Are We There Yet?

Plus: This Week’s Featured Place: Cumberland County, North Carolina, Pentagon South

photo courtesy of www.VisitFayettevilleNC.com

Inside this Issue:

Are We There Yet? Might the U.S. Economy Already Be in Recession?

If So, It Doesn’t Show: Ever See a Recession with 3.6% Unemployment?

Stocks and Bonds Up, Oil Down: A Welcome Break from the Recent Ache

Cooling Housing: But Some Geographies Faring Better than Others

A Means to Avert Climate Despair? Removing Carbon from the Air

Appalachian Calculation: Hoping Prison Jobs Can Replace Coal Jobs?

20th Century Fox: How Taiwan’s Foxconn Became Vital to U.S. Manufacturing

20th Century Box: How Containers Changed Everything (and Nearly Killed New York)

And This Week’s Featured Place: Cumberland County, NC, Pentagon South

Quote of the Week

“While the market has cooled, it has clearly not stopped.”

-Lennar executive chairman Stuart Miller, on the current state of the housing market

Market QuickLook

The Latest

Will there be a recession? Might we already be in one? The gloom is growing.

Fed chief Jay Powell himself, speaking to Congress last week, presented a long list of demons, including high energy prices, ongoing supply chain problems, slowing business investment, a softening housing market, tightening financial conditions, a slumping stock market and of course, intolerably high consumer price inflation. But he also said forcefully: “The American economy is very strong and well positioned to handle tighter monetary policy.” The extremely tight job market attests to that. So do resilient industrial production and consumer spending, even if softening a bit.

The next big clue on where the economy is headed? This week’s release of May inflation data based on personal consumption expenditures (the PCE index). If it reveals signs of inflation cooling, then perhaps the Fed’s next policy move will lean more dovish. If alternatively, May’s PCE inflation figure comes in high, Mr. Powell and his colleagues might feel compelled to squeeze the economy tighter.

Markets for the moment seem to think that future rate hikes could be less aggressive, not more. Last week, stock prices were up, and so were bond prices. Housing prices, meanwhile, are softening in many markets as nationwide sales volumes decline (see the Companies section below). The latest Census data for May showed a 6% y/y decline in new home sales (seasonally adjusted), with severe drops in the Northeast and Midwest balanced by small gains in the West and South. Keep an eye on The National Association of Realtors, which will publish its May data on pending home sales this week (on Monday). They’ve been declining for six consecutive months now.

Also declining were oil prices, at least last week. The WTI price per barrel fell as low as $104 before ending at $108. They reached as high as $122 earlier this month. A shortage of refining capacity, though, is a separate reason why Americans are paying so much at the gas pump. The Biden administration met with oil producers and refiners last week, seeking ways to boost output.

A few notes from Corporate America: FedEx said it’s ready and able to quickly cut capacity if the economy sours. The battle to buy Spirit Airlines continues, with Frontier upping the ante in a bid to curtail a hostile attempt by JetBlue. Citadel Securities became the latest company to move its headquarters out of Illinois, following Caterpillar and Boeing. Chevron, for its part, is moving more of its operations from California to Texas. CarMax, the auto dealer, spoke of growing demand uncertainty tied to higher borrowing costs, vehicle affordability and overall inflation. Kellogg’s, best known for breakfast cereals like Froot Loops and snacks like Pringles, will split into three separate companies. Carnival, a leading victim of the pandemic, is now seeing strong sales for “close-to-home” cruises, buttressed by “tremendous pent-up demand.” Netflix, a leading beneficiary of the pandemic, is now laying off workers. The large Minneapolis-based adhesives manufacturer H.B. Fuller expressed the sentiment of many American companies right now: “Looking ahead, our planning assumptions and guidance are built on an expectation that demand will weaken, although we have yet to see signs of any meaningful slowdown in our underlying demand from customers.”

The latest read from purchasing managers, as surveyed by S&P Global, shows slowing momentum in manufacturing output: “Weaker demand conditions, often linked to the rising cost of living and falling confidence, led to the first contraction in new orders since July 2020.” The report also noted a sharp drop in exports as a strong U.S. dollar makes American products more expensive abroad.

We’ve almost reached the halfway point of 2022. It’s been quite an adventurous first half for the U.S. economy, characterized chiefly by ongoing supply-side difficulties but solid if somewhat softening demand. A first-quarter GDP contraction surprised many, though its true representation of the economy’s health is suspect. A shrinking economy, after all, isn’t typically associated with an unemployment rate below 4%. If there was a single defining characteristic of the year’s first half, however, it was the scourge of inflation, and the Fed’s determined effort to defeat it. This entailed a sharp reversal in monetary policy, headlined by three consecutive interest rate hikes, each one greater than the last. Markets reacted forcefully—stocks plummeted, borrowing costs spiked (especially for home mortgages) and speculative Covid-era excesses imploded (crypto-coins, NFTs, SPACs, meme stocks, electric vehicle IPOs and stay-at-home beneficiaries like Peloton, a latter-day Pets.com). Any list of top developments in the first half of the year, of course, must include what happened in the oil market, with prices racing from below zero early in the pandemic to well above $100 currently. That alone is cause for alarm, and concern that the second half of 2022 might be even more turbulent than the first.

Companies

· Lennar and KB Home: Two of the country’s largest homebuilders reported earnings last week, providing an update on the state of the always-crucial housing market. Their general sense was that it’s cooling in response to sharply higher mortgage rates and pressure on household finances from consumer price inflation. But “while the market has cooled,” said Lennar, “it has clearly not stopped.” Demand, it explained, “remains reasonably strong,” supported by rising household formation. Home prices, to be sure, remain high on a y/y basis. And “supply remains limited across the country,” with the need for affordable workforce housing at “crisis levels.” Indeed, “production of dwellings over the past decade has lagged prior decades by as many as 5m homes.” Lennar detailed which specific markets continue to be strong, namely Florida, New Jersey, Maryland, Charlotte, Indianapolis, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, Phoenix, San Diego, Orange County and the Inland Empire (the latter three in California). “All of these markets are benefiting from extremely low inventory, and many are benefiting from a strong local economy, employment growth and in-migration.” Seeing more of a slowdown are Atlanta, Colorado, Charleston, Myrtle Beach, Nashville, Philadelphia, Virginia, the San Francisco Bay Area, Reno and Salt Lake City. “While inventory is limited in each of these markets, we’ve had to offer more aggressive financing programs and targeted price reductions.” Finally, there’s more “significant market softening and correction” underway in Raleigh-Durham, Minnesota, Austin, Los Angeles, California’s Central Valley, Sacramento and Seattle.

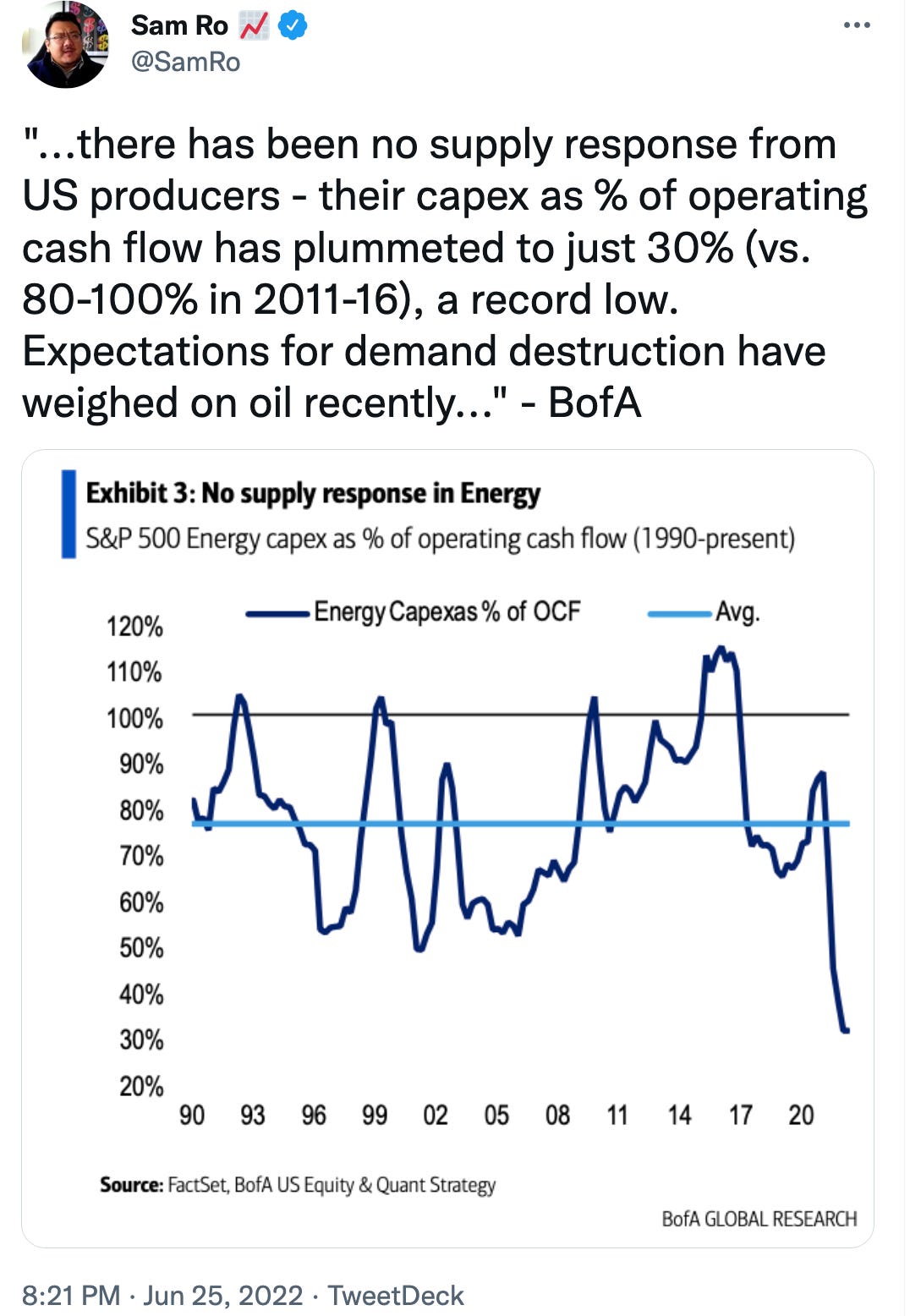

Tweet of the Week

Sectors

· Software: Tech and venture fund billionaire Marc Andreessen, a recent guest on the Econ Talk podcast, highlighted one of the most important realities about the modern U.S. economy—that software really has eaten the world, to use his phrase, but in some sectors much more than others. By just typing into a keyboard, he marvels, things suddenly change in the real world, like when using an app to hail an Uber, or ordering something on Amazon. But while software has brought dramatic change to media, entertainment, communications, advertising and retail, it’s done much less for health care, education, housing, government administration and law. Unfortunately, these categories—where software hasn’t done much to boost productivity—account for the lion’s share of U.S. GDP. These categories, furthermore, are heavily influenced by supply distortions and demand distortions alike. On the supply side, Andreesen mentions “monopolized cartels” like the system that credentials universities. And with respect to demand, the federal government subsidizes or insures home mortgages, student loans and health care. Rana Foroohar of the Financial Times made a related point on the Ezra Klein podcast, warning that just because consumer prices have dropped for four decades, not everything was fine. “The problem is that a cheaper TV doesn’t make up for the fact that all the things that make us middle class—education, health care, housing—are rising at multiple times core inflation rates for decades now.”

· The Prison Economy: If Kentucky were its own country, writes Judah Schept, it would have the seventh highest incarceration rate in the world. Schept is the author of “Coal, Cages, Crisis: The Rise of the Prison Economy in Central Appalachia.” Speaking on the New Books Network podcast, he explains how rural communities have turned to prisons as an economic development tool in the wake of lost coal mining jobs. At its height around 1950, coal mining employed more than 70,000 Kentuckians. Today, the number is more like 3,000, the lowest it’s been since the 1890s. In Eastern Kentucky alone, there are eight prisons (not counting local jails), most of them built in the 1990s and 2000s. Prison jobs statewide amount to about 6,500 today, which is more than double what coal miners employ but still a shadow of coal employment during its heyday. By building more prisons, local communities in central Appalachia also qualify for more state and federal dollars directed to roads, water projects, health care facilities, and so on.

Government

· Defense: In April, the Brookings Institution hosted a talk on defense spending in the U.S., and how it affects local economies. Though spending could reach nearly $850b next year, that would still be just 3.5% or so of total U.S. GDP. That compares to 9% of GDP at the height of the Vietnam War during the 1960s, and 7% during President Reagan’s Cold War arms buildup in the early 1980s. A sizeable portion of federal money for defense is spent at bases, including Fort Bragg as described in the “Places” section below. Other giant bases include Fort Hood north of Austin, Fort Campbell northwest of Nashville, the Lewis-McChord base south of Seattle and Fort Benning near Columbus, Georgia. Naval yards like those in Connecticut and coastal Virginia get a lot of defense dollars as well. Of the money not spent for salaries and health care for military personnel, much goes to contractors led by Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, Boeing and Raytheon. As panelist John Ferrari explained, the U.S. Army, Navy and Air Force are actually shrinking even as the defense budget increases. That increase is mostly because of nuclear weapons modernization, and also because of inflation. There’s also a shift underway from spending on procurement to spending on research and development, with lots of defense-relevant innovation happening outside of the defense sector (at Silicon Valley tech firms, for example). There’s been a big increase in military construction spending, for building shipyards, barracks, depots and arsenals, etc. Waste and inefficiency are undoubtedly issues. So is difficulty recruiting new soldiers and sailors in the current job market. Texas, by the way, is now the number one state for federal defense spending, in part because of its contracts related to the F-35 jet program. As a percentage of state GDP, Virginia ranks first at 11% (it’s home to both the Pentagon and the Norfolk Navy base), followed by Hawaii (9%), Connecticut (8%) and Maryland (7%). Oregon is at the opposite end with only 0.7% of its GDP liked to defense dollars from Washington.

Places

· Cumberland County, North Carolina: When you’ve got an emergency, call 9-1-1. When the President of the United States has an emergency, he calls 9-1-0. That’s the area code for Fayetteville, North Carolina, home to the U.S. military’s XVIII Airborne Corps, along with the 82nd Airborne Division. At any moment, when duty calls, teams of highly trained soldiers are ready to deploy anywhere on earth within hours, by land, air or sea. They’re based at Fort Bragg, which happens to be the largest military base in the world, housing not just the Airborne Corp but also U.S. Army Special Forces Command—think Green Berets and the Delta Force. Fort Bragg is in fact headquarters for the entire U.S. Army Force. The Air Force has a presence there as well and, all told, some 50,000 active-duty military personnel are stationed at Fort Bragg. Include family members, along with Defense Department officials, military retirees and military contractors, and Fort Bragg’s population reaches something like a quarter of a million people. No wonder why some call it “Pentagon South.” Naturally, the fort shapes the economy of Fayetteville and the surrounding areas of Cumberland County. The federal dollars paying for military wages alone is enough to support service businesses throughout the county, to speak nothing of the area’s 850-plus military contractors. According to the Fayetteville-Cumberland County Economic Development agency, the community benefits from roughly $1.5b to $2b worth of military contracts per year. That makes for less cyclicality. The giant military footprint, furthermore, makes Cumberland the fifth most populous county in North Carolina, itself the ninth most populous state in the U.S. The base first opened in 1918, at the end of World War I. It grew sharply during the subsequent World War, followed by the wars in Vietnam and Korea. The pace of growth slowed in later decades. But periodic base realignments mostly resulted in more responsibility for Fort Bragg, not less. A 2005 realignment put Pope Air Force Base within its command. That’s also when the U.S. Army Forces Command and the U.S. Army Reserve Command were relocated there. More recent Pentagon moves have added new units, while concentrating more of the Army’s leadership and special forces there. That has Cumberland County forecasting healthy population increases for the coming decade, having grown about 5% last decade. Unsurprisingly, Cumberland County has more veteran-owned businesses than almost anywhere in the country. But it also has—according to economic development officials—the highest percentage of Black-owned businesses anywhere in the country. Black home ownership is relatively high as well. That’s consistent with the military’s history of being an important force for black economic and social empowerment, dating back to President Truman’s integration of the military after World War II, a move deeply unpopular in much of North Carolina at the time. Today, roughly 40% of Cumberland County’s residents identify as Black or African American. More than 12% identify as Hispanic. And while only 6% are foreign born (compared to 14% nationwide), the area has an international feel given the military’s global responsibilities—there are 85 languages spoken in the local school system, including mother tongues from places like Afghanistan and Iraq where the Army has had extensive deployments. There remains, however, high levels of economic distress around Fayetteville despite all the Pentagon dollars pouring in. The county’s poverty rate is close to 20%, compared to 13% nationally. College attainment is below the national average. The area, to be sure, hasn’t seen the same sort of explosive economic growth taking place in North Carolina metros like Charlotte (with its banking), Raleigh-Durham (with its elite universities and booming IT sector) and Asheville (with its tourism and retirees). But at least it’s adding people, which is more than you can say for about half of North Carolina’s 50 counties. Fort Bragg aside, Cumberland County’s health care and education sectors employ about a quarter of the local workforce. Amazon is building two distribution facilities, lured by Fayetteville’s location along busy Interstate 95, midway between New York and Miami. The Norfolk Southern and CSX railroads run through. The deepwater port of Wilmington is not far. Goodyear Tire, Campbell’s Soup and Cargill are among the manufacturers with production or distribution facilities in the county. Booming Raleigh is about a 1.5-hour’s drive north, close enough for about 4,000 Cumberland residents to commute to jobs there each day (efforts are underway to establish an Amtrak link). The Fayetteville airport, meanwhile, though small, actually gained new flights during the pandemic, a testament to the economy’s relative resilience during the pandemic, aided by the steady flow of Pentagon dollars. To be clear though, the pandemic did hit hard, especially in the service sector. Another challenge for local businesses is competition with the military base, which features its own entertainment and other facilities catering to troops and their families. In addition, the base, along with other big employers like hospitals and colleges, are exempt from taxation, straining local government resources. A challenge for the housing market is the transient nature of military personnel, who often remain at a given base for only a temporary period. On the other hand, a large nearby military base implies a young demographic overall, and many retirees with unique skills. Robert Van Geons, President and CEO of Fayetteville-Cumberland County Economic Development, is leading the charge to recruit more residents and businesses to the area. Golfing and nearby parks help with attracting retirees—the mild winter weather doesn’t hurt either. Efforts are underway to improve broadband infrastructure. Downtown Fayetteville is seeing more investment. Crypto mining, notwithstanding the sector’s current troubles, is prevalent in the county. It’s the Pentagon though, that dominates the economy. (Sources: Fayetteville-Cumberland County Economic Development, HUD, U.S. Census, Department of Defense, US Army).

· Corpus Christi: Los Angeles and Long Beach in southern California constitute America’s busiest container port complex. It’s not even close. But that’s just containers. Looking at overall revenue tonnage for all goods and commodities shipped, the nation’s busiest port (in 2020) was in Corpus Christi, Texas. Why is it so busy? In large part because of energy shipments. In 2015, the U.S. lifted its ban on exporting crude oil, much of which has since flowed out of Corpus Christi. The city, located along the Gulf of Mexico, separately attracts a lot of tourists to its beaches. There’s a Naval Station and Army Depot there as well.

Abroad

· Foxconn: A recent episode of the Bloomberg “OddLots” podcast talked about the Taiwanese company Hon Hai, better known as Foxconn. It’s one of the most important companies in the world as far as the U.S. economy is concerned, second perhaps only to Taiwan’s semicon powerhouse TSMC. “If Foxconn or TSMC were to disappear from the face of the earth overnight,” said Bloomberg Opinion columnist Tim Culpan, “we’d be in a lot of trouble because nobody can do what these companies can do.” Host Joe Weisenthal adds: “It’s hard to understand the world over the last decades without understanding the trajectory of Foxconn.” The company was founded in the mid-1970s by entrepreneur Terry Goh, one of the first to recognize the potential of manufacturing in China—Shenzhen more specifically—with its huge pools of cheap labor. Goh began producing low-cost plastic items and moved into connector cables linking, for example, PCs to printers. The “conn” in Foxconn refers to these connectors. Next came components for personal computers, winning clients like Dell and HP in the U.S.—this was the 1990s, when American firms began outsourcing production to Asia. One of these firms was Apple, which was producing its Mac computers in California at the time. When returning CEO Steve Jobs and his chief operating officer Tim Cook were ready to produce the iPod, however, Apple too was looking to Asia. Foxconn would be its key iPod supplier, later providing components and assembly for iPhones and iPads. By 2010, Foxconn had about 1m employees, many working on Apple products. Even today, 70% of all Apple iPhones are made by Foxconn, creating a mutual dependence—an “unhealthy co-dependence,” Culpan suggests. About half of Foxconn’s $215b in annual revenue comes from Apple. Now, the Taiwanese company wants to enter the electric vehicle space, hoping to turn EVs into something like PCs on wheels.

Looking Back

· Container Ships: A Wall Street Journal article about the Russian military’s use of railroads featured a reference to the U.S. military’s use of container ships during the Vietnam War. In 1965, a buildup of U.S. troops in the Asian nation came with the challenge of having to supply all those troops. “Supplies piled up on the shores of the embattled country, and ships were waiting weeks to unload.” Along came American shipping entrepreneur Malcolm McLean, who had led development of the standardized shipping container almost a decade earlier. As the article explains, McLean persuaded the Defense Department to adopt his innovation, risking his own money to build a container terminal at Cam Ranh Bay. Said Marc Levinson, author of “The Box”: “In pretty short order, containers solved the military’s problems. It really transformed the ability to fight the war.” It also sparked demand for use of containers in the private sector, revolutionizing world trade by dramatically lowering costs. Containerization, as “The Box” recounts, also revolutionized urban economies, wiping out the labor-intensive dockworker trade in cities like New York and San Francisco. Indeed, the loss of huge numbers of low-wage dockworker jobs was a major reason for New York’s financial troubles in the 1970s. Before container ports, linked to highways and rail lines, most factories needed to be close to the seaport, which is why so many of them were in New York City. In 1964, according to Levinson, the city’s five boroughs were home to some 30,000 factories employing 900,000 workers. But between 1967 and 1976, New York lost a fourth of its factories and a third of its manufacturing jobs. The shipping container is not entirely to blame, of course. Nor was it the only reason for the port’s demise—it also suffered from aging docks, labor strife, corruption, the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway and the shift of America’s industrial base away from places like Buffalo to places in the Sun Belt.

Looking Ahead

· Carbon Removal: Getting off fossil fuels is proving more difficult than some imagined. Despite untold billions in research into alternatives, it’s still hard to beat the economics of oil and natural gas when it comes to making everyday fuels and products that power the modern economy. The effort, however, continues. A recent Wall Street Journal article looked at one potential solution to climate change that doesn’t involve a substitution for fossil fuels, but rather a means to remove carbon pollutants from the air and store them permanently underground. As the Journal describes, some are calling carbon removal technology the “hottest sector in climate finance.” Indeed, billions in commitments are pouring in, “turning carbon removal into a hotbed of technical and financial innovation.” Google and Meta are among firms that have promised to purchase energy whose emissions are removed from the atmosphere, creating a big incentive to devise technology that works. The idea borrows from vaccine development, where companies that produce a successful one are rewarded heavily with guaranteed sales. Carbon removal is distinct from carbon capture, which involves grabbing the carbon not from the air but at the site of its production, i.e., a factory smokestack. Carbon removal is tougher because the pollutants are dispersed throughout the atmosphere. It’s also at this stage still an immature and cost-prohibitive process. Occidental Petroleum has one of the most ambitious carbon-removal plans, with an intent to spend up to $1b on a direct-air-capture facility with Canadian startup Carbon Engineering. The facility would bury some of the carbon underground and use some to produce oil. Airbus agreed to purchase carbon credits linked to the project, and United Airlines is among its investors.

· Geoengineering: Looking for ideas even bolder and more speculative than carbon removal? One is an attempt to cool the earth by reflecting more sunlight back to space. It’s called geoengineering. A website called “Futurism,” meanwhile, ran this headline last week: “MIT Scientists Want to Put a Barrier Between Earth and Sun to Fight Climate Change.” Included was a sub-headline: “What, Like You Have a Better Idea?”