that autonomous trucking might start with overnight deliveries, when traffic is light, or in a convoy arrangement with a lead truck operated by a human driver.

ALSO VISIT www.econweekly.biz. Individual subscriptions available for just $15 per month. Company and University licenses also available.

Interested in helping develop and market Econ Weekly? I’d love to hear from you. Email me at jay@econweekly.biz. And be sure to sign up for my free newsletter about the North American railroad industry: