Geopolitical Threats Escalate... What's the Fed to Do?

PLUS: This Week's Featured Place: Chicago, Illinois

Issue 57: February 28, 2022

Inside this Issue:

Putin or Powell: Either’s Action Could Cause Contraction

Crude Subdued: For Now, Oil (WTI) Holding Below the $100 Mark

Salvation from Inflation? Ultimately, Will Pricey Oil Foil Pricing Pressure?

Or if Oil’s No Foil: Does the Fed Need Pricey Loans to Break Inflation’s Bones?

Early Signs of February Vigor: But Threats from Housing Getting Bigger

Warren’s Whales: Berkshire Hathaway’s Giant Four

Bleed the Fifth: Health Care Hit Nearly 20% of GDP in 2020

Fourth Quarter Pounder: Another Strong Result for Ronald McDonald

And This Week’s Featured Place: Chicago, Illinois, Windy Wonderland

Quote of the Week

“The median U.S. home value has increased 25% over the last two years… today, American homeowners are sitting on record levels of home equity.”

- Rocket Companies CFO Julie Booth (Note: Rocket is the number one home mortgage lender in America)

Market QuickLook

The Latest

Not this week. Not next week. But one week thereafter, at its two-day meeting that starts March 15th, the Fed will make its big decision. Unfortunately, that decision just got a lot more complicated by events 5,000 miles from Washington.

Jay Powell and his colleagues have by now concluded that it’s time to lift the price of money, in order to drop the price of everything else. Or put another way, to take some wind out of the economy’s sails, in order to slow the advance of inflation. The advance of Russia’s army into Ukraine, however, threatens to make inflation worse by lifting the price of commodities, most importantly oil. Does this call for a more aggressive rate increase, perhaps by a half point? Or even a full point?

Or maybe the opposite makes more sense. Higher oil prices might do the Fed’s job itself, curtailing demand in the same way higher borrowing costs would. Does the Fed want a double dose of demand depressants? Maybe Putin, not Powell, proves the ultimate inflation slayer. Should the Fed do a smaller rate hike, or perhaps leave rates where they are? Of course, who knows exactly how the economy will respond to $100 oil, which by the way is less expensive in real terms than the $100 oil of the early 2010s (let alone the $130 oil of mid-2008)? Besides, who knows where oil prices will go from here? And if they do stay high, who knows how much demand destruction will follow, and how long it would take before reaching the Fed’s goal of bringing down consumer prices?

Oil prices, to be clear, largely ended the week where they started, at around $92 a barrel (that’s WTI; Brent prices are running a bit higher). The S&P 500 stock index actually gained a bit when all was said and done. Treasury bonds were calm. Even the inflation threat looked a bit less menacing, based on the latest Commerce Department report on personal income. Its measure of personal consumption expenditure (the PCE index) showed a 6.1% y/y increase for January, unnervingly high for sure but not quite as bad as the Labor Department’s inflation estimate (the CPI index) of 7.5%. The Fed, keep in mind, pays more attention to PCE.

Last week’s income report did show further gains in consumer spending during January, relative to December, even as Americans saw their inflation-adjusted incomes decline. This week, we’ll learn more about trends in February with publication of the Labor Department’s latest jobs report. January’s report, remember, was surprisingly strong.

There’s already some evidence that February has been a strong month for the economy. The IHS Markit Purchasing Managers Index suggested “considerable momentum” in private sector output as Covid labor disruptions faded, health restrictions were relaxed, supply chain bottlenecks eased slightly and companies successfully raised prices to offset cost inflation. Output gains were especially strong in the service sector, though manufacturers produced more as well. In the IHS report’s own words: “The pace of economic growth accelerated sharply in February as virus containment measures, tightened to fight the Omicron wave, were scaled back. Demand was reported to have revived and supply constraints, both in terms of component availability and staff shortages, moderated.”

Sounds bullish, no? Maybe the Fed should raise rates aggressively. But wait, is there something brewing in the housing market? It’s a critical barometer of the country’s economic health. Major companies in the sector, including the mortgage lender Rocket last week, remain upbeat—Rocket continues to see a “robust mortgage market” despite rates that are already rising in advance of the Fed’s big decision. However, the National Association of Realtors published a report last week showing pending home sales—considered a leading indicator of housing activity—slipped nearly 6% from December to January.

That shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise. U.S. home prices rose 18% y/y in the final quarter of 2021, according to new data from the Federal Housing Finance Agency. Now that lending rates for mortgages are up as well, is it any wonder the housing market appears—finally—to be cooling off? By the way, U.S. housing prices have increased for ten straight years now. Is that a good thing? Well, yes for existing homeowners. Not so much for families looking to buy. A few more facts from the new FHFA data: The steepest Q4 housing price gains were in Arizona, Utah, Idaho, Florida and Tennessee. The smallest gains were in the District of Columbia, Louisiana, North Dakota, Maryland and Alaska. Boise, an all-star housing market throughout the pandemic, saw prices slip from Q3 to Q4. Interestingly, prices in even some of the most economically-depressed metros in the country—Camden, New Jersey, and Gary, Indiana, for example—are up by double digits.

A few other updates from around the economy last week: Home Depot reminded everyone just how remarkably well it did during the pandemic, growing revenues more than $40b in just two years—it previously took nine years to grow that much. Home Depot’s rival Lowe’s, also seeing ongoing demand resilience, cited the advantages of scale when dealing with current supply chain bottlenecks (both retailers are among the country’s largest importers of freight containers). Booking, the online travel site, sees strong demand for travel this summer. Werner, a logistics firm, said trucks and trailers are more difficult to get right now than even drivers. Occidental Petroleum, relishing oil’s price spike, said 2021 was its strongest year in three decades. But, it added, “we have no need and no intent to invest in production growth this year.” (that’s not what American consumers and transportation companies want to hear). The National Association of Business Economists held a webinar on 5G telecom and its potential to greatly improve manufacturing productivity (think robots communicating wirelessly across factory floors). The Commerce Department, meanwhile, revised its Q4 real GDP growth estimate to 7% (that’s a quarter-to-quarter figure, annualized).

The biggest earnings release this past week? Berkshire Hathaway’s annual report, accompanied as always by Warren Buffett’s letter to shareholders. He spoke of the company’s “four giants,” namely its insurance business (which includes Geico), Apple (it’s the tech company’s top shareholder with a 6% share), BNSF (America’s largest railroad) and BHE (a “utility powerhouse”). Besides Apple, Berkshire also owns substantial non-controlling stakes in (among other firms) American Express, Bank of America, Moody’s, China’s BYD, Japan’s Mitsubishi, Kraft-Heinz, Coca-Cola, General Motors, Chevron, Verizon and Occidental Petroleum (referenced above).

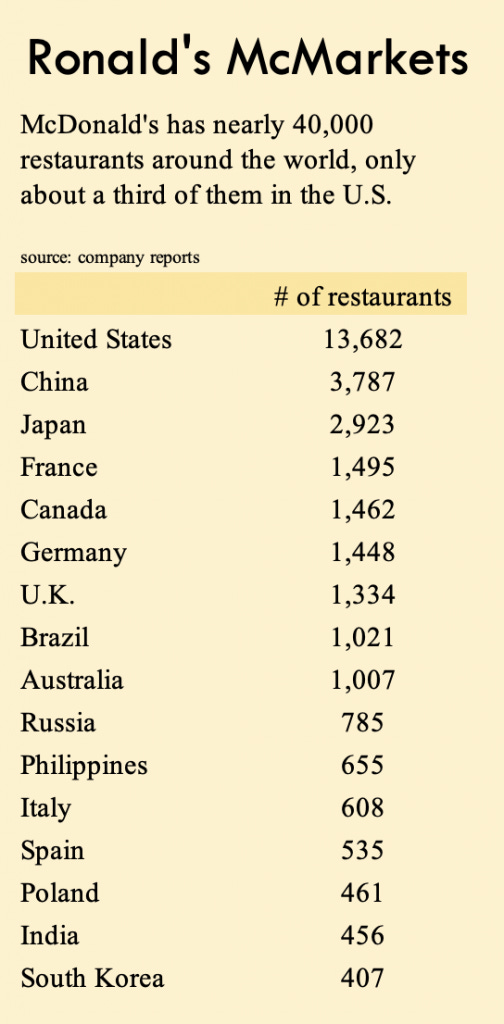

Besides the February jobs report coming this Friday, this week will feature a Congressional appearance by Jay Powell and a meeting by the oil cartel OPEC, also attended by non-member Russia. And just a few more words about Russia and its relevance to the U.S. economy. Trade between the two nations is tiny. But Russia’s large output of not just energy but wheat, aluminum, palladium, titanium, etc. influences global commodity prices. Russia of course depends on cash from selling its commodities, no less than the world depends on acquiring them. So far, the U.S. and Europe have largely exempted energy sales at least, from their sanctions. Russia, furthermore, is a decent-sized consumer market for companies like Apple, Procter & Gamble, PepsiCo and McDonald’s (which has nearly 800 restaurants there). Boeing sells planes to its airlines and maintains a Russia-based engineering team. As Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics points out, Russia and Ukraine together produce about half of the world’s neon used in semiconductors.

The point is, the Russia-Ukraine conflict, while not posing much of a direct impact to the American economy, does pose additional risks to not just commodity inflation but also global supply chains (the last thing the world needs right now). Another indirect risk is spreading geopolitical instability, especially if supplies of Ukrainian and Russian wheat and corn are disrupted. As history will attest, from France in 1789 to Egypt in 2011, the rising price of bread is a notorious instigator of revolutions. Let’s hope for peace and calm.

Companies

McDonald’s: In 2019, The Economist wrote: “Every day, McDonald’s serves 69m customers, more than the population of Britain or France.” Is there anyone on the planet that doesn’t recognize the Golden Arches? Last year, McDonald’s generated $23b in revenue. More importantly, it retained nearly $8b of that $23b as net profit. To be clear, the world’s humans consume a lot more than $23b worth of Big Macs, Happy Meals, Chicken McNuggets and the like. It was more like $100b worth. But much of that revenue goes to franchisees, independent businesses (the majority of them abroad) that essentially pay McDonald’s a fee to use its brand and IT systems. More than 90% of McDonald’s restaurants are operated by franchisees, who control all matters related to employment, marketing and pricing. The company itself employs about 200,000 people, including those at the modest number of restaurants it self-operates. But counting the franchised locations, more than 2m people work for the brand, from Argentina to the Virgin Islands (in case you’re wondering, there are nearly 800 McDonald’s locations in Russia, and 108 in Ukraine). Even during the worst moments of the pandemic in 2020, the Chicago-based company stayed solidly profitable, never mind that revenues during 2020 dropped by 10%. Critical to its resilience were what management calls the “3 Ds,” namely digital, drive-thru and delivery. Currently, about a quarter of all sales come through digital channels (mainly its mobile app), with the figure more like half in China, France, the U.K. and other key overseas markets. McDonald’s is one of the world’s top corporate advertisers, spending $4b a year on marketing. With the pandemic now easing, and more people once again commuting to work, breakfast revenues are rising. Its high-margin McCafe product happens to be the number two coffee brand in the world by servings, behind only Starbucks. A key goal now is building “chicken credibility” to match the success of Chick-Fil-A, most importantly. Home delivery options are expanding, though this is less profitable than in-store sales. A loyalty plan helps it obtain useful data on consumer preferences. It’s now testing plant-based meats as a menu item. McDonald’s, however, is feeling the nationwide labor shortage, along with the nationwide bout with inflation. It also has a more unique aggravation: Criticism about animal cruelty from longtime activist shareholder Carl Icahn. One final stat to take away with your order: In top markets anyway, three quarters of the population live within three miles of a McDonald’s.

Tweet of the Week

Sectors

Health Care: The U.S. economy has its immediate problems, i.e., inflation. And it has its structural problems, i.e., a dysfunctional health care system that cost the country $4.1 trillion in 2020. That was 19.7% of GDP, up from 17.6% in 2019. One Medical, a health care provider, recently showed the results of a survey in which 81% of Americans expressed dissatisfaction with their health care experience. Patients, a separate data point showed, waited 29 days on average to see a doctor. Employers, meanwhile, now pay more than $21,000 on average to provide family insurance coverage for their employees. In 2020, 31% of all health spending was for hospital care, 20% for doctors and clinics, 8% for retail prescription drugs, 5% for care in nontraditional settings like schools and offices, 5% for nursing home care, 3% for dental services, 3% for home health care and so on. That data is from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid.

Markets

Interest Rates: As the Fed prepares to raise interest rates in March, expect a tightening of the money supply, right? Well, the story is more complicated. The Fed can influence rates simply by paying whatever amount of interest it chooses to participants in the giant overnight lending market (which is crucial for settling payments between different institutions). More specifically, it sets two different overnight rates: 1) the interest it pays on reserves banks keep with the Fed and 2) the interest it pays to institutions that aren’t members of the Fed system, who conduct overnight reverse repurchase agreements. But here’s the question: How much will any short-term rate changes ripple their way up to longer-term borrowing?

Based on Treasury rates of different durations, long-term rates have in fact been pretty flat since the beginning of the year. Is that because the Fed itself has been buying so many longterm bonds, pushing their prices up and yields down? Or does it signal what Milton Friedman called the interest rate fallacy: that perhaps when longterm rates are low, it’s a sign of excessively tight Credit might be cheap, as the Maroon Macro newsletter points out, suggesting loose money. But cheap doesn’t mean abundant, and it might that only the biggest and most credit-worthy borrowers are getting access to cheap credit. Indeed, according to some economists, the world is still suffering a shortage of money due to a shortage of longterm credit. Since the global financial crisis more than a decade ago, many global entities have been unwilling to lend much, other than to ultra-safe borrowers like the U.S. government (thus holding down Treasury yields). Jeff Snider of Alhambra investments is one vocal proponent of this idea, stressing the negligible impact of Fed policy given the immensity of the dollar funding market outside of the U.S. (called the Eurodollar market). A key point to remember is that the vast majority of global money is created through lending, a.k.a. credit. And a lot of it happens abroad. Someone less partial to this theory might say: How could money possibly tight if even pandemic-thrashed companies like cruise operators were able to easily and cheaply borrow from the private sector throughout the pandemic? Unlike airlines, cruises did not receive credit assistance from Uncle Sam.

Labor: Here’s another example of where the U.S. labor market isn’t producing sufficient supply relative to demand. The Atlantic looks at America’s doctor shortage, which will likely get worse regardless of what happens with Covid. The Census, it notes, projects that in 12 years, there will be more senior citizens than children in America for the first time in history. And that alone implies the need “for more doctors to be part of America’s health-care system.” Another issue is employee burnout among family primary care physicians.

Labor: A new release by the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that in 2021, there were 16 major work stoppages, defined as those involving more than 1,000 workers and lasting at least one weekday work shift. The lowest number on record was nine in 2009. The most was 470 in 1952. In 2021, the sector most affected was education and health. Among manufacturers, John Deere and Kellogg’s were two prominent companies hit by strikes last year. A current labor dispute familiar to many Americans is Major League Baseball’s lockout of players, postponing the start of Spring Training. It also, parenthetically, postpones the start of what will surely be another despondent season for the New York Mets.

Government

Medicare: A recent article by American Prospect looks at the Medicare, a federal program established in 1965, primarily for Americans over 65 (Medicaid is something separate, catering to the poor). Medicare is not, the Prospect article explains, a public health care system like what the Defense and Veterans Affairs departments provide (i.e., Tricare and the Veterans Health Administration, respectively). Medicare is instead public financing that relies on a joint public-private insurance arrangement. The rules are set by the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and Congress, and all claims are processed by insurance companies under contract to the federal government. All beneficiaries/patients, as the Congressional Research Service (CRS) explains, are entitled to the same coverage regardless of income or medical history. The program is giant, covering about one in six Americans (virtually everybody over 65).

Medicare, CRS further explains, consists of four distinct parts. Medicare Part A (hospital insurance), B (for doctor visits, lab work, etc. but not vision, dental, hearing or longterm care), D (prescription drugs) and C (called Medicare Advantage, or MA), which are private plans people can take in lieu of Parts A and B. As of 2020, about one-third of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in MA.

CMS said total Medicare spending in 2020 was $830b, or about a fifth of all the money Americans spent on health care (yes, that total is more than $4 trillion). The Congressional Budget Office, meanwhile, said in 2019 that by 2030, Medicare spending is expected to have almost doubled due mainly to growing enrollment and increasing health care costs. Some joke that the U.S. Federal government, based on the health, pension and military spending that dominates its budget, has basically become an insurance company with a standing army.

Where does Medicare get its money? Through two separate trust funds. One is for Part A (the hospital part), which gets most of its funds from a payroll tax incurred by employers and their employees. (This fund is on pace to be insolvent in just a few years). The other Parts, however, get their money from general tax revenue, as well as the premiums users pay. States help finance some spending for Part D (the drug benefits).

Back now to the American Prospect article, which heavily criticizes the Medicare Advantage program. Originally conceived as a cheaper and alternative to Medicare, it’s now a “behemoth that has not saved one cent nor produced better outcomes.” To clarify, Medicare pays private insurance companies like Humana and United, which by themselves own about half of the 3,834 Advantage plans on offer. The companies take responsibility for administering the insurance, including the decisions about how much to pay doctors, and whether a patient’s claim qualifies for reimbursement. “The MA profit-making formula is simple,” the article says, “get a large sum of money from the Feds, spend less than traditional Medicare, give some of the excess to beneficiaries, and pocket the difference.” It adds: “Over the last 12 years (2009–2021), Medicare paid the MA plans $140b more than would have been spent if the same people stayed in Medicare.”

The article also discusses the practice of “upcoding,” whereby insurance companies record everything conceivably wrong about the health of a patient, leading to a higher risk score. The higher the risk score, the more the insurance firm can bill Medicare.

All of this is lucrative enough “to lure hedge funds and venture capitalists to invest in data mining companies and care aggregators, which are developing new ways to maximize MA’s profitable deals.”

A newer “Direct Contracting” model is now being trialed. According to Bloomberg Law, “the professional and global direct contracting model was designed to help move traditional Medicare away from fee-for-service care and toward value-based care, in which provider reimbursements are based on patient outcomes and cost efficiency.” Put another way, it “brings physician groups and team-based care to fee-for-service Medicare.” Or as the website ElderLaw Answers describes: “Direct Contracting [inserts] middlemen—Direct Contracting Entities (DCEs)—between traditional Medicare beneficiaries and their medical-care providers. Like Medicare Advantage plans, DCEs—most of which are investor-owned with ties to commercial insurers—would receive a monthly payment for a specific group of patients.”

Major DCEs include companies like 1Life, Clover and Oak Street, which are joining much of the health care industry in lobbying in favor of the idea (launched during the Trump Administration). Progressives in Congress are trying to kill it, calling it another threat to traditional Medicare. What will the Biden Administration do?

Places

Chicago, Illinois: It’s windy. Its shoulders are big. Its baseball teams are notoriously bad. We’re talking, of course, about Chicago, America’s third largest metro area behind New York and Los Angeles. It didn’t even exist as a town until the 1830s, some 50 years after the U.S. won its independence from Britain. By early 19th century, however, it was already recognized for its strategic location along Lake Michigan. Farmers would travel to Chicago, where their products could move cheaply via the Great Lakes, the Erie Canal and the Atlantic Ocean, reaching their two largest markets of the time: the U.S. northeast and Europe. Before the days of the railroad, shipping by water was much faster and cheaper than shipping by land. But the railroads would soon come, making the Erie Canal obsolete. Not Chicago though. Far from losing its relevance, the city became the epicenter of the nation’s railway system, a status it retains even today. Economically, no city benefitted more from the Civil War than Chicago. It was by then (the early 1860s) the dominant seller of grain, meat and lumber, all bought in mass quantities by the U.S. army. According to William Cronon in his book “Nature’s Metropolis,” half of Chicago’s 110,000 people in 1860 were immigrants, mostly from Ireland, Germany and Scandinavia. That helped make it America’s eighth largest city at the time, up from 17th in the 1850 Census. Chicago continued to boom during the flourishing of America’s post-Civil War industrial age, becoming a manufacturing powerhouse. From 1900 to 1950, it stood behind only New York in population, earning it the nickname “America’s Second City.” Railroads had lost some of their relevance in the age of automobiles. But Chicago would become a premier center for trucking too. It also gave birth to the great retail empires of the consumer age, most famously Sears but also Marshall Field and Montgomery Ward. It simultaneously retained its manufacturing clout, producing farm equipment, food, railroad cars, steel and lots more. Immigrants continued to come, from Poland, Italy, Russia and so on. Importantly, the Great Migration north brought large numbers of African Americans to Chicago, often filling factory jobs, including wartime production roles during both World Wars. The city’s industrial shine, unfortunately, started wearing off in the second half of the 1900s. As the U.S. suburbanized and de-industrialized, the city of Chicago—like many large cities at the time—experienced urban decay, an outflow of affluent whites, racial tensions, crime, municipal corruption, failing public schools and substandard housing. Robert Spinney’s book “City of Big Shoulders” recounts the time in 1955 when Soviet officials visited Chicago’s Henry Horner housing project, remarking afterward: “We would be thrown off our jobs in Moscow if we left unfinished walls like this.” Washington didn’t disagree, issuing a 1968 federal report that described Chicago’s public housing projects as “remindful of gigantic filing cabinets with separate cubicles for each human household.” Many surrounding suburbs, to be sure, thrived in the decades leading up to the new millennium. It’s where many of Chicagoland’s most iconic companies were headquartered, including McDonalds (Oak Brook) and United Airlines (Elk Grove). The downtown Loop, meanwhile, did retain a core of influential companies like Sears, housed in what was once the world’s tallest building. The city, furthermore, during the first Mayor Daley administration, didn’t experience quite the fiscal collapse that New York suffered in the 1970s. Nevertheless, as Spinney writes, the city lost 60% of its manufacturing jobs—60%!—between 1960 and 1995. Between 1973 and 1977 alone, total job losses amounted to 123,000. Another 83,000 disappeared in the early 1990s, a dark period for U.S. cities that coincided with surging crime rates. In the new millennium, would Chicago follow the troubled path of its neighboring industrial colossus Detroit, unable to recover from all those lost manufacturing jobs? Or would it follow the inspirational path of New York City, which successfully transitioned to a knowledge-based economy? Happily, Chicago would indeed join New York as an all-star global city, powered by a diverse set of industries. Chicago remains vital to airlines, railroads and trucking firms. It also remains home to many food producers. Tourism, including international arrivals and business conventions, has been a major driver of Chicago’s renaissance. Like everywhere else in the 2000s, Chicago added jobs in health care and education. The University of Chicago has perhaps the most famous economics department of any school worldwide. Governments—federal, state, county and local—are top employers. The city is also home to some of the world’s top consulting, accounting and legal firms, enticed by all the nonstop worldwide air service available from O’Hare airport—for one thing, you can get out and back to New York, Texas or California in a day. According to HUD, the population of Chicago’s Loop doubled in the first 15 years of the 2000s. Boeing moved its headquarters from Seattle. United replaced Sears in what’s now called the Willis Tower. McDonald’s came to downtown as well. JPMorgan established a big Chicago presence when it merged with Jamie Dimon’s Bank One in 2004. The next year, the White Sox baseball team actually won a World Series—their first in almost 90 years. Even more improbably, the Cubs won eleven years later, for the first time since the Roosevelt Administration—TEDDY Roosevelt. Chicago further gained worldwide notoriety when longtime resident Barack Obama became president in 2008. It’s hard to think of anyone more globally famous than the Obamas, except perhaps Michael Jordan and Oprah Winfrey, two other Chicago figures. Michael Jackson, incidentally, is from Gary, Indiana, close enough to be a Chicago suburb. Bill Murray, Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder… should we mention Kanye West? Ronald Regan, by the way, is still the only president that was born in Illinois, though Hillary Clinton came close. (Reagan was born about two hours west of Chicago; Abraham Lincoln lived in the capital Springfield three hours southwest).

Chicago naturally grappled with familiar big city problems even during the boom of the past twenty years. The question now is how much permanent damage the pandemic will do. In the half-decade leading up to 2020, Chicago was creating nearly 11,000 jobs a year in leisure and hospitality, many catering to visitors from abroad. They all disappeared when Covid arrived, and it’s unclear how many will ultimately return. The city is seeing rising levels of crime again, and the work-from-home phenomenon is depressing downtown activity and transit usage. Chicagoland as a whole, meanwhile, was alone among America’s top 20 metros to have lost population in the 2010s. Even its old rival St. Louis grew by half a percentage point. The Cubs, we should add, are back to being bad—they lost 91 games last year. The city itself grew a bit, however, thanks again to immigration, this time primarily from Latin America and Asia. According to the Chicago Sun-Times, Latinos now account for roughly 30% of the city’s population, surpassing the Black population. Blacks have in fact been leaving the city in large numbers, many moving to booming Sun Belt metros like Dallas and Houston. Economic development officials, meanwhile, are touting Chicago’s progressive social values (you can feel the rivalry with Texas by watching this:

).

One thing Chicago doesn’t have: Good weather. That didn’t matter when it was the best place in America for farmers to move produce, or the best place through which to run a railroad. It’s still the best place to do many things, including, apparently, running giant companies like Boeing, United Airlines, McDonald’s, Walgreens, Archer Daniels Midland, Allstate, Caterpillar and Abbot Labs. All feel Chicago is a good place to attract talent. But for growing a population, especially in a time of dwindling immigration, being a windy city doesn’t help. All else equal, most people want sunshine and warmth.

Some new Labor Department data on Cook County, which covers the city of Chicago: In September, total employment grew 3% y/y. But leisure and hospitality employment grew 23%, bouncing back from depressed levels. Financial jobs shrank 2%. Manufacturing shrank yet again, this time 1%. Chicago’s largest sector for jobs—professional services—rose 4%. Almost as large is the trade and transportation sector, where jobs grew 1%. Similar story for the similarly-sized education and health sector, where employment rose 2%. Wages grew most, meanwhile, for IT jobs. (Sources: Census, World Business Chicago, Chicago Sun Times, Public Housing in Chicago by Charlie Rubin, “Nature’s Metropolis” by William Cronon, “City of Big Shoulders” by Robert Spinney).

Abroad:

Russia: According to OEC.world, Russia exported $407b worth of goods and services in 2019, far exceeding its $238b worth of imports. The reason for its trade surplus, of course, is oil and gas, which (including refined products) accounted for 53% of that $407b figure. Raw materials like aluminum, gold, diamonds, copper, nickel, platinum, wood and fertilizer account for another big chunk of its exports. Wheat accounts for 2% of the $407b (it’s actually the world’s biggest exporter of wheat). The top destination for its exports? China, followed by the Netherlands, Belarus and Germany. Only 4% of Russia’s exports go to the U.S.

Russia: China is Russia’s top source of imports as well. It buys a lot from Germany too. What does Russia buy from abroad? Automobiles, most importantly, along with pharmaceuticals, cell phones, computers, clothing, etc. Just 4% of its imports (the same percentage as its exports) come from the U.S. Taking a broader view, Russia’s GDP, at about $1.5 trillion, is smaller than that of Italy. It’s also a country that faces a severe case of shrinking and aging demographics.

Ukraine’s top two exports, in case you’re wondering, are corn, wheat and iron ore. It’s an energy importer unlike Russia.

Looking Back

Social Networks: Thomas Dyja’s book on the last four decades of New York City— “New York, New York, New York”—contains an interesting discussion on the economic importance of social networks, long before there was any such thing as social media. “New Deal laws that kept banking safe and dull,” he writes, had also “kept strivers out.” When these laws were eroded in the 1980s and 1990s, it opened the door to “hungrier, smarter people from the other side of the tracks.” In 1982, incidentally, New York City for the first time employed more people in the FIRE sector—finance, insurance and real estate—than in manufacturing. But who was getting these new well-paid FIRE jobs? The value of one’s social network was a big determining factor. “Where you worked mattered more than what you did. Where you went to school mattered more than what you learned.” Why? Because of the social ties one could foster. “Through connections come useful information, job tips, stock tips, heads up on an apartment… a cute guy your sorority sister can hook you up with.” Amassed together, this created a mountain of social capital essential to entering and thriving in New York’s revived economy. Those outside these networks, however, had many fewer opportunities to benefit, leaving the city’s poverty rate (and racial divisions) stubbornly unchanged even amid its growing wealth.

Looking Ahead

Cryptoeconomy: Coinbase, FTX, Crypto.com and eToro—all of them online platforms for trading crypto assets—spent big bucks to advertise during the Super Bowl. Is it another symbol of crypto going mainstream? Or a symbol of overexuberance akin to certain Dot.Com Super Bowl advertisers two decades ago (remember the Pets.com spot from 2000)? Coinbase, for its part, naturally sounded bullish in its earnings call last week, pointing to all the capital and talent still pouring into crypto ventures. The breadth and quantity of crypto-based internet applications continues to grow beyond just trading assets, it said, citing decentralized finance, NFTs, gaming and social media apps, decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) and digital identity systems. One in four U.S. households, say some researchers, now own a cryptoasset. Currently, Bloomberg reports, the “hottest spot in crypto” is stablecoins, the largest of which (i.e., Tether) are pegged to the U.S. dollar. Traders in the crypto space, it seems, are moving their money to what’s effectively an equivalent of cash. What would happen if everyone simultaneously tried to redeem their stablecoins for actual dollars? Could platforms like Coinbase handle that? Might such a run on stablecoins prove de-stabilizing to the financial system? It’s a concern expressed by the Fed and other regulators.

Cryptoeconomy: Former Coinbase president Asiff Hirji recently presented at the Princeton Bendheim Center for Finance, talking about the future impact of blockchain technology on financial services. Clearly, he argues, new crypto applications will allow for bilateral, real-time transactions. By enabling an open public registry of all transactions, the need for third-party verifying intermediaries (i.e., banks) goes away. While inventing Bitcoin, Hirji says, Satoshi Nakamoto (whoever that is) solved one of the hardest problems in all of computer science. Now data can be verified online using a mix of cryptography and consensus mechanisms involving thousands of computers around the world. Hirji said decentralized, crypto-based finance is still in its early stages, mostly centered on people buying and selling crypto assets (see above). Ultimately, however, people will buy and sell real-world assets—stocks, bonds, real estate and so on—using blockchain technology. But will it be truly decentralized? Or will third parties like Coinbase still have a role, ensuring security and regulatory compliance but perhaps sacrificing some security and privacy? Hirji, who now runs a blockchain-based financial services firm called Figure, says the public will have to decide.

Hirji, by the way, used to run Ameritrade, a major trading platform for traditional securities and other assets, now owned by Charles Schwab. While there, he said, company data showed unambiguously that the people who traded the most, lost the most money. Sorry, day traders.

State of the States

State job markets, ranked by percentage of civilian workers employed in each sector

source: Bureau of Labor Statistics