Econ Weekly (Sep. 27, 2021)

Featured Place: Franklin County, NY

Inside this Issue:

Debt Ceiling Squealing: Will Congress Really Risk a Treasury Market Collapse?

Shifting Dates on Rates: Fed Sees Earlier Lifts as Inflation Persists

And Another Policy Peril: A Government Shutdown Looms

Evergrande Grind: Will a Chinese Sneeze Cause Global Unease?

No Staff, No Stuff: More Companies Share their Supply-Side Frustrations

Tales of Missing Males: Why Are So Many American Men Not Working?

Repeal that Deal: DOJ Sues to Stop an Airline Alliance

Quantitative Freezing: Has the Fed’s QE Strategy Actually Hurt the Economy?

Loopthink: The Latest in Hyperloop Transport

Digital Dollars: The Merits of a Central Bank Digital Currency

And This Week’s Featured Place: Franklin County, NY, A New York State of Grind

Quote of the Week

“Given the supply chain challenges, the industry will not be able to quickly remedy the supply shortage with increased production. Accordingly, we expect the market to remain in its current balance or should I say, imbalance for an extended period of time.

- Lennar executive chairman Stuart Miller

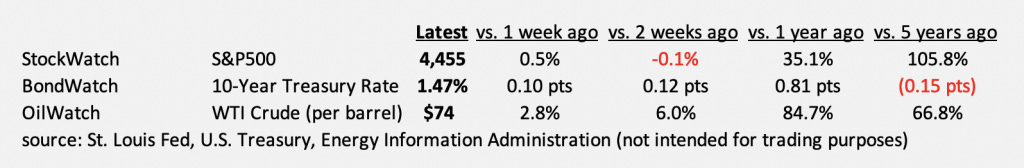

Market QuickLook

The Latest

In Washington, there’s so much happening. But nothing’s happened yet.

The Federal Reserve made no major policy moves at its meeting last week. But it made clear that a drawdown of its bond buying is near. Board members separately telegraphed a more imminent hike to interest rates, concerned about supply-chain driven inflation that’s proving stickier than anticipated. On Capitol Hill, still no resolution to the debt ceiling debate, upon which rests a crucial foundation of the global economy, i.e., the market for Treasury debt. Still no passage of the infrastructure bill either. Or the more controversial (and more expensive) care economy bill. Oh, and another government shutdown looms.

Elsewhere in the halls of federal power, the Justice Department again signaled its intention to pursue stricter enforcement of competition laws. It joined several states in suing to stop American Airlines and JetBlue from forming what the litigants are calling a “de facto merger.” DOJ separately settled a fraud case against China’s Huawei, relieving one of many sticking points in the ever-souring relationship between the world’s two largest economies.

Speaking of China, its debt woes have become a central concern for world markets, specifically the debts of its pervasive real estate sector. Everyone seems to be asking: Is China on the verge of a Lehman moment? That refers of course to the 2008 collapse of Wall Street’s Lehman Brothers, a trigger for what became the global financial crisis. Just as Washington had to decide whether to bail Lehman out (it decided not to), Beijing must decide whether the property developer Evergrande should get a bailout. After the Fed meeting last week, chairman Powell downplayed the U.S. financial sector’s exposure to China. But make no mistake: Many of America’s largest and most valuable companies, including Walmart and Apple, depend greatly on Chinese supply. The U.S. aerospace and agricultural sectors, meanwhile, are no less dependent on Chinese demand. Put another way, even as U.S.-China geopolitical hostilities intensify, U.S.-China economic co-dependence remains.

This discussion ties into the broader topic—a hot one right now—of whether economic globalization is unwinding. The Economist, analyzing U.S. companies, notes that two in five Russell 3000 firms make more than half of their sales abroad—it gave Netflix as one example. Interestingly, President Biden hasn’t undone any of the import tariffs imposed by his predecessor. The pandemic, all the while, brought a new emphasis on supply chain resiliency, even at the expense of supply chain efficiency. Does that foreshadow less outsourcing abroad? Or are the benefits of globalized production simply too compelling to abandon? Would American consumers tolerate the higher prices resulting from a less globalized economy?

The topic will likely get some attention as Q3 earnings season unfolds. The festivities begin in just a few weeks now, though several big companies reported their latest results last week. Nike, for one, joined the rest of Corporate America in lamenting the challenges of simply moving its products. FedEx, which moves products for a living, joined others in lamenting an inability to find enough workers. The homebuilder Lennar for its part, is a major actor in the housing shortage drama playing out across the country. Their laments, however, are tempered; most firms are still earning handsome profits as inventory shortages and robust demand drive up prices. That said, input costs do seem to be outracing price hikes, implying that Q2’s record corporate profits are now declining. There are of course some sectors that can only dream about record profits in the Covid era. Think airlines and restaurants, both hit hard again by the Delta variant, after a promising comeback this summer.

In the energy sector, ConocoPhillips agreed to buy Texas oil assets from Shell. US Bancorp, the fifth largest U.S. bank, agreed to buy a smaller rival. Amazon reportedly plans to open department stores, affirming the trend of omnichannel retailing even as e-commerce grows. Carnival, reporting results for June, July and August, ended the period with 35% of its cruise ships back in service, with full restoration targeted for next spring. Costco, one of America’s largest retailers, continues to report strong double-digit sales gains.

Stock markets gained too, despite worries about Covid, China, the debt ceiling, the removal of Fed stimulus and the persistence of supply-chain driven inflation. Treasury rates increased, reaching their highest levels since July. They’re still extremely low to be sure, underpinning a world of cheap and abundant capital. Is that about to change as the Fed begins to tighten?

This week, all eyes are on Congress. Absent the necessary legislation, the federal government shuts down on Friday.

The Fed Meeting

Eight times a year—that’s every six-and-a-half weeks—the Federal Reserve’s policymakers meet to make decisions that influence the cost and availability of money and credit. What did this Federal Open Market Committee, or FOMC, do at its latest meeting held last week? Not much, in terms of real action. No changes to interest rates. No changes to its pandemic-era policy of buying $120b per month worth of bonds ($80b in Treasuries and $40b in mortgage-backed securities from agencies like Fannie Mae).

Sounds like a sleepy meeting. Well, not exactly. The Fed did make some news, however anticipated, that it plans to start gradually reducing those monthly security buys as early as its next meeting in November. And the buying could stop completely by mid-next year. Mercifully, the market didn’t throw any tantrums in response, as it did after the Fed announced a plan to unwind a similar policy in 2013. Chairman Jerome Powell did say he’d like to see a solid September jobs report (if not necessarily a “knockout” report) before starting the process. The August report, remember, was rather weak as the Covid Delta resurgence all but froze hiring in the large leisure and hospitality sector.

When it comes to raising interest rates, there’s a much higher bar. “Liftoff,” as the Fed calls it, won’t happen until committee members feel labor market conditions are consistent with maximum employment, and inflation is at 2% or moderately higher (it’s currently much higher). There’s progress on both fronts, but it’s not there yet. About half of the FOMC members anticipate a rate hike next year. The other half sees one coming in 2023. Beyond that, the Fed will have to start thinking about shrinking its balance sheet, which grew enormously in response to the 2008-09 housing crisis, and even more in response to the Covid crisis.

Powell, in a press conference after the two-day meeting, naturally fielded some questions about consumer price inflation, which the Fed expects to hit 4.2% this year, based on the median of board member projections. That’s way up from the sub-2% levels of 2019. But with supply chain bottlenecks expected to ease, and labor markets expected to normalize, the Fed sees inflation falling back to 2.2% next year, right within target.

With respect to real (inflation-adjusted) GDP, the Fed now sees 5.9% growth this year, a climbdown from the 7% it anticipated in June. Why the greater pessimism? For two major reasons: 1) Covid turned out to be more disruptive, stunting the recovery in sectors like tourism and 2) supply chain bottlenecks, which seemed on track to ease but instead became worse, most importantly in the auto sector which can’t get enough of the semiconductors it needs. The Fed’s median GDP growth forecast for next year is 3.8%. For 2023 it’s 2.5%. Members have also turned slightly more bearish on the labor market, projecting the unemployment rate to be 4.8%, not the 4.5% figure they envisioned in June. They held to their forecast for a 3.8% jobless rate in 2022. It was3.7% in 2019.

Powell separately warned of “severe damage to the economy and to financial markets” if Congress fails to raise the debt ceiling, which would prevent the U.S. Treasury from repaying the money it owes on trillions of dollars in notes and bonds outstanding. No one should assume, Powell stated sternly, that the Fed can protect markets or the economy if Congress doesn’t act.

What else did Powell cover in his press conference? He addressed the thorny ethical issues associated with FOMC board members trading financial assets. The U.S. economy, he added, doesn’t have any direct exposure to the Evergrande crisis playing out in China (though the Fed maintains a watchful eye on how the Chinese debt situation might affect global financial markets). He declined to answer a question about the likelihood of his own reappointment.

On a technical note, the Fed is currently paying banks 0.15% interest on the reserves they keep at the Fed. And it’s charging 0.25% on loans that banks take from the Fed (the primary credit, or “discount” rate). These would be emergency loans, in keeping with the central bank’s core function of acting as a lender of last resort in times of crisis. Discount rate lending is only available to U.S. banks, however, and the Fed has more recently established emergency lending facilities to other key actors in the giant and vital short-term dollar money market. They include foreign central banks (which need U.S. dollars every bit as much as U.S. banks), primary dealers (which in normal times are always there to buy and sell Treasuries) and short-term money market investment funds.

Companies

US Bancorp: America, as of June 1, had 8,145 banks (institutions insured or supervised by the FDIC). Twenty years earlier, it had 15,099 banks. Now, it’s about to shrink by one more. Last week, the country’s fifth largest bank, Minneapolis-based US Bancorp, announced its intention to buy most of MUFG Union Bank—that’s the U.S. arm of Japan’s Mitsubishi. MUFG itself bought Union Bank in 2008, creating what’s today the 28th largest U.S. bank by assets. After the deal, assuming regulators approve it, US Bancorp will remain in the number five position, behind the four giants of New York and Charlotte: JP Morgan (New York), Bank of America (Charlotte), Wells Fargo (Charlotte) and Citi (New York). But will in fact regulators approve it? The Biden administration is keen to slow the pace of consolidation in American business, arguing that fewer competitors mean higher prices, less innovation, fewer opportunities for small businesses and declining consumer welfare. If it does go through, however, US Bancorp will strengthen its position in the lucrative California market, and the west coast more generally. In Los Angeles, for example, it will become the fourth largest bank by deposits. In San Diego, it will become number three. Executives made clear that this deal doesn’t diminish their interest in also expanding eastward, eyeing fast-growing markets like North Carolina. It’s also growing in the east via a partnership with the insurer State Farm. Roughly three-quarters of MUFG Union’s loans, incidentally, are for real estate purchases, both residential and corporate. US Bancorp itself has a more diverse array of activities, issuing credit cards, providing wealth management products and investing heavily in payment services. It of course lends heavily to both businesses and households too, competing with other banks and non-bank lenders like the mortgage powerhouse Rocket.

American Airlines: It’s not just idle talk. The Biden administration really is pursuing a policy of aggressive antitrust enforcement, and not just with respect to Big Tech. Earlier this year, the Justice Department (DOJ) sued to block a big insurance merger (between Aon and Willis Towers Watson, the two of which subsequently abandoned their deal). Now another move: The DOJ last week, joining six states and the District of Colombia, sued American Airlines to stop it from forming an alliance with rivalJetBlue. Regulators are concerned about the likely effects on competition in the U.S. northeast, especially in New York and Boston, two of JetBlue’s largest markets. They’re more generally concerned about the U.S. airline industry as a whole, where four airlines—American, United, Delta and Southwest—now carry more than 80% of all domestic passengers. By law, foreign carriers are not permitted to compete on domestic routes. Before 2008, the concerns were just the opposite: an excessively fragmented airline industry in which companies struggled to survive and avoid constant layoffs. Then came five big mergers: Delta-Northwest, United-Continental, Southwest-AirTran, American-US Airways and Alaska Airlines-Virgin America. That stabilized airline earnings during the 2010s, before the industry smashed headlong into the Covid crisis last year. There are, to be sure, a few sizeable low-cost carriers driving down industry prices on most major domestic routes—Spirit (Fort Lauderdale), Frontier (Denver) and Allegiant (Las Vegas) are some examples. JetBlue is another, but would it no longer be as useful to consumers in driving down airfares if closely tied to American? Clearly, the DOJ and its fellow litigants think so.

Lennar: The Miami-based homebuilder reaffirmed the dominant narrative of the U.S. housing market in 2021: “The story remains that supply is short, and demand is strong.” Executives mentioned price and procurement headaches for items like engineered wood, windows, garage doors, paint and vinyl siding. Some markets like Phoenix and Minneapolis are experiencing severe labor shortages. Others like Texas don’t have sufficient lumber and brick. In addition, many municipalities don’t have enough personnel to conduct safety inspections and permitting. There are signs that housing prices, still up sharply versus last year, are starting to cool. Lennar, however, downplays the significance, expecting home prices to remain firm thanks to years of underproduction. Demand, meanwhile, continues to get a boost from low mortgage rates. As for hot housing markets, the company highlighted Naples, Sarasota, Tampa, Miami and Fort Lauderdale in Florida. Orlando too, is seeing a strong recovery as tourists return. It also mentioned Phoenix, Las Vegas, Raleigh-Durham, Charlotte and Charleston. California too, despite an especially severe housing shortage, has hot markets like the Inland Empire, Sacramento and the East Bay area. Parts of Texas are strong too.

FedEx, the Memphis-based logistics giant, added to the chorus of companies unnerved by frayed supply chains yet still earning strong profits. Its profits did drop, though, with “constrained labor markets… the biggest issue facing our business.” Wages are up. But more importantly, understaffing creates costly inefficiencies. Portland, Oregon, a key hub, is operating at just 65% of its normal staffing. It’s this uncomfortable reliance on America’s undersupplied labor market that’s motivating FedEx and many other U.S. companies to up their capital investments on automation—capex is indeed up sharply this year. Just last week, FedEx announced a new partnership to develop driverless vehicles.

Tweet of the Week

Sectors

Finance: “Anyone can be a banker these days, you just need the right code.” This was the leading sentence of a Reuters article published on Sept. 17, which sounds like it might be about decentralized finance and the cryptoeconomy, i.e., using blockchain-based platforms like Ethereum to offer financial services. But no, it was about something else, something even more threatening to banks presently. Retailers, Reuters explains, are increasingly offering financial services like loans and insurance to their own customers, often with help from software companies capable of analyzing customer data. Walmart is doing it. Amazon is doing it. Automakers are doing it. And so on. Square is one company helping retailers provide financial services, and it’s now worth more than Europe’s most valuable bank (HSBC). The retail platform Shopify, based in Ottawa, has its own lending arm. And the company is now worth more than Canada’s largest bank (Royal Bank of Canada, or RBC). Banks, to be sure, are not sitting idle. Goldman Sachs, for one, is providing credit card lending for Apple, the giant of mobile device retailing. JP Morgan recently bought control of Volkswagen’s payments business. Not that this is totally new—Sears began issuing Discover credit cards in the 1980s. But bottom line: If you own valuable data on consumers, or own software capable of crunching that data, you’re positioned well in today’s economy.

Autos: A quick update on auto sales from Sam Fiorani of AutoForecast Solutions. He provides some figures in an interview with Automotive News: In 2019, global auto sales reached 90m units. The number fell to 75m last year due to factory closures early in the Covid crisis. As demand roared back in 2020’s second half, it looked as if that 90m mark would be reached again in 2021. Alas, in stepped the semiconductor shortage, reducing expected output this year to just 81m units.

Markets

Labor: It’s one of the great mysteries of the U.S. economy, and one with profound implications for present and future GDP growth. Why are so many working-age American men—a third of them, in fact—not working. That’s almost 30m people. And it’s not something that just transpired during the pandemic. Far from it. The labor participation rate among males peaked in 1949, at 87%. Today, it’s 68%. Andy Serwer and Mex Zahn addressed the mystery in an article last week. It’s also a subject think tanks like the Brookings Institution have been pondering for years. Some possible reasons:

Early Retirement: Sewer and Zahn focus on municipal government workers, who make up nearly 14% of the entire U.S. workforce. These jobs can offer generous pensions to workers younger than the standard retirement age of 64, meaning they’d be counted in the workforce even if retired. The authors cite Census data showing some 6,000 public sector retirement systems in the U.S., collectively holding $4.5 trillion in assets. These plans have 14.7m working members and another 11.2m retirees, distributing $323b in benefits annually. In almost two-thirds of these plans, if you started working at 25, you max out at 57, a major inducement to stop working at that age.

Rising Asset Prices: As Charlie Bilello of Compound Capital points out in a Tweet, Bitcoin returned 994,608% in the ten years to Sept. 19. That alone created wealth for many a male day trader. Others earned enough money to avoid work by investing in stocks like Tesla or Netflix. Buying and holding the S&P 500 for long enough would have done the trick too. In addition, rising home prices gave many Americans the opportunity to sell their homes at a big profit. Some certainly used this profit to pay for a pricier home. Others downsized or moved to a cheaper city, providing leftover cash to finance a lifestyle without work. Saving rates are also up thanks to government stimulus.

Stay-at-Home Dads: Notwithstanding a big drop during the pandemic, female workforce participation has risen in recent decades, which affords more males the option of taking on unpaid (and uncounted) domestic work like childcare.

A High Incarceration Rate: It means not only many males behind bars but also many males unable to find work after release—companies are often reluctant to hire people with criminal records.

The Illegal Drug Trade: Nobody really knows how big a business this is. But estimates can range in the hundreds of billions. Somebody’s got to do the legwork, and those who do won’t (for obvious reasons) show up in the participation statistics. With opioid use spiking during the pandemic, job opportunities in the drug trade are likely plentiful. There are other illegal sources of income of course, ranging from shoplifting to insurance fraud. Some people simply work under the table, collecting incomes that go untaxed and unreported.

Living with Relatives: Serwer and Zahn note that in July, 52% of young adults resided with one or both of their parents, up from 47% in February. It doesn’t mean these people weren’t working. But not working is easier when most of the bills are covered.

Living off the Land: Sounds unreal but at least some males seem to be getting by through growing or catching their own food. Data on activities like fishing and seed sales indeed show large increases.

Government Benefits: Some 9m Americans are receiving disability insurance from the Social Security Administration, many of them before retirement age. Unemployment checks too, might be enough for some males to temporarily eke out an existence, perhaps in combination with other sources of off-the-books income.

Education: The Wall Street Journal just ran a much-talked-about report on how colleges are finding it tougher to attract male students. In 2016, David Wessel of Brookings said 9.3m men aged 25 to 50 weren’t working, 5.3m of which had nothing beyond a high school degree.

Use of Painkillers: That same year, according to Wessel, 40% of men not working (or not actively looking for work) reported taking pain medication every day, compared to just 20% of those in the workforce. As mentioned above the opioid epidemic has only gotten worse with the pandemic.

Other Reasons: One study from a few years ago blamed increasing rates of young male idleness on video games. Mental illness or disabilities among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans might be a factor. America’s notorious litigiousness might mean sizeable of numbers of males living off lawsuit money from medical malpractice or class-action suits.

Final thoughts: The answer to the mystery probably involves a combination of these explanations, even for individuals. Here’s Serwer and Zahn again: “Take for example a hypothetical guy in a rural area who lives with his grandmother rent free, (he does help her with the garden some). This guy also does some cash carpentry work, hunts for game, gets some food off his ex-wife’s WIC and helps his brother sell some weed.” Of course, the early retirees and Bitcoin Billionaires fit a different mold, emphasizing the point that the causes are probably diverse. Keep in mind: The economy of the 1980s through 2010s was tough on traditionally male denominated manufacturing jobs, many of them outsourced, automated and sent overseas. A lot of the growth that replaced the manufacturing sector, meanwhile, came from care economy jobs traditionally held by females, i.e., health care, childcare and eldercare. If there’s one mental image that captures this shift, picture a factory closing and a hospital sprouting in its spot.

Government

Monetary Policy: Writing in RealClear Markets, investor Ken Fisher argues that “quantitative easing isn’t stimulus, and never has been.” He’s talking of course about the Fed’s policy of essentially creating lots of new money by buying bonds, which it began pursuing after the last financial crisis. In the past, the Fed would lower interest rates to stimulate the economy but after 2008, interest rates have been close to zero. A common misunderstanding is that quantitative easing leads to inflation—more than a decade of real-world experience shows that’s not the case. A key insight, as Fisher writes, is that the Fed isn’t just creating any type of money but a specific type of money, namely non-circulating reserves that banks merely use to settle debts with each other. The Fed flooded the banking system with this reserve money, getting Treasury bonds in exchange. Bond prices thus rose and conversely, interest rates dropped. In the Fed’s eyes, this was a good thing: lower interest rates helped stimulate economic activity. It meant more people could afford homes, cars and appliances. Companies could afford to invest in new projects. Here’s the problem, says Fisher: When interest rates drop, it wreaks havoc on bank profitability, which means they’re inclined to lend less, not more. So sure, reserve money was created in great quantity. But the more important form of money—new bank deposits—actually shrank throughout the 2010s. That’s why Fisher sees quantitative easing as deflationary, not inflationary. The only area that winds up being inflationary are asset prices, be they stocks, bonds or houses (though house price inflation has a lot to do with the separate issue of insufficient supply, just as the currently high rate of inflation has to do with supply-side issues). What would the Fed say? That quantitative easing was necessary to drive down rates, without which fewer households and businesses would borrow. You can see the debate: Is it more impactful to get demand for borrowing up through low interest rates, or to get supply of lending up through high interest rates? The discussion becomes even more complicated when considering that those Treasury bonds the Fed is taking from the banks are a form of money too, in this case no longer available for use as collateral in global lending markets. That’s why ironically, in a time when the Fed is flooding the banking system with new dollars, some argue the world is experiencing a major dollar shortage.

Monetary Policy: In undertaking its big increase in quantitative easing last spring, the Fed wound up buying about 5% of the entire $20 trillion Treasury market in just a matter of weeks. Adam Tooze of Colombia University, promoting his new book on the Ezra Klein podcast, recounts the Fed’s terrifying predicament in March 2020, when the market began dumping Treasuries to secure cash. This was scarier than even in 2008, when the market was dumping everything except Treasuries—everyone wanted Treasuries then because they’re considered totally safe. Just as good as cash. Normally, Tooze says, U.S. Treasury debt is like the “piggy bank” of the global economy, a safe place to store value. But suddenly last spring, if you wanted to sell Treasuries you couldn’t find a ready buyer. Ultimately, the Fed stepped in as the Treasury buyer of last resort, complementing the traditional central bank role of lender of last resort. It continues to buy $80b worth of Treasuries a month, plus $40b of mortgage-backed securities implicitly backed by the government. Soon, though, it will begin to reduce, or taper these purchases (see coverage of last week’s Fed meeting above).

Places

Franklin County, New York: It shares a name with the world’s richest and most powerful city. But in the farthest northern reaches of New York state, the world looks a whole lot different. In Franklin County, New York, which borders Canada, the worries don’t involve soaring rents or unreliable subway service. There, the worries are more typical of troubled rural America, where populations are shrinking and economies struggling to create good jobs. Indeed, Franklin County’s population dropped by 3% during the 2010s, even as the U.S. population grew 6%. In 2015, the aluminum maker Alcoa closed a nearby plant that extinguished about 500 jobs from the area. In 2017, the now-famous drug giant Pfizer closed a plant, costing the region 120 jobs. The county is heavily dependent on the public sector, which accounts for more than half of total employment. Particularly important are several correctional facilities (that’s another term for prisons). Even in this sector though, job opportunities have diminished, with one prison closing in 2014. Statistics on the county’s roughly 50,000 people make the region’s difficulties clear. Median household income is just $50,000, versus $63,000 nationally. The poverty rate is 18%, versus 11% nationally. Unemployment rates were above the national average before Covid. So was the prevalence of residents collecting disability insurance. According to 2017 data from Franklin County’s economic development plan, the percentage of 16-to-19-year-olds not in school, not graduated and not employed was twice as high than the national rate. Another challenge is geography. Fort Covington, which touches the Canadian border in the northernmost area of the county, is nearly 400 miles from New York City. Even Albany and Syracuse are hours away by car. Rural areas are gaining an advantage in the new world of remote working but only if broadband internet connections are fast and reliable—in Franklin County, that’s a problem. The area’s population, furthermore, is spread across a vast area, featuring the largest town Malone but also the Saranac Lake and Tupper Lake regions. The cold winters don’t help either—it’s the Sun Belt where people are moving, starting companies and taking jobs. Where do people in Franklin County work, besides correctional facilities? The largest private employer (with about 900 jobs) is the Akwesasne Casino on the Mohawk reservation. Native Americans, still 8% of the county’s population today, have a long history in the area. Non-Hispanic whites, meanwhile, account for 82% of the population, with foreign born residents just 3%. But back to employment, the health and education sectors are (welcome to 2021 America) important, accounting for 35% and 13% of all county jobs, respectively. Naturally, trade with Canada is important—Montreal is less than a two-hour drive from Malone. But the border was closed for an extended period due to Covid. That hurt. Though disadvantaged by geography, the area’s lakes and mountains attract a good number of tourists, including skiers during winter. Lake Placid, once the site of the Winter Olympics, lies just south of the county. Logging was once a much larger industry in upstate New York, before the days of foreign competition, product substitution, tougher environmental standards and skilled worker shortages. But what’s left of logging today is benefitting from a strong national market for homebuilding. Just an hour away in Plattsburgh is an airport with lots of low-fare flights. Not far west is the water port of Ogdensburg, an important trading gateway on the St. Lawrence River. Franklin County could benefit if only it could get a rail link to the port, which would also connect with the major CSX rail line to Syracuse and beyond. One of the area’s biggest draws, meanwhile, is some of the cheapest electricity rates anywhere in the country, supported by abundant hydro and other clean power. Unfortunately, the current power grid doesn’t support the ability to export surplus power to New York City. But it does offer power-hungry businesses, including cryptocurrency miners and data storage operators, an important advantage. Development officials also trumpet the county’s affordable housing and surplus labor at a time of severe shortages. This includes many experienced military veterans, correctional officers and former employees of Alcoa and Pfizer. The correctional officers, interestingly, also happen to retire at an early age on average, and many might be interested in pursuing second careers. Is this enough? To be frank about Franklin, the county is part of forgotten America, worlds away from the nation’s economic engines and migratory magnets. But it’s not without economic assets, cheap power most intriguing among them.

THIS IS AN ABBREVIATED VERSION OF THIS WEEK’S ISSUE. TO SEE THE WHOLE ISSUE, INCLUDING A LIST OF THE TOP EMPLOYERS FOR U.S. CITIES, SEE WWW.ECONWEEKLY.BIZ (IT’S FREE AND OPEN TO READ THIS WEEK)