Inside this Issue:

Titanic Tech Takings: More Giant Profits for Big Tech’s Big Five

Still Not Time to Taper: Though Inflation Fears Heighten, Fed Won’t Yet Tighten

Growing GDP with Stim from Wash D.C.: Economy Now Bigger than it Was Pre-Crisis

Shaking Hands on Building Plans: Senate Deal Advances Infrastructure Program

Elon’s E-Cars: Strong Q2 Profits for Tesla

The Vetocracy: America Can’t Erect Anything, Because Americans Can Reject Anything

Johnny’s Cash: Who Were 2020’s Highest-Paid Musicians?

Call Care Despair: The Dark Underside of Phone Agent Labor

From Zero to Hero: Marvel’s Stunning Rise from Bankruptcy

Using Your Mind: Brain Signals as a New Computer Interface

And This Week’s Featured Place: Bend, Oregon’s Tahoe

Quote of the Week

“This was a good quarter for our product and business. There are now more than 3.5b people who actively use one or more of our services.”

- Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg

Market QuickLook

The Latest

Corporate earnings. A big Fed meeting. New reports on GDP and inflation. Where to begin?

Start with Big Tech, whose Q2 profits were again nothing short of prodigious. The Big Five of Silicon Valley and Seattle collectively mustered $340b in revenue (see chart below) and $86b in operating profits—that’s just for April, May and June. Their combined operating margin? 25%, with average revenue growth of 44%. Prodigious, indeed.

Big Tech’s world, of course, spectacular riches aside, isn’t worry free. Big Government isn’t happy about its expanding power and influence, sensing harm to consumers, workers, small businesses and democracy itself. Apple, for its part, can’t be feeling so comfortable about its deep ties to China, a country Washington sees more and more as an enemy power. Make no mistake: Apple, Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Facebook are creators of great wealth for the economy, investing billions and employing millions (directly and indirectly). But so too were breakup targets of the past, including Rockefeller’s Standard Oil and AT&T. Don’t forget about Microsoft itself, an antirust bad boy of the 1990s whose takeover moves today—look at its $20b deal to buy Nuance—hardly ruffle a feather.

AT&T, too, is today a less menacing presence, likely unperturbed in its plan to merge Warner Media with Discovery. Nevertheless, Washington’s trustbusting proclivities are on display. Last week, the insurance giants AON and Willis Tower Watson, facing Justice Department litigation, abandoned their planned merger. Still to come are battles over controversial combos including Nvidia’s takeover of ARM and Canadian National Railroad’s acquisition of Kansas City Southern. Will Amazon’s acquisition of MGM Studios evade a regulatory challenge?

Turning to the challenge of Jerome Powell, he—the chairman of the Federal Reserve—made clear for the umpteenth time that the needs of a convalescing labor market take precedence over the threat of persistent inflation. At the latest Fed policy meeting last week, not much changed. The Fed certainly isn’t ready to lift interest rates. But nor is it ready to even pull back on monthly asset purchases. A pullback could come soon, however, perhaps later this month when Powell delivers a speech at an event in the mountains of Wyoming.

Mountains of debt aren’t deterring Congress from advancing legislation to invest in infrastructure. A Senate compromise makes that more likely but still not certain. Proponents say the money will come from various sources including pools of already approved Covid relief funds. There’s a much larger spending proposal, meanwhile, that the Biden administration hopes to pass alongside the infrastructure bill. Complicating the debate about deficit spending is the long record of wantonly engaging in such spending—over and over again—without any inflationary or interest rate repercussions.

Unless that is, you believe the current rates of inflation spell trouble. Rising input costs are a major theme of Q2 corporate earnings calls, specifically for raw materials and shipping. Some of this is indeed getting passed to consumers, as the Commerce Department’s latest personal consumption expenditure (PCE) index clearly shows. June’s reading was up 4% y/y, double the Fed’s traditional 2% inflation target. The one-month increase (from May to June) was 0.5%. Energy continues to be the biggest driver of rising prices, followed by durable goods, notwithstanding a shift of some spending toward services.

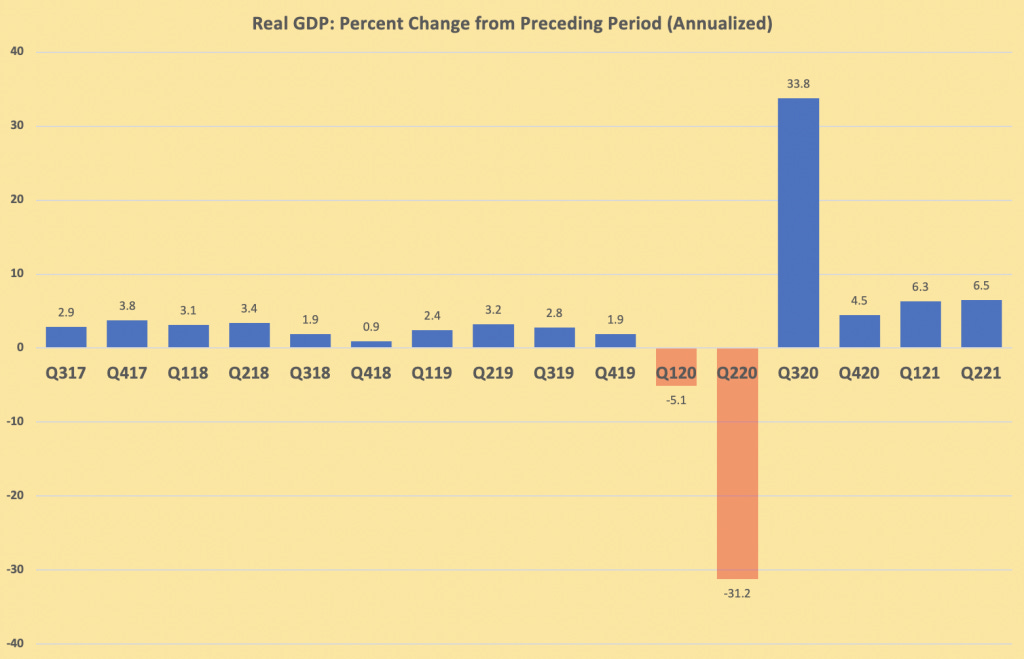

The Commerce Department separately published its latest GDP estimates last week, showing 6.5% annual growth for the second quarter. That follows 6.3% growth in the first quarter. One key takeaway is that the U.S. economy is now larger than it was before the pandemic started. That said, it’s still smaller than it likely would be had the pandemic not happened. It’s also smaller than it would have been absent severe supply chain pressures and input shortages, of everything from truck drivers to semiconductors. As for 2021’s second half, the U.S. economy might have to get by with less fiscal and monetary rocket fuel. Rising prices, furthermore, could dent consumer spending power. But assuming the housing market remains strong, and the latest wave of Covid doesn’t interfere, GDP appears positioned for ongoing expansion.

In other news, Robinhood—call it a champion of the small investor or a financial casino—is now a publicly-traded company. In a welcome development, the Urban Institute says the poverty rate will be below 8% this year, a big drop from 14% in 2018 (the sharpest drop is among children). Investors expressed some concern about the slowing pace of e-commerce, hitting shares in Amazon and UPS. A new book claims Tesla talked merger with Apple. A moratorium on housing evictions ended. So has Washington's temporary suspension of the debt ceiling.

This week: Another busy one, with a Friday jobs report due, plus another long list of corporate earnings.

Tech Titan Might

Companies

Tesla, a company known for its revolutionary cars, not its profits, earned a rather sizeable profit in the second quarter. Its net result topped $1b in fact, on production and delivery of more than 200,000 vehicles. Like other automakers—and makers of pretty much anything high-tech for that matter—Tesla was adversely affected by a shortage of semiconductors. Demand for its electric cars, however, remains bullish. “At this point,” said the iconic company’s CEO Elon Musk, “I think almost everyone agrees that electric vehicles are the only way forward.” Tesla continues to advance toward its goal of selling completely autonomous cars, which Musk insists will be safer. He invokes the memory of early human-operated building elevators, which were prone to accidents, deaths and serious injuries. Automation in that case led to much greater safety.

Google, also known by the name of its parent company Alphabet, is an advertising company. There’s no escaping that fact. Like Facebook, it knows (through your online activity) that you love purple sweaters. So Purple Sweaters Incorporated will happily pay up to show you an ad. But clearly, Google would like to diversify its revenue base. It has a longterm bet on providing cloud computing services, still a money loser. It has even longer-term bets on quantum computing and autonomous cars (Waymo). More immediate diversification comes from the growth of subscription revenues, most notably from YouTube. The video platform, to be clear, is primarily an advertising engine for Google. But people are increasingly paying for services like YouTube TV as well. Facebook, for its part, is also trying to envision a world beyond advertising, speaking a lot lately about an immersive, virtual reality-heavy computing environment Mark Zuckerberg calls the “metaverse.” Remember: Without a phone platform like Google has with Android, Facebook is even more deeply reliant on people using its apps on Apple’s platform. And this hurt when Apple made it more difficult for app-makers to collect personal user data. Apparently, it wasn’t too hurtful though. Did you see Facebook’s operating margin last quarter? (See chart above).

Comcast, based in Philadelphia, is a leading provider of high-speed internet and cable television, competing with companies like AT&T and Charter Communications. It’s a media giant as well, with ownership of the NBC broadcast network, the Spanish language network Telemundo and cable channels like the USA Network, E!, MSNBC and CNBC. It also owns Universal Pictures, the Sky Network in Europe, Universal Studios theme parks and the new streaming platform Peacock, among other properties. Peacock, incidentally, is off to a strong start in terms of new sign-ups, aided by exclusive U.S. coverage of the Tokyo Olympics. Rights to Monday Night Football should be another big draw in the fall. Is it enough to compete in a crowded field of streaming products, led by Netflix? Comcast thinks so. In the meantime, its U.S. theme park business is recovering, with Orlando enjoying “exceptionally strong demand.” Things are slower at Universal Studios in Tokyo, however, and uncertainty runs high just months before a new park opens in Beijing.

Tweet of the Week

Sectors

Housing: It’s arguably one of America’s biggest policy challenges: What to do about the severe shortage of housing? Jerusalem Demsas, a reporter with Vox, is an expert, sharing her thoughts in various media appearances. One thing she makes clear is that the current spike in housing prices doesn’t have any resemblance whatsoever to the price bubble that inflated in the mid-2000s. This spike is driven by pure supply (not enough of it) and demand (a big increase amid Covid living trends, millennials reaching a certain age, super-low interest rates, retirees no longer wishing to downsize to apartments and so on). She gives a figure that helps explain the affordability dilemma for middle class families: Today, just 7% of newly built houses are “starter” homes priced for young, average-income buyers. That figure was 40% in 1980. Simply put, builders find it more profitable to build homes for wealthier people. Going deeper, the housing shortage problem is aggravated by local zoning laws which often make it impossible to build new houses in a given community. It’s reached the point, Demsas says, where lower-wage workers can’t take advantage of the many good jobs available in big cities, because the cost of living there outweighs the higher wages they’d earn. That throws a wrench into the healthy process of labor migration, exemplified by decades of manufacturing belt workers moving to the sunbelt. (Think of a laid-off auto factory worker moving to Las Vegas for a unionized casino job). Another cause of the housing shortage problem, Demsas explains, is how easy it is to stop or slow new building projects—this includes transportation projects too, including those that would make it feasible for people in lower-cost neighborhoods to commute to big city jobs. Citizen and activist veto power is immense, through use of lawsuits and redundant environmental reviews, all of which drive the cost of construction to levels way beyond those of even cities like Paris. It echoes a central thesis of Harvard professor Francis Fukuyama, who says America has become a “vetocracy” in which anyone is able to block anything. There are state and federal efforts to address local NIMBYism, the not-in-my-backyard sentiment widespread in wealthier communities. But as you might imagine, taking power away from local communities is controversial.

Housing: Some numbers from the Congressional Research Service: In 2020, the combined number of homes sold in the U.S. was about 6.5m, the highest figure since 2006. (Roughly 86% of these were sales of existing homes; the rest new homes). Investment in residential real estate, meanwhile, was $885b in 2020, with another $2.8 trillion spent on housing services (i.e., rents, utility bills, etc.). Together, the housing sector accounts for an estimated 17% of GDP. Let’s say that again: Housing is 17% of the U.S. economy. That’s why what happens in housing doesn’t stay in housing.

Music: Billboard presents a list of its 2020 “Money Makers” in music, led by the pop star Taylor Swift—she earned $24m last year. But this was down from the $100m she earned in 2018, the last time she made the list. It was unsurprisingly a tougher year for most musicians, given the suspension of concerts during much of the pandemic. Who else made Billboard’s list? Post Malone was number two, followed by legacy acts like Celine Dion, the Eagles, Queen and the Beatles. Mixed in were other more contemporary acts like Billie Eilish, Drake, Lil’ Baby and YoungBoy Never Broke Again. Econ Weekly assumes you know who all these people are. If not, you’re just not cool.

Call Centers: One critique of modern American capitalism is that major corporations, while often upholding higher standards of labor practices than in previous generations, still rely on unfair and even abusive practices—they just let contractors do the dirty work. Don’t want to provide health benefits to custodians or customer service workers? Outsource the job to staffing agencies. Need cheaper labor than what’s possible given U.S. labor laws? Find a partner in China. Even the big U.S. airlines outsource much of their flying to regional contractors who pay their pilots much lower wages; lots of their aircraft maintenance is outsourced too, to places like El Salvador. The counterargument, of course, is that without such practices, the U.S. economy would be a whole lot smaller, with less money to go around for everyone. All of this is a prelude to mentioning a ProPublica investigation of work by outsourced at-home customer service phone line workers. It paints a dark picture of agents facing extremely abusive callers, who know there’s no accountability for anything they say. The work can take a psychological toll, made worse by corporate directives to always appease customers no matter what. The article describes it as “a largely unseen industry that helps brand-name companies shed labor costs by outsourcing the task of mollifying unhappy customers.”

Markets

Labor: The Labor Department said the U.S. added 8.8m new jobs during the fourth quarter of 2020, while losing 6.7m. That’s a net gain of more than 2m. The net jobs gain in the third quarter of 2020 was 3.9m, which followed a brutal net loss of 14.6m in Q2, when Covid first struck. Separately, the Department released unemployment rates by metro area for June of this year, showing Las Vegas and Los Angeles still registering the highest figures—both have unemployment rates close to 10%. The national unemployment rate, remember, currently stands at 6.1%, though an update to that figure will be included in the July employment report coming this Friday (Aug. 6).

Quarterly GDP Growth

source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

Government

The Senate reached a bipartisan compromise on infrastructure investment, with support from President Biden. According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB), the plan calls for $550b of new spending, with roughly half for transportation and the rest for things like the electric grid, clean water and broadband. Roads and bridges would see the greatest amount of funding ($110b). Will there be new money to pay for these investments? Well, the plan aims to raise some new money, from sources like reducing unemployment fraud and collecting taxes on cryptocurrency holdings. Some money ($205b, the CRFB says) will come from funds already available through previous Covid relief legislation. There’s some squishiness in the numbers, though, which makes deficit and debt hawks uneasy. But Washington is increasingly populated by fiscal doves, downplaying the threat of high deficits. Within this group are people who still believe deficits matter, just not urgently enough to neglect critical investments. Also within the group of doves are modern monetary theorists who dismiss the threat from federal debt altogether—as long as sustained inflation isn’t a problem, they argue, a government that prints its own currency can borrow as much as it wants. But back to the Senate’s infrastructure compromise: It’s not a done deal yet. To become law, it needs full Senate and House approval, which is hardly assured. President Biden remember, is pushing for two big spending bills, one on hard infrastructure and another much bigger package ($3.5 trillion) focused on climate and the care economy.

Places:

Bend, Oregon: It’s small by city standards. But perhaps not for long given current growth rates. Bend, an Oregon city southeast of Portland, saw its population grow an astounding 25% during the 2010s. And the 2020s are off to just as vivacious a start, with Bend appearing regularly on rankings of top places for resettlement and remote working during the pandemic. In fact, among the nearly 400 metro areas tracked by the U.S. Census, Bend’s 25% growth last decade was topped by only six other places (The Villages, Austin, Myrtle Beach, Midland, St. George and Greeley—in Florida, Texas, South Carolina, Texas, Utah and Colorado, respectively). Why are so many people coming to Bend? For some the lure is affordability—many newcomers are people priced out of nearby Portland or other expensive cities like San Francisco and Seattle. Some are high-income tech workers buying second homes from which to work remotely. Some compare Bend to Aspen or Lake Tahoe, two better-known resort towns popular with prosperous westerners. Tourism, sure enough, accounts for about 17% of Bend’s economy, according to EDCO, an economic development group for Central Oregon. Its chief Roger Lee, like all econ development leaders these days, speaks of Austin as the holy grail of development success. But in Bend’s case, Boulder is more apt for comparison given its size. Even Boulder though, has an easier time attracting businesses thanks to how close it is to Denver (just 30 minutes by car); Bend is more like three hours from Portland. Still, the area is attracting smaller industries and companies, including some in the cannabis sector. Natural foods is another important sector for Bend, which is home for example to Laired Superfood. The city has small tech startups too, including several focused on video games. The biggest employers, however, are the city’s resorts, led by Sunriver. Bend’s largest employer of all is St. Charles Health System—here again an example of just how vital health care is to the American labor market. Ditto for education and government; Central Oregon Community College, a public school, is Bend’s third largest employer after St. Charles and Sunriver. Another big employer—the manufacturer Bright Wood—lies just north of Bend in Madras. Unsurprisingly, Bend’s affordability is now challenged by soaring home prices. Lee points to nearby Prineville, just 35 miles away, where home prices are much cheaper. Oregon in general has a stark urban-rural divide, and a history of tense political fights over environmental measures that have in some cases hurt the state’s important timber and logging industry. A final demographic note about Bend: Its population is 93% White, compared to 87% for Oregon as a whole and 76% for the entire U.S.

New Jersey: Feeling lucky? James Carey Jr., executive director of the New Jersey lottery, tells journalist Steve Adubato that ticket sales have been at record levels during the pandemic. Why? One theory is that casinos were closed for a long time, as were other places to spend entertainment dollars, including restaurants and bars. Where, by the way, does money from lottery tickets go? Carey says $1b goes to the state’s pension system for government workers. It’s used for education as well. The wider context is that New Jersey’s typically troubled state finances are (like those of all other states right now) in unexpectedly good health thanks to Federal aid, a recovering economy and rising asset prices (i.e., real estate and stocks). The state is one of America’s wealthiest, squeezed between two massive metros (New York and Philadelphia) with giant pharmaceutical, financial, education and medical sectors. According to the economic development group Choose New Jersey, the state’s largest employer aside from hospitals and universities is United Airlines—it operates a major hub at Newark airport. Johnson & Johnson is next.

Abroad

China’s Auto Sector: As China’s government bears down on its tech sector, auto companies are watching nervously. China’s giant car market is critical for the world’s top automakers, with non-Chinese firms still in command of more than half the Chinese market. They are losing share to local producers however, as Autoline Daily informs. Germany’s Volkswagen ranks number one by market share among foreign automakers in China. General Motors is next, followed by Japan’s Toyota, Honda and Nissan. It’s an important market to Ford as well.

Abroad

U.S.-China Relations: Infrastructure compromises notwithstanding, there isn’t much bipartisan consensus in Washington these days. But few things bring Republicans and Democrats closer together than hostility toward China. Be careful, warns Steve Orlins of the National Committee on U.S.-China relations. Yes, Chinese policies on issues from Hong Kong to military expansion to Uighur rights are alarming and upsetting. But “we should not understate the benefits that constructive engagement has brought to the American people.” China, after all, has become more a part of the international system still led by the U.S. And it’s today the largest contributor to global economic growth. China supported U.S. efforts to sanction both North Korea and Iran. It helped end the Darfur genocide in Africa. It played a role in containing the Ebola epidemic, reducing piracy in the Aden Gulf and aiding the economic recovery after the 2008 crisis. Importantly, amid all the controversy and allegations about China’s role in the Covid crisis, the country remains an important partner in joint public health research. Orlins also reminds Americans that no U.S. soldier has died on an East Asian battlefield in the era of U.S.-China engagement—the region was a slaughterhouse for Americans pre-engagement (World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War…). Today, hostility to China is popular with voters. But President Nixon didn’t go to China based on an opinion poll. And nor was public opinion the driver of President Carter’s decision to establish diplomatic relations.

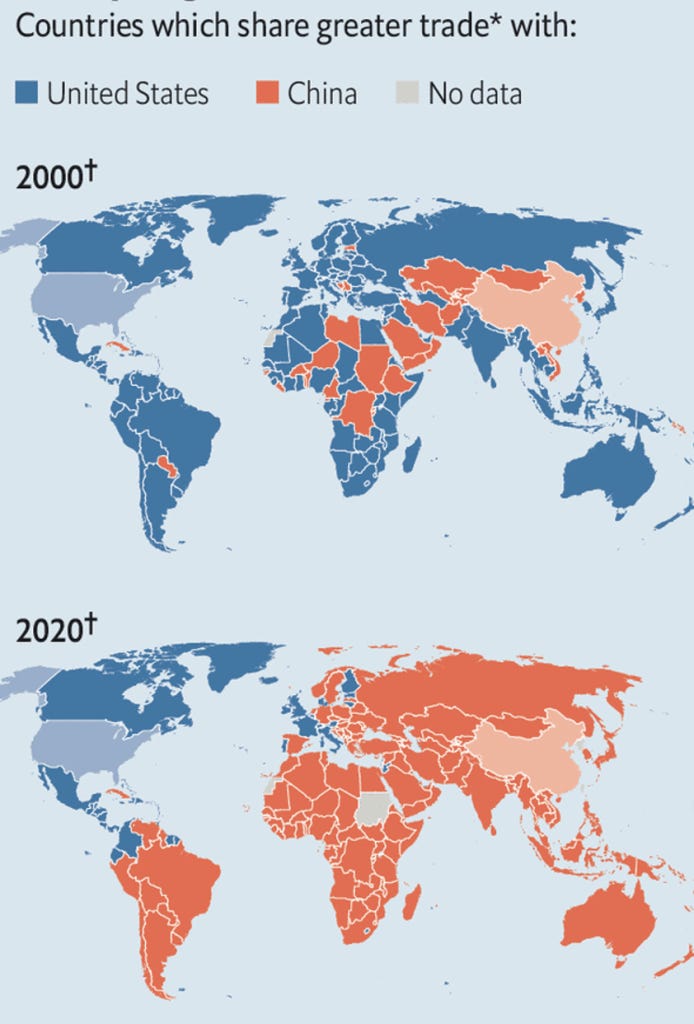

From The Economist: Who's Your Bigger Trading Partner? The U.S. or China?

Looking back

Marvel: “Thrilling Tales of Modern Capitalism,” a podcast from Slate, looks back at the remarkable ups and downs of Marvel, the comic book empire that wound up taking Hollywood by storm. The company’s history dates to the late 1930s, after a company called Detective Comics, or DC, produced a big hit with a comic book called Superman. But aside from some World War II-era success with the super-solider Captain America, Marvel’s characters never really gained traction. During the 1950s, many deemed comic books a bad social influence, leading to crime and juvenile delinquency. Marvel got a boost in the 1960s, from a team of talented and creative new artists, along with a skilled promoter named Stan Lee. Soon, a distinguishing and popular characteristic of Marvel’s characters was their human-like flaws and real-world problems. When not fighting evil and using their superpowers, they talked and acted like regular people. They became, in other words, very relatable to readers. Nevertheless, Marvel failed in its attempt to launch popular television programs in the 1970s. The 1980s were better, with comic books suddenly becoming a collectible craze. But the frenzy petered out and boom turned to bust, forcing many comic book shops to close. Making matters worse, Marvel flopped big-time with its 1986 film Howard the Duck, never mind the involvement of Star Wars super producer George Lucas. A decade later, in 1996, Marvel filed for bankruptcy, kept alive under the control of an eccentric new shareholder named Isaac Perlmutter. A move in 1998—Blade—was mildly successful. X-Men in 2000 did better. And then came Spiderman in 2002, a huge box office hit, catering both to young fans and many who grew up reading Marvel comic books as kids. The problem was, Marvel was only licensing the rights to use its characters. Others made the movies and grabbed a big portion of the proceeds. Marvel now really wanted to make its own So that’s what it started doing, daringly borrowing $525m from Merrill Lynch, which required it to post the intellectual property to its entire catalog as collateral. Its first in-house film, Iron Man, was a giant success. In 2009, Disney acquired Marvel for $4b, a bargain in retrospect. The 2019 film Avengers: Endgame became the highest-grossing film of all time. To date, Marvel films have grossed $22b worldwide, more than Star Wars, James Bond, Harry Potter or any other movie franchise. As you can see though, the company has a long history of ups and downs. Are there downside risks ahead? One is simply that people get tired of its stories, and a new generation of movie watchers wants something different. Another is the economics of streaming, and whether they can support high-budget action films.

Reconstruction: The era of Reconstruction defined the aftermath of the Civil War. The North had to decide how to reintegrate the defeated and economically ravaged South. As Ron Chernow’s biography of U.S. Grant discusses, one policy decision with far-reaching consequences was allowing Southern states back in the Union with full Congressional representation. This actually gave them more influence in Washington than they had before the war because now, freed slaves were counted as a full person rather than three-fifths of a person as the Constitution stipulated—the three-fifths provision was officially abolished by the 14th amendment in 1868.

Reconstruction: One feature of the Reconstruction era was a military occupation of the South, in part to enforce new laws protecting the rights of freed slaves. But as Jeffrey Jenkins and Justin Peck explain in their new book “Congress and the First Civil Rights Era, 1861-1918,” occupying the South was expensive and often bloody. On the New Books Network podcast, they compare it to the U.S. keeping troops to maintain order in Iraq. The occupation would end in 1877, as part of a political compromise to settle a disputed presidential election. Republican Rutherford Hayes would get the White House and Democrats (a party then dominated by the South and immigrant groups like New York’s Irish) won an end to the occupation. Jenkins and Peck, however, raise another crucial reason for the withdrawal of federal troops: The Panic of 1873, triggered by European investors dumping U.S. railroad stocks. Congressional efforts to enforce justice for freed slaves began to lose support among the northern public, which became more concerned about the economy. Many asked why, in times of distress, was Congress spending so much money deploying the military in the South. The military, incidentally, would have a growing role in the West, clearing Native American tribes from lands coveted by companies and settlers.

Looking ahead

Brain-Computer Interfaces: Speaking with Princeton University’s Policy Punchline podcast, Dr. Jamil El-Imad of The Brain Forum discussed efforts to use brainwaves to interact with computers. For all the advances in computer technology during the past decades, one thing that hasn’t really changed is the practice of using a keyboard and mouse to tell a computer what to do. Why not our brain signals? El-Imad, who also runs a company called Neuroco, wants to bring affordable brain signaling software to the public. The idea is to convert these neural signals into commands that a computer can understand and interpret. But he’s also at pains to not overstate what the technology will be able to do. Don’t think of writing a text message by just thinking of it. That sort of application is pure sci-fi, he says. But the technology shows great promise in areas like health care and virtual reality. In fact, El-Imad and his team are working on a headset for people with epilepsy designed to predict a seizure in advance. Another application would help people unable to speak or use their hands to issue simple computer commands by blinking their eyes. This “neural-control interface” technology might help with improving concentration or treating depression. It’s also ripe for the virtual reality world, including entertainment applications. El-Imad thinks it won’t be long before every household owns a VR headset loaded with various tools, and not just games. But he cautions: New technologies often evolve in the opposite direction as people predict. He recalls his days as a student in the 1970s, when lecturers spoke about the likelihood that computers would mean people would eventually work just two or three days a week. Instead, the opposite happened: “We work seven days a week because we’re trying to catch up with computers.”